Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

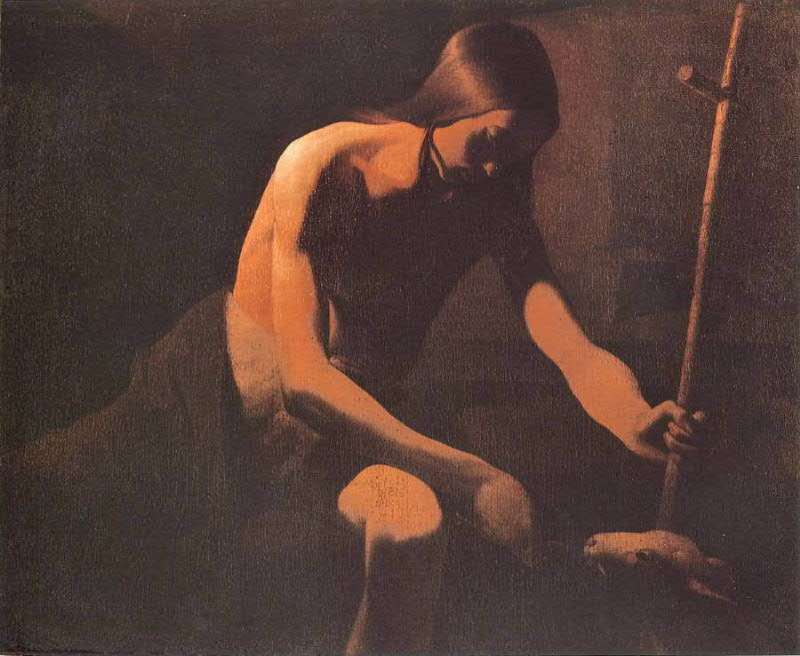

Georges de la Tour’s “St. John the Baptist in the Desert” (1651) is one of the most austere and haunting interpretations of the forerunner of Christ in seventeenth-century art. In a composition stripped to its bones, the saint sits in a pool of coppery darkness, body bent forward, hands quiet, staff planted like a vertical axis in the dusk. The lamb at his feet—small, pale, and nearly abstract—echoes both his message and Christ’s title as the Lamb of God. Rather than dramatizing the wilderness with rocks, plants, and theatrical skies, de la Tour reduces the scene to essential relationships of light, volume, and gesture. The result is a meditative image in which the desert is interior, the prophecy is silent, and holiness is rendered as a steady, self-contained flame.

A Late Work and the Language of Reduction

Painted toward the end of de la Tour’s career, this canvas distills many traits of his late style: pared-down settings, matte surfaces, large planes of color, and an almost geometric control of light. Earlier depictions of saints by the artist include more accessories—books, skulls, ropes, lanterns—yet here nearly everything has been subtracted. That reduction is not an absence of meaning but a method for concentrating it. Each remaining element—the figure, the staff with its cross-arm, the lamb, the swath of cloth around the waist, the wedge of illuminated skin—becomes a syllable in a sentence that reads as prayer.

Composition Built on Diagonal Gravity

The figure of John forms a broad diagonal from the upper left to the lower right, a line reinforced by the tilt of his torso and the reach of his right arm toward the staff. This diagonal is not aggressive; it is gravitational, as if the saint’s thoughts weigh him gently toward the ground. The staff rises as a counter-movement, steadying the composition and converting weight into witness. The small lamb occupies the rightmost base of that vertical, a visual signature that binds the prophetic message—“Behold the Lamb of God”—to the very architecture of the picture.

The Desert as Negative Space

De la Tour refuses the descriptive conventions of wilderness painting. There are no distant horizons, no clumps of scrub or bleached bones. Instead he offers a nearly uniform field of warm darkness that behaves like felt. The “desert” becomes a psychological and spiritual condition: an uncluttered interior where one listens for a voice. This negative space is not laziness; it is a carefully organized silence that allows the smallest inflection of light on skin or wood to carry immense rhetorical force. In this sense, de la Tour anticipates modern minimalism, where subtraction is the key to revelation.

Light Without Flame

Unlike his celebrated candlelit nocturnes, this painting conceals the light source entirely. The illumination seems to flow from the upper left, striking shoulder, arm, and knee, then fading into brown. The effect is reminiscent of late afternoon sun filtered through a cave mouth or a cloth canopy. Because no candle claims our attention, the light feels natural, humble, and unsentimental. It behaves like grace in the theology of the painting: it does not demand notice; it simply enables forms to be themselves.

Flesh as Architecture

De la Tour builds the saint’s body with planar clarity. The lit shoulder is a trapezoid; the upper arm reads as a cylinder; the bent forearm spills into a wedge; the knee is a rounded block. These decisions produce a body that is at once modern—nearly abstract in its simplicity—and sensuously human. The paint is matte and unadorned, emphasizing structure over sheen. This architecture of flesh suggests that asceticism has given John a kind of carved presence, stripped of excess but strong in contour and purpose.

Gesture as Narrative

There is no storytelling in the conventional sense, yet gesture carries a quiet narrative charge. John’s left hand rests open and downward near the knee, a release of will that signals consent rather than struggle. His right hand grips the staff at its base in a clasp that is firm but not clenched. The staff’s cross-arm, small and nearly hidden at the top, makes the object simultaneously a walking aid and a prophetic emblem. The saint’s head inclines, hair falling forward in a curtain, eyes turned toward the ground. Whether we read that angle as compunction, contemplation, or rest, the lesson remains the same: prophecy gathers itself in silence before it speaks.

The Lamb as Echo and Counterform

The lamb is scarcely described: a pale oval head, a hint of back, two tiny ears. Its very minimality allows it to function symbolically without sentimentality. It sits at the foot of the staff like the footnote to a sermon, modest yet essential. The lamb’s soft oval answers the hard vertical of the staff and the angular silhouette of the saint. This counterform keeps the composition from becoming austere to the point of severity, adding a touch of vulnerability that humanizes the whole.

Color as Moral Temperature

The palette hums in a narrow band: umbers, siennas, and quiet flesh tones. There is no blue, no crisp white, no decorative contrast. Color thus becomes moral temperature rather than ornament. Warmth concentrates on the skin where the light touches; the garment and background soak up the glow in brown. The effect is of a world in which only what matters animates itself—the human body called to vocation—while everything else recedes in respectful hush.

Caravaggist Roots and De la Tour’s Difference

De la Tour’s art is often aligned with Caravaggism for its dramatic light and devotion to ordinary models. The kinship is real, yet this painting reveals crucial differences. Caravaggio often stages conversion as instantaneous shock, with light crashing onto figures amid theatrical gestures. De la Tour’s conversion is slow, sedimentary, quiet. Light here caresses rather than slashes; hands negotiate rest rather than conflict; the environment does not crowd the subject. The drama is interior and long-lived, an asceticism of form that matches John’s spiritual regimen.

The Staff as Cross and Compass

The staff carries multiple functions. Practically, it is the traveler’s aid that kept the desert wanderer upright. Iconographically, the small transverse bar marks it as a cross-staff, anticipating the Crucifixion and identifying John’s message with Christ’s destiny. Compositionally, it stabilizes the diagonals and gives the eye a vertical to climb. Psychologically, the staff is something to hold—a companion that turns loneliness into pilgrimage. De la Tour allows all these meanings to coexist without insisting on any single one, trusting the viewer to hold them as the saint holds the wood.

The Hair as Veil

John’s long hair falls forward like a veil, obscuring his eyes. That concealment is crucial to the painting’s mood. It denies easy portraiture and turns the head into a sign of inwardness. We do not read expression in an exposed face; we read it in the body’s orientation and the temperature of the light. The saint’s anonymity underscores the idea that the desert erases the ego in order to prepare a voice. In that sense, the hair hovering between viewer and face functions like the Prophet’s silence before speech.

Tactility and the Ethics of Surface

The paint surface is modest and tactile. One senses the drag of the brush on a slightly absorbent ground, the way pigments settle into the canvas weave. This humility of surface answers the humility of subject. By refusing glossy effects, de la Tour aligns the painting’s material with John’s message of repentance, suggesting that truth prefers rough fabric to polished display. Even the lamb is matte, absorbing light rather than reflecting it, as if the whole scene were wrapped in a spiritual felt.

The Desert as Workshop of Attention

In this work the desert is not a place to escape the world but the workshop where attention is trained. The saint’s posture is a lesson in attention: head bowed to reduce the horizon, body anchored to limit distraction, hand steady on the staff to keep the mind from wandering. De la Tour translates those habits into pictorial decisions. The frame denies us extraneous detail; tonal restraint keeps the eye from skittering; the light’s steady fall slows our looking. By the time we have considered these relationships, we have already practiced the very discipline the painting honors.

Vanitas in Discretion

Late Baroque painters often stock their ascetic saints with skulls, hourglasses, rotting fruit—overt reminders that life is brief. De la Tour refuses such signals here. Mortality is present but discreet: in the thinness of the saint’s body, in the lamb’s vulnerability, in the brown atmosphere that could be evening. Instead of preaching, the picture allows us to feel time passing as light slides off skin into shadow. The absence of props grants the viewer a more capacious meditation already tuned to the quiet.

An Anatomy of Silence

Silence is not emptiness; it has shape. In this painting silence is articulated by the long arc of the back, the parallel lines of forearm and thigh, the still triangle formed by shoulder, chest, and bent knee. These shapes form a grammar we understand without words. The saint is not doing; he is being. That ontological emphasis is a hallmark of de la Tour’s mature art, which prefers states to actions, essences to episodes.

Dialogue with Earlier Baptist Images

When compared to the high Renaissance and Mannerist versions of John—muscular youths pointing theatrically toward heaven in bright landscapes—de la Tour’s Baptist looks dematerialized and intent. The index finger that so often directs a viewer’s gaze is conspicuously absent. Instead of pointing away, he gathers inward. This change shifts the theological emphasis from spectacle to interiority and from announcement to preparation. The prophet becomes the prototype of contemplative mission: one speaks truly only after long listening.

The Viewer’s Position

De la Tour places us close to the figure, slightly below the shoulder line, as if we entered the cave at dusk and halted in respect. Because the saint’s gaze is hidden, we are not compelled into dialogue; we are invited to companionship. The staff, planted near the painting’s edge, becomes a barrier we will not cross. The lamb, however, sits on our side of that barrier, a gentle ambassador that draws us into the sphere of meaning without violating the saint’s privacy.

Technique and the Discipline of Edges

Edges in this canvas are handled with law-like consistency. Where light meets form, the edge is precise; where form dissolves into darkness, it softens. This discipline creates a breathing rhythm across the surface. Highlights on shoulder and forearm are crisp enough to read as bone under skin; the transition around the back and garment melts into a gentle fade. Such edge control keeps the composition legible even at great simplicity, and it underscores the painting’s commitment to clarity without clamor.

Historical Weather and the Afterlife of the Image

Composed in 1651, the work arises from Lorraine’s recovery after decades of war. The atmosphere of rebuilding through quiet fidelity pervades de la Tour’s late oeuvre. “St. John the Baptist in the Desert” carries that ethos into sacred portraiture. It proposes patience as the foundational virtue of renewal. The painting’s influence ripples forward to artists who explored the poetry of darkness and simple form—from the quietism of Chardin to the meditative interiors of Hammershøi and the spare spirituality of modern minimalists. Its language of reduction and interior light remains legible to viewers accustomed to visual noise.

Iconography and Meaning Without Excess

Despite its minimal props, the iconography remains unambiguous. The saint’s nearly naked body and rough cloth mark penitence; the cross-staff links prophecy to Christ; the lamb places salvation within reach; the desert names the space of preparation. De la Tour’s achievement is to deliver all of that without clutter. He trusts viewers to supply narrative from memory while he supplies the state of soul. That trust feels like a kind of respect and contributes to the painting’s durable authority.

Why the Painting Feels Contemporary

To contemporary eyes trained on photography and abstraction, this Baptist seems startlingly modern. Large dark fields, a near-monochrome palette, a figure designed by planes and edges, and an absence of anecdote—these traits align the painting with twentieth-century sensibilities. Yet the work never abandons human warmth. The arm’s orange glow, the lamb’s gentle oval, and the soft fall of hair keep the picture on the side of mercy rather than austerity for its own sake. De la Tour shows that simplification, handled with love, can enlarge rather than starve experience.

Conclusion

“St. John the Baptist in the Desert” is a masterpiece of concentrated meaning. In a handful of forms—diagonal body, vertical staff, small lamb, and an ocean of quiet dark—Georges de la Tour creates a complete theology of vocation. Light is grace; the desert is inward; strength is calm; witness is prepared in silence. The saint’s bent head and resting hands teach not resignation but readiness. Nothing is wasted; nothing is decorative; everything is poised. Standing before this painting, we learn how to listen again, how to watch light arrive without spectacle, and how to let a few truthful forms carry the whole freight of hope.