Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

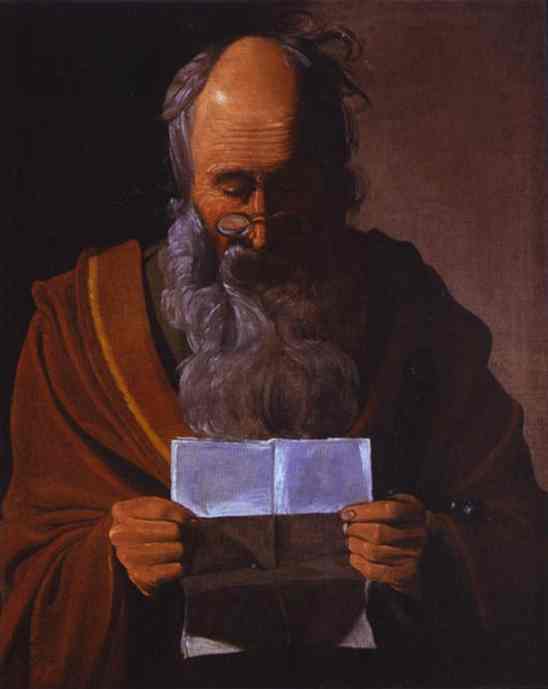

Georges de la Tour’s “St. Paul” (1620) captures the apostle at half-length, withdrawn into a chamber of warm shadow where a single, disciplined light models flesh, cloth, and steel. The saint’s head bows slightly; the beard gathers like a dark river across the chest; one hand steadies a large book while the other rests near the hilt or blade of a sword—the two attributes that have identified Paul for centuries. Nothing distracts from this dialogue among mind, text, and instrument. De la Tour, already in his early period, has found the grammar that will define his career: a pared stage, a sovereign source of light, and a moral seriousness that honors ordinary material as the bearer of sacred meaning.

Composition and the Architecture of Thought

The composition organizes itself around a calm diagonal that runs from the saint’s forehead through the nose and down to the open or thickly bound book. A second counter-diagonal rises from the sword toward the shoulder and beard, intersecting just under the sternum. At that crossing, Paul’s interior life becomes visible. The book anchors the lower right or lower left quadrant as a pale plane, while the sword introduces a narrow vertical that steadies the mass of the body. De la Tour crops the figure tightly, trimming away anecdotal space so that hands, face, book, and sword comprise the whole world. The effect is monumental intimacy: the viewer stands close enough to feel the paper’s edge and sense the weight of iron but remains outside the apostle’s inward orbit.

Light as Spiritual Measure

Illumination enters from high at one side and lays a path across the brow, cheek, hand, paper, and metal. This light is not theatrical. It is a disciplined weather that reveals what matters and lets the rest recede. The brow receives a broad, matte glow, implying intelligence at work; the book’s leaf flares in a controlled whiteness, promising legibility; the sword catches a clean highlight along its ridge that feels like a line of doctrine drawn through air. Shadows thicken beneath the beard and along the sleeve, not as menace but as reserve. De la Tour’s chiaroscuro is an ethics of visibility: revelation belongs to what is needed for understanding and obedience, while mystery protects what should remain quiet.

The Book and the Work of Writing

If any object dominates beyond the body, it is the book. Paul is not only a missionary and martyr; he is a writer whose letters shaped the foundations of Christian thought. De la Tour renders the volume with affectionate accuracy: a heavy board cover, a curl at the corner of a page, a mass whose weight we feel in the resting hand. The surface of the leaf is articulated in sober bands, suggesting lines of text without distracting with legibility. The book becomes the painting’s bright floor, a field on which the saint’s mind stands. Its nearness to the hands signals craft. Writing for Paul is not remote inspiration; it is labor, revision, the friction of finger and page.

The Sword and the Edge of Doctrine

The sword is the classic attribute of St. Paul, both as the instrument of his martyrdom and as an emblem of the “sword of the Spirit”—the incisive power of the Word. De la Tour refuses ornament. He gives a plain blade or hilt whose polished facets catch a few quiet lights. The metal’s edge is not gore-stained or heroic; it is functional and exact. In the composition the sword’s vertical corrects the softness of beard and cloth, introducing a rectitude that balances compassion with clarity. The object therefore reads on three levels at once: historical, theological, and formal. It remembers the end of Paul’s life, signifies the keenness of his teaching, and gives the design its necessary line.

The Hands and the Ethics of Touch

De la Tour always tells truth with hands. Paul’s fingers do not clutch the book nervously, nor do they splay in proclamation. They rest with a practiced weight, strong from travel and work, calm from thought. The other hand—near the sword—neither flaunts nor hides. It acknowledges the instrument with a craftsman’s economy. Knuckles gleam where the light lands; veins rise modestly; nails are clean but not precious. These hands convince the viewer that the intelligence visible in the brow belongs to a body that has carried burdens, sewn tents, and endured. The saint’s authority is articulated in the balance between grip and gentleness.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The palette is sober and warm: earth umbers, olive blacks, burnished reds, the chalk of paper, and the muted silver of steel. If a mantle of red or russet crosses Paul’s shoulder, it does not blaze; it breathes, turning from ember to shadow as folds swing from light. Flesh is built from honeyed ochres that cool into brown where form turns away. The book’s page is the brightest field, yet even its whiteness is warmed by the ambient tone, preventing any icy glare. This restrained harmony keeps emotion steady. The color is pious and human, free of decorative vanity. It sets the mind for reading.

Surface and Painterly Method

Nothing in the surface shouts. De la Tour fuses strokes into large planes, then refines edges where light meets form. Beard and hair are handled as soft, granular fields; skin is a matte amalgam of warm and cool notes; the sword’s highlight is a single clear lane; the page’s edge is a decisive lip. The painter’s discipline mirrors the saint’s. Flourish would spoil the prayer. Instead, craftsmanship serves concentration, producing a tactile world—paper that almost squeaks under the thumb, metal that yields a cold reflection, cloth that absorbs silence.

Space, Background, and the Chamber of Attention

The background is a hushed field: a recession of brown toward black on one side, or a lean wall on the other that catches just enough light to push the figure forward. There are no columns, landscapes, or trophies. The room is not a stage but a chamber of attention. In such a space the smallest event becomes significant: a page about to be turned, a finger marking a passage, the faint glimmer along a blade. By refusing scenery, de la Tour allows the viewer’s eye to practice the same discipline the saint’s mind is practicing.

Psychology and the Turn of the Head

Paul’s head inclines toward the book even as the gaze may drift a degree off the page. The posture suggests the mind in motion—remembering a verse, composing a sentence, weighing a doctrine. The mouth is closed, the jaw set without strain. Eyes partly submerged in shadow avoid spectacle and invite empathy. We do not “catch” Paul delivering a sermon; we meet him in the private labor that makes preaching truthful. In this inwardness lies the painting’s distinctive power. It gives the public apostle back his study, and by doing so, dignifies study itself.

Iconography and the Balance of Roles

De la Tour’s iconography is concise but complete. The book recalls the letters; the sword anticipates martyrdom and symbolizes the Word; the mantle evokes dignity; the severe light speaks of conversion, that lightning of insight on the road to Damascus where persecutor became apostle. Without depicting the horse or the fall, the painting carries that story in its moral weather. The saint is a man forever oriented by a beam that struck him once and keeps striking him in memory, now translated into the steady light by which he reads.

Dialogue with Caravaggesque Traditions

Painted around 1620, the picture participates in a European current that prized directional light, half-length figures, and realism of texture. De la Tour absorbs those lessons but refuses their common melodrama. Where a more flamboyant Caravaggesque might rake the face with violent contrast and sharpen the sword into an emblem of menace, de la Tour tempers everything into a meditative climate. His chiaroscuro is not a spotlight; it is a climate conducive to thought. The result is a kind of northern classicism: truthful, dignified, and spare.

Relation to the Apostle Series

“St. Paul” belongs to an early cluster of apostolic images—St. Andrew bending over a book, St. James the Greater outfitted for pilgrimage, St. James the Minor gripping a worker’s club. Within that set, Paul is the thinker with an edge. Andrew’s page turns; James’s staff steadies; Paul’s sword clarifies. The series demonstrates how de la Tour derives character from attribute and gesture while maintaining a shared discipline of light and reduction. Seen together, the apostles form a quiet manifesto about the varieties of vocation and the unity of interior life.

Theological Reading of Book and Blade

The pairing of book and sword is not simply additive; it proposes a theology. Scripture without discernment can become rote; a cutting word without the page’s patient grammar can become cruelty. De la Tour binds the two. The blade gleams only because the page’s whiteness throws light; the page holds the eye only because the blade’s line promises incision. In Paul’s hands, doctrine cuts to heal, and reading becomes obedience. The painting thereby offers a subtle education: it teaches the viewer to want clarity that is charitable and charity that is lucid.

The Viewer’s Position and the Ethics of Witness

We stand close—at the desk edge, almost shoulder to shoulder—yet we do not interrupt. The saint neither looks up nor asks us to confirm him. Our task is to watch without presumption, to let the restrained drama of hand, book, and sword re-order our own attention. De la Tour often recruits the viewer into a practice of looking that resembles prayer. Here, that practice is intellectual devotion: to read slowly, to test the edge of an idea, to consent to what one has seen.

Modern Resonance of a Seventeenth-Century Image

Even for an audience outside the painting’s confessional world, “St. Paul” remains potent because it dignifies concentrated work. The book is the realm of research; the sword is principled decision; the silence is the atmosphere in which both can occur. Anyone who writes, judges, edits, or teaches will recognize the posture. De la Tour’s world of matte surfaces and honest textures restores trust in slow processes. In a culture inclined to spectacle and noise, the painting proposes a different model of authority: patient, learned, and exact.

Material Poetry of Paper, Flesh, Cloth, and Steel

One of the canvas’s quiet pleasures is the way four materials converse. Paper reflects light into flesh; flesh warms the red of cloth; cloth’s shadow cools the steel; steel’s glint returns the eye to the page. This circuit binds the image into a single, breathing organism. The poetry is tactile rather than rhetorical. Nothing is symbolic that is not also real. The book weighs; the sword chills; the cloth insulates; the skin registers the world’s temperature.

Time, Memory, and the Page About to Turn

De la Tour often gives the viewer time in paint. A leaf lifts. A pen pauses. A hand marks a place. In “St. Paul,” that suspended instant carries the weight of a life transformed and then poured out in letters. The page about to turn is the future of doctrine becoming history; the sword held at peace is the cost accepted but not flaunted. The painting therefore feels both still and forward-leaning. It is a pause that prepares motion.

Conclusion

“St. Paul” offers a complete portrait with very little: a head inclined in thought, a book that anchors attention, a sword that edges truth, and a light that decides what deserves to be seen. Georges de la Tour’s early masterpiece shows how a room emptied of ornament can be filled with significance, and how an apostle’s authority can be rendered without thunder—through hands that know their tools, a face that consents to discipline, and objects that mean exactly what they are. The work honors reading as a sacred labor and doctrine as a humane edge. It stands quietly in the tradition of sacred painting while speaking directly to any viewer who has ever had to think carefully before acting.