Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

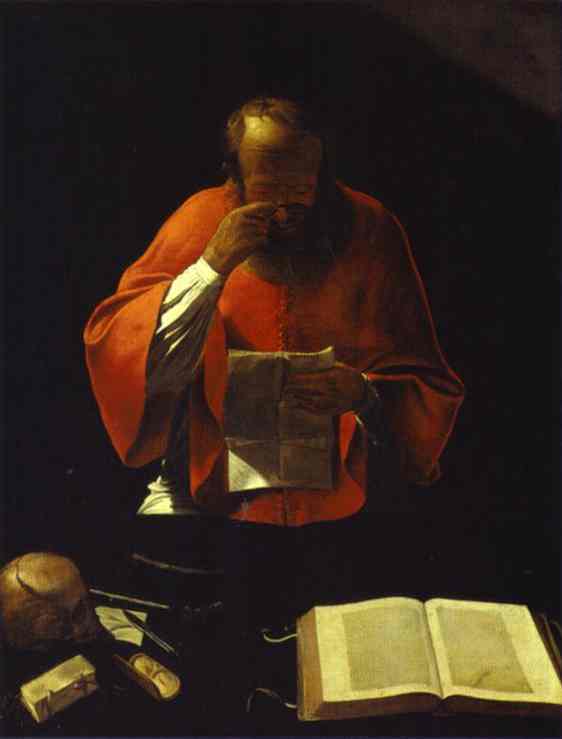

Georges de la Tour’s “St. Jerome Reading” (1638) distills scholarship, faith, and aging into a night scene of elemental clarity. The scholar-saint stands before a dark field, wrapped in a red mozzetta that reads as a single architectural plane. His head bows into the cone of light; one hand steadies a folded sheet, the other pinches a pair of eyeglasses whose lenses hover just before his eyes. On the table, an open book lies like a pale island, flanked by a skull, a seal, a quill, and scattered slips. Nothing else intrudes. By compressing the world to objects that the mind genuinely uses, de la Tour converts an emblem of learning into an intimate portrait of attention—how understanding happens, minute by minute, under a lamp that must be tended.

Composition and the Architecture of Reading

The composition is built upon two interlocking geometries. The first is the red triangle of Jerome’s figure, the mozzetta dropping from the shoulders in wide planes that converge toward the waist. This triangular mass anchors the upper half of the canvas and funnels the eye toward the small rectangle of paper he reads. The second geometry is the tabletop still life, arranged as a horizontal counterweight: at the far right, the open folio; at the far left, a skull beside writing tools; in the middle, a low darkness that keeps each object from crowding another. These two geometries—standing triangle, reclining bar—hold one another in equipoise. The arrangement is not theatrical; it is useful. The scholar stands to read a letter in hand, while the books and instruments lie ready for when his eyes leave the page. In this way the composition models the actual choreography of study.

Light as Moral Weather

De la Tour’s handling of light is famously exact, and here it forms the painting’s ethics. A single source—offstage, slightly to the right—strikes the open folio first, then climbs to the lower edge of the letter, then licks the bridge of Jerome’s nose, the rim of his glasses, and the tips of his fingers. The skull at left receives a quieter glow; writing tools catch thin glints; the rest of the room collapses into breathable dark. The order of illumination clarifies the hierarchy of attention: text, then reader, then the memento of mortality and the paraphernalia of labor. In this moral weather, nothing is flashy; brightness is rationed like a resource. The discipline of the light becomes the argument of the picture: truth is found where light is placed with care.

Chiaroscuro Without Spectacle

While the painting belongs to the Caravaggesque tradition of single-source night scenes, de la Tour prefers large, calm planes to broken, dramatic highlights. The red mantle reads as big fields of tone with a few tight ridges where the fabric creases. Jerome’s face emerges in slow gradients: brow and bald pate descend into shadow before the glasses and letter pull the eye back to a narrow blaze. On the table, the open book is a plane with two luminous pages divided by a central fold, its clarity granted by a handful of edges and one tempered highlight along the bottom edge. This quiet chiaroscuro respects the activity it depicts. Reading is an art of sustained attention, and the light performs the same steadiness.

The Eyeglasses and the Biography of Age

Few Baroque paintings have given spectacles a more dignified part. Jerome’s glasses are not props but tools in use. He holds them poised with two fingers, as if adjusting focus while following a sentence down the page. The gesture admits bodily limitation without embarrassment: aging eyes need help, and the mind, undeterred, acquires what the task requires. De la Tour’s inclusion of the glasses emphasizes the material truth of scholarship. Knowledge is not a supernatural infusion; it is a labor that uses lenses, oil, paper, and bone.

The Letter as Event

Unlike the permanent texts represented by the open folio, the folded sheet Jerome reads is transient. Its creases catch light; its top edge lifts slightly where the hand supports it. It carries news or argument or appeal from a specific person at a specific moment. In making the epistle the focus, de la Tour animates the scene with time. We are present for a particular paragraph being understood right now. The saint-scholar is not withdrawn into timeless meditation; he is inside a conversation, responsive to words that travel across distance. The letter bridges the scholar’s seclusion and the world’s needs—exactly the bridge Jerome’s Vulgate translation has served for centuries.

Books, Skull, and the Mechanics of Thought

De la Tour’s still life is both emblem and inventory. The open book—probably scripture—represents the stable canon against which all other texts are measured; its heavy pages buckle slightly, proof of use. The skull is the memento mori that paces study: knowledge without wisdom is vanity; time is short. Yet the skull is not a grotesque; it rests in shadow with the calm of an old companion. The seal, quill, and slips acknowledge the administrative texture of a scholar’s actual day—documents to sign, references to track, notes to ferry from book to letter. By dignifying these items with the same fair light given to the saint’s face, de la Tour declines the romance of erudition in favor of its practical truth.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The palette is a restrained chord: red of mozzetta; warm ochres and umbers of table and skull; parchment cream of pages and letter; deep blacks that hold the scene. Because chroma is limited, temperature performs emotional work. The warm red—neither scarlet nor purple—conveys intellectual heat disciplined by ecclesiastical duty. The parchment’s creamy glow reads as humane and inviting; the darks, though deep, are not cold. The harmony creates an atmosphere in which thinking feels possible and desirable. Nothing shrills; all hums.

Gesture and the Psychology of Concentration

Jerome’s pose is a masterpiece of economy. Shoulders slope; head bows; one hand clamps the paper and half-raises the glasses; the other steadies the sheet at its lower edge. The mouth is concealed by hand and beard, but the posture speaks: he is somewhere between reading and rereading, testing the sentence’s claim against what he knows. This tiny interval—the quarter-second before a line turns into assent or dissent—is what de la Tour suspends for us. Many paintings glorify the moment of revelation; this one honors the lesser, crucial moment of verification.

Space, Silence, and the Chamber of Night

The background is not a room so much as a volume of useable dark. Rarely has silence been more convincingly painted. We can feel the hush that protects the exchange between mind and text—the way a lamp isolates a circle of sight and lets thought breathe. There are no shelves, no windows, no architecture clamoring for attention. The void is a choice that keeps each object audible. When painters trust negative space, they confer dignity on attention itself, and de la Tour is the master of this trust.

The Theology of the Table

Despite its simplicity, the tabletop reads like an altar of tools. Objects are spaced with liturgical care: the open book like a missal; the letter like a host of meaning to be discerned; the skull as the relic reminding preacher and reader that every sermon is addressed to the dying; the seal and quill as the instruments by which truth passes to others. The arrangement avoids allegorical hysteria; it is practical and therefore persuasive. Theology in de la Tour is never divorced from craft.

Humanism Without Sentimentality

What distinguishes this image from many pious portraits is its human scale. Jerome is not a marble saint glowing with superhuman vigor; he is an old man with tired eyes, a good light, and work to do. The red garment is sumptuous but treated as a flat plane rather than a display of luxurious texture; it honors office more than status. The skull sits, the book waits, the letter demands. This temperate humanism keeps the image from aging into cliché. Viewers recognize the rhythm of their own focused hours, whatever their field.

Comparisons within de la Tour’s Jerome Cycle

De la Tour returned to Jerome repeatedly. In some versions the saint peers through a hand-held lens; in others, he reads a letter with eyeglasses, or he bends over a page while the lamp burns in a clear glass. This 1638 composition is among the most abstract, nearly modern in its reliance on big shapes and a dominant field of black. Compared with earlier “reading” Jeromes, the figure is more monumental, the table more spare, the light more judicial. The evolution suggests an artist moving from anecdote to essence, trusting fewer means to say more.

Technique, Edge, and Plane as Persuasion

The picture’s authority rests on de la Tour’s decisions about edges. He tightens the rim of the folio so the book “reads” instantly as a real object; he softens the skull’s contour where shadow drinks it, keeping the memento from stealing attention; he chisels the upper edge of the letter and then lets the lower half dissolve into the saint’s red mantle, binding text to reader. Brushwork hides inside these planes; glazes warm the reds; a few scumbles keep the paper from becoming sugary. The technique is so disciplined that it nearly disappears, which is the point. If the paint calls attention to itself, the reader’s attention would wobble. Instead, the painter’s restraint becomes an argument for the life of the mind.

Time, Mortality, and the Pace of the Page

The skull’s presence, the spectacles’ necessity, and the letter’s ephemeral paper together articulate a philosophy of time. Pages endure longer than bodies; letters age into archives; yet all reading happens under a lamp whose oil runs down. De la Tour threads this knowledge through the scene without rhetoric. The saint’s small act of adjusting his lenses becomes a compact manifesto: acknowledge limits, employ tools, keep reading. The speed of the painting is the speed of a page turn.

The Viewer’s Role and the Ethics of Looking

We are placed just beyond the table, at the level of the open folio, as if invited to read with the saint. No one meets our gaze; our duty is to respect the concentration before us by mirroring it. The painting teaches an ethic of looking: be steady, be fair with light, let objects be themselves, do not rush. In a culture of visual noise, the canvas feels like a vow of hospitality to attention.

Modern Resonance

Despite its seventeenth-century garments, the picture reads with startling currency. Replace the quill with a pencil and the oil lamp with a desk light, and the choreography remains: an older worker adjusting glasses to parse a paragraph, the table scattered with notes, the room dark beyond the project’s circle. The lesson is the same whether one studies scripture, code, contracts, or medical charts: gather your tools, set the light, read the sentence again. De la Tour’s image celebrates that durable discipline.

Conclusion

“St. Jerome Reading” is a nocturne of thought, a painting that trusts a few truthful things—paper, lens, lamp, book, bone—to carry the weight of a long vocation. Composition knits figure and still life into a grammar of attention; light assigns priority without theatrics; color keeps the mood sober and humane; texture persuades us that the objects are real enough to use; gesture suspends the precise instant when reading becomes understanding. In honoring scholarship as labor sustained by small instruments and fair light, de la Tour gives the modern viewer a model of seriousness that is both modest and immense. Nothing is wasted. Everything is necessary. The page waits; the mind answers.