Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

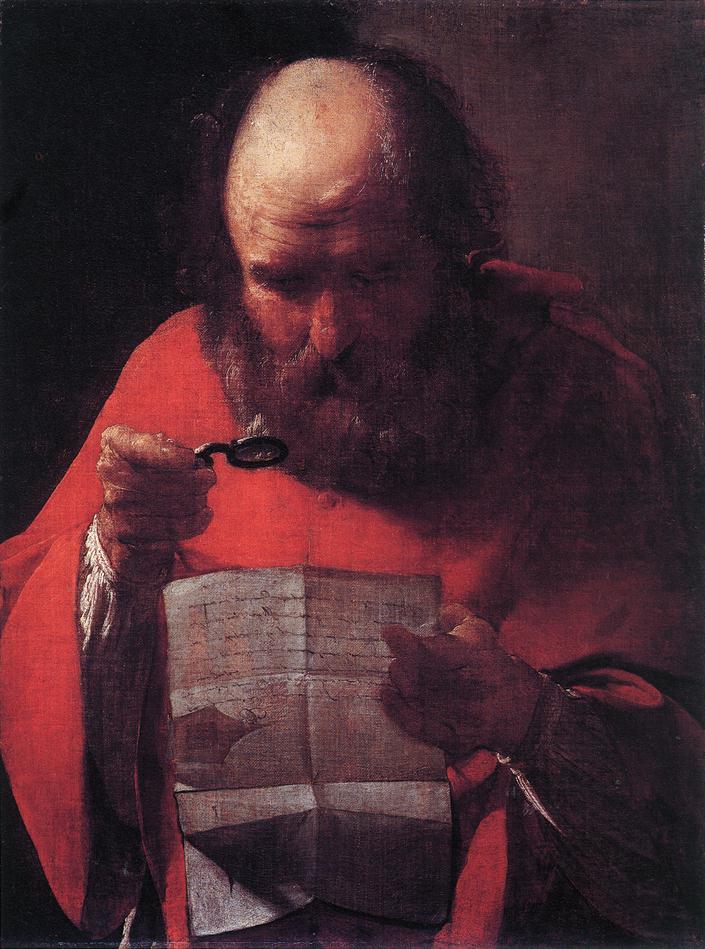

Georges de la Tour’s “St. Jerome Reading” (1623) transforms a familiar subject—the scholar-saint absorbed in text—into a compact meditation on attention itself. The canvas shows an elderly man with a bald crown and heavy beard, wrapped in a red mantle that glows like banked embers in a dim room. He leans over a folded document, holding it close while a small monocle or reading glass lifts toward the lines. The background is austere, a near-solid dusk that grants the figure an almost sculptural presence. Nothing distracts: no wilderness, no lion, no temple of learning. De la Tour reduces the icon to a single act—reading—and lets light, fabric, paper, and flesh stage a drama of intellect and devotion.

Composition and the Architecture of Looking

The painting’s structure is as economical as its subject. De la Tour builds a triangle whose apex is the bald head and whose base is the broad, pale rectangle of the paper. The right edge of the mantle forms one side of the triangle, falling in a long, measured slope; the left side is described by the saint’s bent arm raising the lens. Between these lines sits the hollow of shadow that protects the eyes, a small chamber where thought forms. The paper and the lens create a hinge: reading requires both object and instrument, page and focus. De la Tour makes that hinge visible. The page is tipped slightly, catching light with just enough cant to reveal its creases and illegible script; the lens rises on an answering diagonal, knitting eye to text without fully touching it. The entire composition is a machine for attention.

Light as Spiritual Grammar

Illumination enters from high left and descends in deliberate steps—bald crown, bridge of nose, knuckles, page—before dissolving into the room’s brown-red dusk. The light does not lecture; it clarifies. On the skull it spreads as a wide, matte glow, implying a mind made available. On the beard it breaks into smaller, granular notes, registering the roughness of age. On the page it grows cool and planar, insisting on legibility. Everything in between—the cavern of eye sockets, the red folds, the wrist’s shadow—is moderated to keep the viewer’s path of reading unbroken. In de la Tour the beam is never mere optics; it is a moral weather that selects what deserves visibility. Here it names the stages of understanding: openness at the brow, concentration at the eyes, touch at the hands, and comprehension on the page.

The Red Mantle and the Body’s Heat

The garment is not decorative background; it is a thermal field. Its red is not the explosive scarlet of spectacle but the deep, slow warmth of habit. Where light skims the shoulder, the mantle flares toward orange; where it turns into shade, it browns to a wine-dark quiet. This chromatic breathing gives the body heat, the visible aura of concentration. St. Jerome’s study has often been painted as a cold monastic cell; de la Tour, by contrast, makes thought corporeal. The mantle protects and anchors, holding the saint’s torso still so the mind can move.

The Paper as Engine of Time

De la Tour treats the paper with unusual respect. It is large enough to occupy the lower half of the image, and its creases are plotted like topography. The text is suggested, not spelled out: a rhythm of thin lines that stand in for words, a few darker strokes to imply signatures or marginalia. Most persuasive is the sheet’s history—folds, soft corners, a triangle turned up where a crease resists flattening. Reading here is not about a timeless book but about a document that has been pocketed, opened, and reopened. It’s a page from life. The saint’s thumb bruises the edge; the other hand steadies the sheet’s weight. The material truth of paper becomes a metaphor for memory: thought is an act of unfolding.

The Lens and the Ethics of Precision

The tiny lens between fingers and face is the painting’s quiet surprise. It confirms a body that ages and adapts. It also signals intellectual humility: truth requires help. De la Tour suspends the glass just before it meets the eye, capturing an instant of calibration—the distance where focus clicks. The detail converts the saint’s devotion into a method. He does not stare himself into comprehension; he equips his sight, checks it, and only then proceeds. This ethics of precision is as theologically charged as any skull or crucifix: it honors a Creator by refusing to read lazily.

The Face and the Psychology of Silence

Jerome’s head is lowered, his gaze tunnelled by brow and lens, his mouth hidden in beard. The downward tilt closes the figure’s expression to the viewer, redirecting our curiosity toward the act rather than the actor. Yet the psychology is palpable. Furrows in the bald dome register years of habitual concentration; the bridge of the nose carries a ridge of light like a drawn rule; the cheeks sink into shadow where breath slows. De la Tour declines theatrical pathos. He shows thinking as a physical labor marked not by heroic strain but by steadiness. In this privacy the painting finds dignity.

Texture and Surface

The painter’s touch is restrained but exact. The bald scalp is built from thin layers that let warm underpaint breathe through, mimicking the translucence of skin. The beard is massed broadly, then teased with a few lifted bristles along the lip and chin. The mantle’s weight is established in large planes before seams and hems are tightened with small accents. The page is rendered with a mixture of cool grays and low whites that read as both light-catching and fibrous. The lens, delicately dark, bears a minute highlight at its rim, just enough to convince the eye. The surface never shows off; it maintains the same discipline it depicts.

Space, Corner, and the Chamber of Study

The setting is a corner: darkness at left, a warmer plane at right. This corner motif, which de la Tour used repeatedly in his early apostolic series, functions as a structural metaphor. Thought requires edges to press against. The saint sits in the angle where privacy becomes presence. The background’s near-void is not an absence of world but the necessary subtraction of distractions, a carved space where reading can gather force. In this chamber the smallest events—a crease turning, a knuckle catching light—have room to signify.

Iconography Trimmed to Essentials

Traditional images of Jerome parade attributes: a skull for mortality, a lion for legend, a cardinal’s hat for office, a crucifix for penitence. De la Tour trims the inventory. What remains is the most basic pairing: text and reader. The red garment hints at ecclesial dignity without insisting on it. The folded paper, rather than a monumental codex, hints at correspondence—letters rather than treatises, the living exchange of ideas across distances. The effect is to humanize the saint without diminishing him. He becomes a model for any labor that depends on sustained attention.

Rhythm of Hands and the Body’s Compass

The left hand lifts the lens; the right hand steadies the document. Between them the page tilts. The triangle formed by these three points is the body’s compass for reading. De la Tour calibrates each angle with care, so that the gesture feels inevitable. The painter has a sculptor’s sense of how a pose carries meaning: a few degrees more or less and the scene would collapse into fatigue or strain. As painted, it reads as endurance—work that is difficult but suited to the worker.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The canvas rests on a dialogue between warm reds and cool grays. Flesh mediates: on the head it blooms toward peach; on the hands it cools to clay in shadow. The page is the coldest element, a crisp plane that disciplines the reds around it. This temperature map produces composure. Warmth locates the human source of energy; coolness gives that energy a rule to follow. In lesser hands, red might have romanticized the scholar into a beacon; de la Tour’s balance keeps passion and clarity in accord.

Dialogue with De la Tour’s Earlier Saint Jerome

Three years earlier, de la Tour painted a penitential “St. Jerome” kneeling nearly nude with cross, cord, and skull. The 1623 “Reading” offers a different facet of the same life. The earlier work honors contrition; this one honors comprehension. What unites them is a conviction that essentials suffice. A small light and a few objects tell the truth about a person when placed with exactness. The later candlelit masterpieces will make this method even more austere. Here the light is broader, but the ethic is the same: stage as little as necessary so attention can be as large as possible.

Sound, Time, and the Slow Pulse of Reading

Though silent, the painting has tempo. You can feel the beat: inhale, line of text, pause; shift the lens, re-enter the sentence. The creases on the page act like bar lines; the red cloak holds the long notes. Time expands around the act, not because anything momentous happens, but because ordinary concentration is allowed to fill the frame. De la Tour’s gift is to grant the modest rhythms of study the dignity usually reserved for miracle or martyrdom.

Realism Without Cruelty

Aging skin, worn beard, and imperfect nails are recorded without apology. Yet there is no cruelty in the realism. The man’s body is treated as capable, not decrepit. Even the lens is not a symbol of decline but an instrument of extension. The painting suggests a theology of embodiment in which tools are not cheats but gifts that allow the mind to serve longer and better. It is an image of grace as accommodation rather than spectacle.

The Viewer’s Role

The viewer stands at desk distance, close enough to read the exposed planes of paper and skin, close enough to feel the red’s warmth. But we are not allowed to read over the saint’s shoulder; the text remains general. Our role is not to seize content but to adopt posture. The picture teaches by example: slow your eyes, calibrate your tools, accept the necessary quiet, and let a modest light do its sufficient work. In this way, the painting becomes not only a representation of attention but also an instrument for producing it in the beholder.

Technique, Edge, and the Measure of Restraint

Much of the image’s persuasion comes from de la Tour’s flawless management of edges. Where the page meets the shadowed mantle, the boundary is crisp; where beard dissolves under nose, it softens; where the skull turns from light, the edge is neither sharp nor blurred but timed, a transition proportionate to curvature. These micro-decisions accumulate into trust. We believe the world of the painting because its edges behave like edges in lived experience. Such restraint looks simple until one attempts it; then it proves the highest craft.

Modern Resonance

“St. Jerome Reading” speaks uncannily to a contemporary world saturated with information and impoverished in attention. De la Tour’s saint is a patron of deep work. He refuses ornament, closes the door on distraction, and lets a modest tool extend his capacities. The red garment can be read as the warmth of focus in a cold environment; the page as the stubborn materiality of knowledge in an age of flicker. Without preaching, the canvas proposes a humane technology of concentration.

Conclusion

With a head bowed to a page, a lens poised between, and a mantle that gathers the body’s heat, Georges de la Tour turns the ordinary act of reading into a quiet monument. The painting honors a life in which understanding is a form of devotion and precision an act of love. Its power lies not in spectacle but in sufficiency: a single figure, a plain room, a steady light, and the material facts of paper and glass. In this modest stage, thought becomes visible and time grows patient. “St. Jerome Reading” remains an enduring lesson in how to see and how to know.