Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

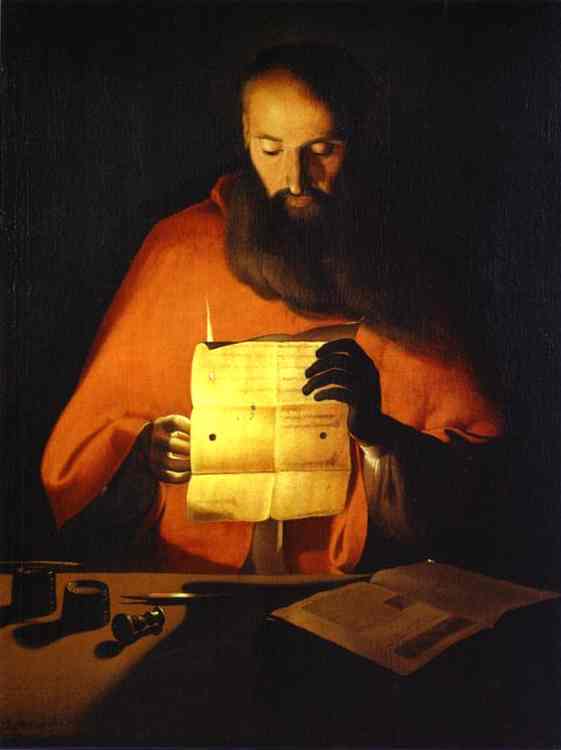

Georges de la Tour’s “St. Jerome Reading” from 1650 is one of the most eloquent nocturnes of the Baroque. In a room swallowed by darkness, an elderly scholar bends over a sheet of paper that blazes with internal light. The candle hidden behind the page turns the parchment into a small sun, carving St. Jerome’s head and hands into sculptural relief. A red mantle presides over the scene like a field of warm gravity, while on the table an open folio, a seal, a pen case, and other instruments of study rest in a tight constellation. With astonishing economy, de la Tour fuses devotion, scholarship, and mortality into a single, lucid image of attention.

A Saint Defined by Reading

St. Jerome, the fourth-century translator of the Bible into Latin, appears here not as a desert ascetic but as a scholar at his desk. De la Tour anchors the identity through action rather than ornament. There are no lions, trumpets of fame, or towering libraries. The saint’s sanctity is expressed by the act of reading itself, treated as a vocation that demands the entire body. The head dips, the shoulders lean, the fingers brace the fragile sheet. The scene argues that holiness is not only a matter of visions and miracles; it is also the ability to submit the mind, night after night, to words that outlast the reader.

Chiaroscuro as Theology

De la Tour’s candlelight is more than a technical tour de force. The sheet of paper becomes a theological device, transmitting light while partially concealing its source. This glowing veil suggests how scripture mediates illumination: the fire is present yet gentled by the page, just as divine truth reaches the human mind through language. The saint’s downcast eyes receive the light indirectly, modeling humility as the right posture for learning. Shadow, far from being a void, protects the mystery, keeping the focus on the narrow arena in which comprehension is worked out.

The Miracle of Translucent Paper

Few seventeenth-century paintings render paper as persuasively as this one. The folded sheet shows soft creases and tiny pinholes; its edges curl as heat rises from the hidden flame. Where the candle’s wick kisses the page, the parchment blooms into yellow-white, then cools through honey and straw toward its edges. De la Tour records the sheet’s slight opacity where the folds double the thickness, and he mutes the glow under the saint’s fingertips. The result is a textbook in observational seeing, but it is also poetry. The paper is literally enlightening the face that reads it.

The Authority of Red

The mantle’s red is not theatrical but settled and weighty. It defines the saint’s presence as dignified, ecclesial, and warm. The mantle’s planes are simple and monumental; they hold the composition together as a single mass upon which the more delicate notations of hands and paper sit. Red also binds scholarship to charity, reminding viewers that Jerome’s learning served the Church and that knowledge without love would be cold. Against the red, the parchment’s lemon flame feels purer, and flesh tones, especially along the brow and nose, acquire a humane warmth.

Hands That Think

De la Tour gives the hands a role equal to the head. The left hand steadies the lower edge of the paper with a scribe’s tenderness; the right hand, partly darkened, pinches the top corner with decisive intelligence. Tendons rise, knuckles are flattened by pressure, and the thumb pads spread slightly from the sheet’s slick resistance. These are not soft ritual gestures; they are the practiced movements of a lifetime at the desk. The hands “read” as much as the eyes, and the painting implies that understanding is a bodily discipline.

A Still Life of Study

The band of objects across the table—the open folio, cylindrical containers, a seal, perhaps a pen case—form a quiet still life of scholarship. Their arrangement is compact but not fussy. Each object has a job. The large book, pages splayed, signals the weight of tradition; the seal suggests authority or correspondence; the small tools promise labor. De la Tour paints them without gleam or display, in keeping with his ethical realism. These are modest instruments through which immense cultural work was done.

Composition Built on Axes of Light

The painting’s structure is startlingly clear. A vertical axis runs through the saint’s head, paper, and hidden candle. A strong horizontal is laid down by the tabletop. The glowing rectangle of the page functions as the pivotal form tying both axes together. Around this cruciform geometry the curves of the beard and mantle soften the space, preventing any mechanical severity. The clarity honors the saint’s task: the world comes to order under the light of careful reading.

The Silence of Night

De la Tour’s nocturnes are secular hymns to silence. Here, sound is swallowed by the room. The saint’s breath seems slowed to match the candle’s measured burn. This quiet is not empty; it is fertility. The dark grants the reader freedom from distraction so that meaning can ripen. In the seventeenth century, when cities were loud with soldiers and markets, such silence held ethical weight. It championed the contemplative life not as retreat but as the condition for truthful action.

Material Truth and Spiritual Credibility

The artist’s devotion to surface—paper’s buckling, wax’s dull shine, cloth’s weight—creates trust. Because the painting tells the truth about what we can touch, we are more ready to trust what we cannot: grace arriving through words, transformation occurring in solitude. De la Tour’s realism is never cynical; it is sacramental. Things matter because they bear meaning. The paper glows, the wax warms, the book opens, and through these faithful details the invisible becomes plausible.

The Head as a Vessel of Light

Jerome’s head is rendered as a quiet vessel. Highlights pick out the brow ridge and the bridge of the nose; the forehead disappears into shadow; the eyes are lowered beyond the viewer’s access. The beard, abundant and soft, acts as a dam, catching the light as it cascades down from the paper. The head receives illumination rather than producing it, an iconographic reversal that turns intellect into hospitality. Learning, the image suggests, is a gift first, labor second.

Vanitas Without Display

Traditional symbols of mortality appear only indirectly. There is no skull on the desk, yet the candle and the curling paper are themselves vanitas emblems: flame exhausts its fuel; heat deforms the page; wax will drip and harden; study outlives the student. De la Tour’s restraint prevents the scene from becoming moralistic. Mortality is present as ambient fact rather than as lesson. That subtlety opens space for hope—the light is still burning, the page still readable, the hand still firm.

Relationship to the Artist’s Other Jeromes

This painting converses with de la Tour’s other treatments of the saint. In earlier works Jerome kneels in a desert cell, clutching a cross and a rope scourge. In the 1620s he peers at a letter through a small lens. The 1650 version synthesizes both modes. The scholar and the penitent coexist: the desk replaces the cavern, but the face’s concentration carries the same penitential seriousness. Compared to the youthful experiments, the late Jerome is more distilled. Fewer objects, larger forms, and a single incandescent device carry the drama.

Historical Weather

Painted in a region scarred by the Thirty Years’ War, the work resonates with the need to rebuild intellectual and spiritual life. The humble tools of learning gather like survivors around the fire. The choice to picture Jerome reading a letter—rather than enthroned or triumphant—would have felt pastoral and practical to de la Tour’s contemporaries. It suggested that the way forward after devastation was not spectacle but fidelity to texts and to the quiet labor of understanding.

Technique and the Discipline of Edges

De la Tour’s paint handling is a masterclass in restraint. Edges facing the light are crisp, while those melting into shadow dissolve into soft transitions. The sheet’s perimeter is drawn with knife-like clarity, but the red mantle is built from broad, matte planes. Flesh is constructed in measured facets rather than sugary blends. This disciplined economy mirrors the saint’s own discipline. Just as Jerome pares away frivolity to concentrate on meaning, de la Tour removes painterly noise to let form and light speak.

The Candle You Cannot See

Hiding the candle behind the paper is both a compositional and symbolic masterstroke. The invisible source organizes everything we do see: the range of yellows, the strength of cast shadows, the way objects on the table bloom or recede. It also invites meditation on mediation itself. We do not look at the flame; we look at what the flame reveals. Likewise, we do not stare at mystery directly; we attend to the words, people, and practices through which it becomes intelligible.

Reading as Vocation

The painting honors reading as an act that shapes the reader. The lowered eyes, steady hands, and supported back announce that this is not casual scanning but covenantal attention. In an age that often prizes speed, de la Tour’s Jerome reintroduces slowness as a virtue. The saint holds the page close enough to feel its warmth; he reads within the breath radius of the flame. The entire scene is a pedagogy of nearness, insisting that the mind learns best when the heart and body are also present.

Viewer as Participant

De la Tour places the table flush with the picture plane, inviting viewers into the circle of light. We stand where another book might sit. The intimacy is disarming. Because the saint ignores us, we are free to adopt his posture rather than seek his approval. The composition thus transforms spectators into apprentices. Many images preach; this one tutors by example.

Legacy and Modern Resonance

“St. Jerome Reading” anticipates modern explorations of minimal means and maximal meaning. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century painters of interiors and night—Chardin, Hammershøi, Hopper—owe something to de la Tour’s courage in letting a single light source craft a world. The painting also speaks uncannily to contemporary life saturated with backlit screens. It offers a counter-image: a human face warmed by living flame, eyes escorted by darkness toward a text that does not scroll away.

Conclusion

Georges de la Tour distills the identity of St. Jerome into an act of reading that glows at the center of a disciplined composition. Paper, flame, hands, beard, and book conspire to show learning as devotion and light as a gift mediated by text. The painter’s commitment to material truth deepens the spiritual claim until the two are inseparable. In this calm chamber of night, scholarship becomes prayer, and silence becomes the workshop where understanding is forged. The image endures because it is not merely about a saint long gone; it is about the way attention itself can turn a small piece of the world into a sanctuary.