Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

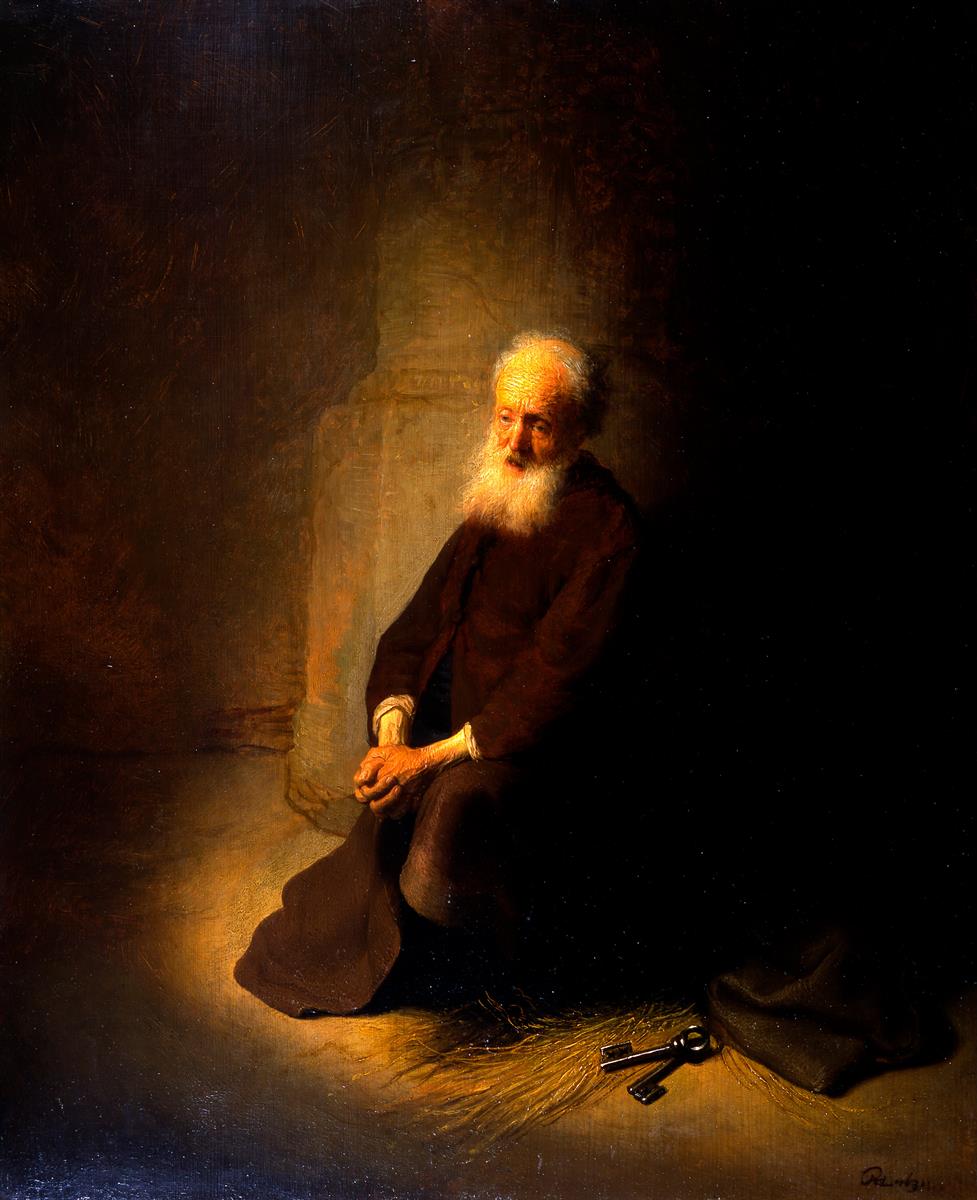

Rembrandt’s “St. Peter in Prison” (1631) is a dramatic meditation on conscience and grace staged with the fewest possible means. In a sparse cell, an elderly man sits at the edge of a straw-covered floor, hands bound in thought rather than iron, beard and brow illuminated by a raking light that leaves most of the room to darkness. A bundle of keys glints near his feet like a quiet declaration of identity, and the outside world is excluded by stone. The picture is not about spectacle or miraculous escape. It is about the interior moment when a life takes stock: the weight of failure, the stubbornness of hope, and the transformation of fear into trust.

Historical Context And Rembrandt’s Early Mastery

The painting belongs to Rembrandt’s ambitious early Amsterdam period, when the young artist—fresh from Leiden—was testing how selective illumination could carry narrative and psychology. In the late 1620s and early 1630s, he made small panels and copper paintings that compress history into a single, telling moment. “St. Peter in Prison” is one of these concentrated dramas. It shows a painter still fascinated by the theatrical possibilities of chiaroscuro yet already moving toward a more humane, introspective storytelling. The theme gives him a perfect instrument: a saint whose story is defined by boldness and denial, by chains and release, by tears and commission.

The Subject And The Theology Of Aftermath

Tradition recounts Peter’s imprisonment after preaching in Jerusalem and later under Herod; the Acts of the Apostles tells of an angelic release. Rembrandt chooses not the miracle itself but the pause before or after it—the interior interval when Peter measures himself. The figure’s posture is not defiant; it is reflective. The clasped hands, the lowered head turned into the light, the slight forward cant of the body suggest prayer, regret, or the gathering of courage. The keys at his feet—iconographic shorthand for the “keys of the kingdom” entrusted to Peter—lie outside his hands, as if to say that authority remains true even when the man who bears it feels small. The scene is aftermath rather than event: the soul’s weather after the storm of failure and before the clarity of vocation.

Composition As Architecture Of Silence

Rembrandt organizes the pictorial space like a stage emptied for a soliloquy. The figure occupies the lower right quadrant, seated near the front edge so that our viewpoint feels intimate, almost on the straw with him. The stone pier at the back left rises like a mute witness, its mass counterbalancing the man’s slight frame. A dark wedge of shadow occupies the right two-thirds of the painting, pressing the figure toward the lighted patch of floor. This triangular fight between light and dark is the compositional engine: a force that pushes Peter outward while the night pushes back. Nothing in the room distracts—no shackles on the wall, no window bars, no guard. The emptiness is purposeful. It makes the cell a chamber for decision.

Light As Moral Speech

The light does the storytelling. It enters obliquely from the left, washes the man’s forehead and beard, kisses the cuffs of his sleeves, and spreads across the straw like a path of mercy. The rest of the environment is encased in darkness so deep that it feels almost thick, a substance rather than an absence. This dramatic chiaroscuro is not pyrotechnic display; it is moral rhetoric. Light behaves as recognition, even as pardon. It acknowledges the frailty of the sitter and gives him visibility at the very moment he might wish to hide. The light’s angle also shapes the figure’s psychology: by striking Peter’s temple and cheek, it makes the head a lantern of thought, and by leaving the eyes in delicate half-tone, it spares the moment from theatrical self-exposure.

Palette, Temperature, And Tonal Music

Rembrandt’s color vocabulary here is a subtle orchestra of earths. Warm browns and umbers ground the cell; a resinous red-brown builds the robe; pale, leaden whites skim sleeves and forehead; the straw is a cluster of ochers and yellow lakes that break into sparks where the brush lifts. The overall chroma is low, but temperature shifts carry emotion. Warmth gathers around the head and hands; cooler grays inch along the stone; a nearly black brown sits behind the figure like the pressure of worry. Because the palette is restrained, each note matters. The small blue-cool shadow under the beard, the greenish whisper near the keys, and the honeyed rim of light along the floor all contribute to the mood of held breath.

The Keys And The Grammar Of Symbol

Peter’s emblem appears without fanfare: two large keys lying on the straw near his robe. They shine enough to be legible but refuse ostentation. Their placement beside rather than within the saint’s hands is eloquent. Authority is his, but it is not the subject of his attention. In the narrative arc of Peter’s life—fisherman, disciple, denier, and cornerstone—the keys are promise more than prize, vocation more than possession. Rembrandt treats them as such: tangible, weighty, quiet. They anchor the corner of the composition and balance the bright triangle of straw, giving the lower half visual and symbolic gravity.

Gesture And Psychological Truth

The body carries the interior monologue. Peter’s shoulders round forward, a posture that shows age and humility without caricature. The hands interlace, not tightly but with the soft pressure of someone who has prayed long enough to soften muscle memory into habit. The head turns into the light—not as if startled, but as if sought. Rembrandt avoids the heroic gaze or the dramatic collapse. Instead, he records a believable man in the moment of self-scrutiny. The decision to seat the figure rather than show him standing with fetters is crucial. A seated body takes on the scale of thought; it becomes an instrument of inwardness.

Matter And The Intelligence Of Paint

Up close, the pictorial surface reveals the young Rembrandt’s fearless handling. The beard is built with lifted, sticky strokes that catch real light; the cuffs are small ridges of opaque paint that sparkle against the robe; the straw is a scratchy calligraphy of short, thin lines over a mid-tone, animated by occasional bright nicks. The stone is not finely described; it is a haze of scumbles through which earlier browns breathe, establishing atmosphere rather than masonry. The robe’s broad planes are knitted from slightly different browns, some thinned with medium to translucence, others fat and leathery. This play of thickness and thinness allows the painting to stage its drama physically: thick where attention and grace land, thin where darkness needs to breathe.

Space, Silence, And The Poetics Of The Indeterminate

The cell is indeterminate by design. A pale column and a suggestion of floor are all we have for architecture. There is no door or barred window; there is only an edge where light surrenders to dark. That edge functions like the threshold of conscience. The painting therefore moves the prison from geography to interiority. Peter’s solitude is not literal isolation—he will be led out, as the story promises—but the solitude of reckoning. By refusing descriptive clutter, Rembrandt places the viewer in the same silence. We inhabit the interval between failure and forgiveness, between mandate and the courage to accept it.

Iconography Of Age And Vocation

Rembrandt, throughout his career, painted age with tenderness. In this early work he already knows how to register years without brutality. The dome of Peter’s skull gleams; the skin along the cheek collapses just enough to suggest time and fasting; the hands display both strength and tremor. The robe is monkish, brown and unadorned, making the saint a brother to every penitent rather than a credentialed dignitary. Age here is not spectacle but authority: the kind earned by endurance and softened by mercy. The image proposes that vocation matures in such silence, that leadership is born not from pride but from the long rehearsal of humility.

Theological Reading Without Preaching

The painting invites theological reflection without corralling the viewer into a single interpretation. For a Christian viewer, the light can read as grace and the keys as apostolic authority recovered after failure; for a general viewer, the elements may speak about conscience, responsibility, and the strange way dignity reappears after regret. Rembrandt provides symbols but lets them remain negotiable, turning the scene into a humane parable rather than a doctrinal diagram. The painting’s generosity lies in that openness: it trusts the viewer to finish the thought.

Comparisons To Other Early Rembrandt Nocturnes

“St. Peter in Prison” belongs with Rembrandt’s early scenes of quiet crisis: “Judas Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver,” “The Apostle Paul,” and intimate biblical moments staged in dim rooms with a single light source. Those works share the same ethical stance: a refusal to exploit extreme emotion for show, and a willingness to trust a face, two hands, and a piece of furniture to carry epic meaning. This painting is perhaps the most distilled of the group. It eliminates furniture and retains only straw, stone, man, and keys. The result is almost modern in its minimalism and striking in its empathy.

Technique, Layers, And The Time Kept In The Surface

The sequence of making can be read in the panel’s stratigraphy. Rembrandt appears to have laid a warm ground, over which he mapped the large shadow shapes. He then built the figure in middle values, reserving lights for last. Flesh passages were developed with semi-opaque mixtures that allowed undercolor to glow, then complicated with cool and warm half-tones to give breath. Highlights were struck late on the forehead, beard, cuffs, and keys, while the straw was sharpened with thin, quick strokes scratched into the still-tacky paint. Slight pentimenti along the robe’s hem and the edges of the hands suggest revisions as he sought the right tilt and pressure. The work bears the time of its making in a way that deepens the time of its story—days in prison, hours of thinking, seconds of recognition.

The Viewer’s Choreography

Rembrandt engineers a path for the eye that mirrors the saint’s inner movement. Most viewers enter the image at the brightest point—the forehead and beard—then travel down the angle of the head to the interlaced hands, then to the straw’s bright triangle and the keys nestled in it. From there the gaze circles back along the shadowed hem of the robe to the illuminated cuffs and returns to the face. This loop repeats the pattern of thought: from mind to responsibility, from responsibility to calling, from calling back to mind. The experience of looking becomes a small exercise in contemplation.

The Ethics Of Attention

One of the painting’s lasting achievements is its ethic of attention. Rembrandt gives the full dignity of careful seeing to a scene that could easily have been melodramatic. He neither amplifies misery nor softens age; he allows the saint to simply be—a man in a room, thinking. That attentiveness is a model for viewers. The portrait suggests that moral life depends less on spectacle than on such unobserved moments. The painting’s quiet insists that looking itself can be a form of respect and that respect is the beginning of understanding.

Resonance For Contemporary Audiences

Although the story is biblical, the emotion is contemporary. Many viewers recognize the cell of reflection: the night after a failure, the pause before a hard choice, the loneliness of leadership. The image offers no quick exit, only the reassurance that light finds the face that turns toward it and that vocation remains near even when one’s hands rest empty. The keys glint at the edge of the light like possibilities that do not vanish just because one is tired. This blend of realism and hope explains why the painting continues to feel fresh: it honors human limitation without capitulating to it.

Conclusion

“St. Peter in Prison” is an early triumph of Rembrandt’s narrative intelligence. With stone, straw, keys, and an old man in a robe, he builds a theater for conscience in which light plays the part of mercy. The composition concentrates emotion without forcing it; the palette sings low and true; the brushwork turns paint into beard, sleeve, and breath. Above all, the painting trusts the viewer to recognize the drama of a soul facing itself and to understand that such facing is where freedom begins. The miracle of deliverance is implied, but the miracle of attention is shown. In the quiet glow of this cell, Rembrandt teaches that the deepest transformations begin in silence.