Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

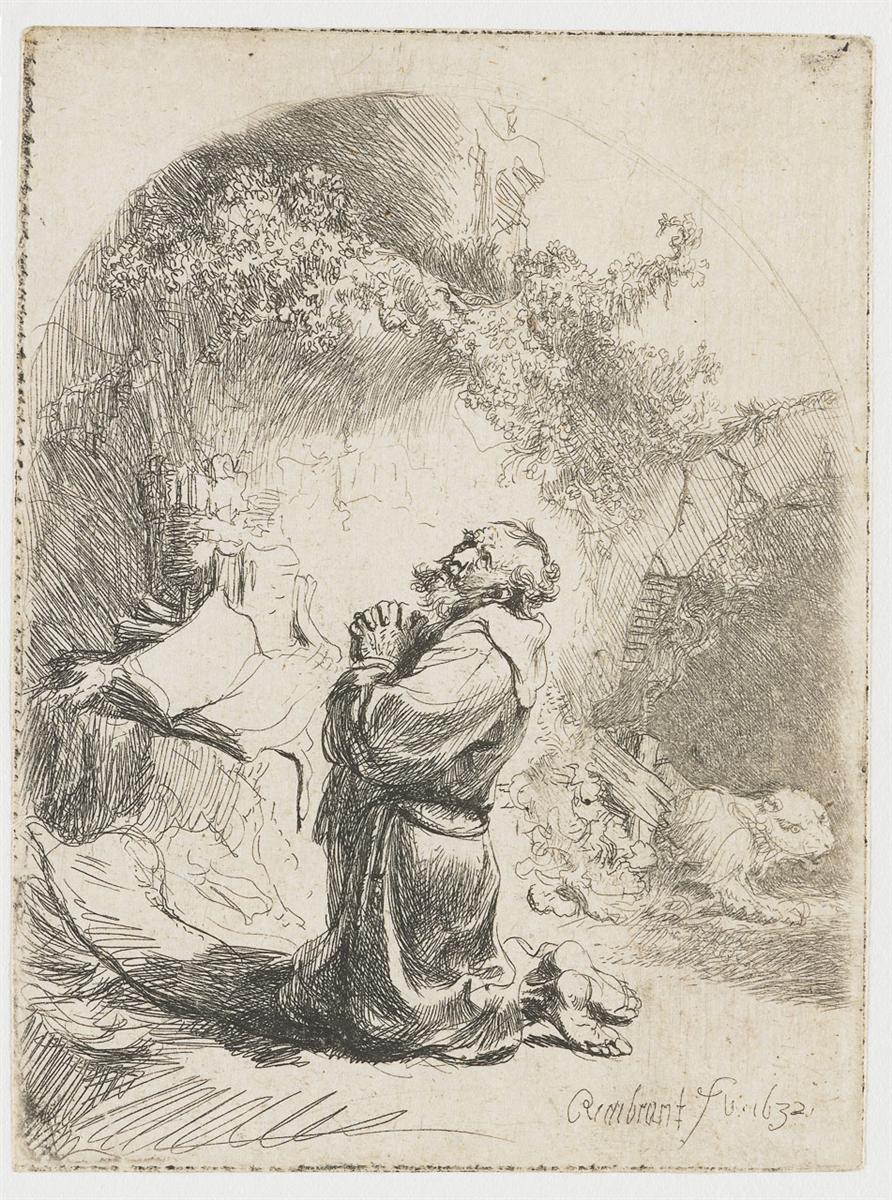

Rembrandt’s “St. Jerome Praying” from 1632 presents a kneeling saint in a rocky grotto, hands clasped and head lifted toward a clearing of light. The work is not a painted canvas but an etching, a medium the artist explored with remarkable freedom at precisely the moment he was establishing himself in Amsterdam. The spare palette of black ink on pale paper obliges Rembrandt to conjure atmosphere, texture, and spiritual intensity through line alone. What results is a quiet drama of devotion, built from whorls of hatching, sudden reservoirs of paper white, and a feeling of breath held in prayer. The print compresses narrative into posture and place: a hermit scholar interrupts study to address the invisible, while the lion—Jerome’s traditional companion—lies at ease nearby. The image is intimate enough to fit in the hand yet expansive enough to suggest the immensity of the divine.

Historical Context

The year 1632 marks Rembrandt’s early Amsterdam period, when the young master leveraged Leiden training, Caravaggesque light, and a taste for close observation into a new urban style. He was simultaneously developing a reputation as a portraitist and an experimenter in printmaking. Etching offered a market-friendly medium that could be sold to collectors in multiple impressions, while also giving the artist space to improvise. The Saint Jerome subject connected him to a longstanding European tradition. Jerome, translator of the Latin Vulgate, embodied the union of scholarship and asceticism cherished in Northern devotional culture. In the Dutch Republic—largely Protestant yet hospitable to images as vehicles for contemplation—Jerome appeared less as a specifically Catholic icon and more as a moral exemplar of study, penitence, and solitary integrity. Rembrandt’s print participates in this wider Dutch appetite for images that prompt introspection without ostentation.

Etching Technique and the Language of Line

Etching differs from engraving in that the design is drawn with a needle through a wax ground on a metal plate before acid bites the exposed lines. The method favors spontaneity and varied pressure, a perfect match for Rembrandt’s instinct to think through drawing. In “St. Jerome Praying,” the line quality shifts from hair-fine filaments in the distant foliage to robust, almost calligraphic strokes in the habit’s folds. Cross-hatching builds a hushed penumbra that curves around the saint like a half-dome, while strategic reserves of unbitten paper create the effect of light falling from an unseen opening above. The handling is both economical and abundant: economical in the sense that many forms are indicated with a few decisive gestures, abundant because the density of marks blooms into textures—moss, stone, cloth, beard, fur—that feel palpably present.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition places Jerome in profile, kneeling on a soft slope within a cavern that opens toward a leafy exterior. The curve of the cave’s mouth frames him in a large arc, a visual nimbus formed not by color but by gradations of hatch and paper. The saint’s upward glance aligns with the arcing boundary of darkness, directing the viewer’s attention to the luminous void rather than to a depicted deity. The right foreground contains the prone lion, rendered with a few relaxed curls of line, and a stair-like structure that recedes toward shadow. To the left, draped fabric and scattered volumes signal interrupted study. The whole scene reads as a sequence of nested spaces: the intimate ground where the saint kneels; the encompassing grotto; the hinted landscape beyond; and, above, the immaterial space of prayer. The arrangement keeps the figure central without isolating him, allowing setting and gesture to collaborate in a single mood.

Light, Shadow, and the Idea of Illumination

Without pigment, Rembrandt forges light through contrast. The upper left quadrant brightens into the near-whiteness of the paper, which doubles as both literal illumination and metaphor for grace. The darker hatchings pool behind Jerome, creating a backlit effect that edges his profile with brightness. This inversion—light derived from absence, shadow from accumulation—mirrors the logic of prayer in the wilderness: spiritual presence reveals itself where the world thins out. The handling of light also disciplines the eye. We first read the kneeling figure, then register the lion and study objects, and finally drift outward to the distant foliage where tiny marks suggest leaves vibrating in sun. No single area screams for attention; instead, the light graduates gently, making stillness the dominant sensation.

Iconography and the Meaning of Jerome

Jerome’s iconography typically includes a lion, a skull, a crucifix, and a book or stone. Rembrandt chooses a lean set of attributes. The lion rests contentedly, its tail and mane barely suggested, reminding us of the legend in which Jerome removed a thorn from the animal’s paw, earning its devoted companionship. Books lie rumpled at the left, their presence acknowledging Jerome’s scholarly vocation without overwhelming the devotional theme. There is no skull or crucifix in explicit view, yet the saint’s lifted gaze implies a focus beyond the frame. This restraint aligns with the Dutch taste for understatement and for images that invite the viewer to complete meaning in contemplation. The absence of theatrical symbols makes the work feel immediate and human. Jerome is not a remote allegory but an aging man, creased and barefoot, whose body enacts belief through posture.

Gesture, Anatomy, and the Performance of Prayer

The prayer’s intensity resides in the configuration of limbs, head, and hands. The knees sink into the earth; the toes flex against ground; the fingers interlace; the chin lifts. Rembrandt draws these elements with a sensitivity that suggests firsthand observation of people kneeling, rather than reliance on studio conventions. The habit gathers around the body in waves, reinforcing the upward thrust of the torso and the inward concentration of the clasped hands. The head’s tilt is critical. It prevents the figure from feeling static; it implies speechless address, a listening as much as a speaking. The anatomy is not heroized. Jerome’s feet are large and humble, his back bent with age, his beard wiry. The humanness of this body is what persuades us that the surrounding light has meaning.

The Wilderness as Studio

Rembrandt’s etching constructs a wilderness out of line, secretive and airy. Fern-like scribbles create hanging foliage; deeper hatchwork suggests shadowed rock. The setting does not catalogue species or geology; it registers the feeling of a natural shelter where a person can pray unseen. This cave is also a studio. Its curving walls mimic the concave space of a painter’s or printmaker’s work area, a place where attention gathers and outside noise is absorbed. In that sense the work is a self-reflection on artistic practice. The saint withdraws to translate scripture; the artist withdraws to translate vision into marks. Both labors require patience, solitude, and faith that something invisible will become legible.

Comparison with Earlier and Later Jerome Images

Northern European art is rich with images of Jerome ranging from Dürer’s meditative engravings to the theatrical penitent Jeromes of Italian painting. Rembrandt’s version leans toward introspection rather than theatrical self-flagellation. It also differs from his own painted depictions where the saint sometimes appears as a scholar at a desk, surrounded by tomes and skulls. Here the scholar is stripped to essentials. The economy of the etching anticipates Rembrandt’s later prints, where he will achieve profound states with even fewer lines and more daring use of open paper. The 1632 date places “St. Jerome Praying” at the cusp between the smoother, descriptive manner of his early years and the increasingly expressive, broken-line language of the 1640s and 1650s. Even now one senses the artist’s willingness to let incompletion speak, to allow viewers to supply what is not spelled out.

The Lion and the Question of Companionship

The lion is at once symbol and character. Its presence reassures, converting the wilderness from a threatening space into a shared retreat. Rembrandt shows the animal in a pose of rest, head down, back legs tucked under, tail curled. The softness of the strokes used for its fur contrasts with the harder, craggy lines of the rocks, producing a tactile separation of living and inert matter. The lion’s relaxed posture mirrors the saint’s interior peace, suggesting that harmony extends from the human to the animal realm when prayer orders the soul. The animal’s docility also underscores an ethical dimension familiar to Dutch audiences: true authority pacifies rather than dominates.

Books, Drapery, and the Interrupted Task

At the left, a draped cloth spreads under a cluster of books. The arrangement implies that Jerome has been studying before turning to kneel. The cloth’s folds are a playground for Rembrandt’s pen, a soft cascade of strokes that feels almost audible. The books, with their discrete rectangles and bindings, provide a counterpoint of order to the wildness of the surroundings. They also anchor the saint’s identity as translator and scholar. Rembrandt does not depict elaborate bindings or calligraphic pages; he offers blocky forms with just enough detail to spark recognition, trusting the viewer’s knowledge of Jerome to complete the narrative. The suggestion is that study and prayer are not separate activities but phases of one vocation, each feeding the other.

Paper As Light and Silence

One of the marvels of Rembrandt’s printmaking is his willingness to let paper remain untouched. In this image the white at the top and around the saint functions as both physical support and pictorial substance. The uninked zones become bright mist, the breath of the cave, the nearness of the divine. They are also silence, the unsounded interval in music that makes sound meaningful. By resisting the urge to fill every space with marks, Rembrandt allows light to feel like a gift rather than a manufacture. The viewer senses something ungraspable occupying the empty region toward which Jerome looks, a blank that refuses illustration because what it signifies cannot be pictured.

Devotional Use and the Viewer’s Role

Small prints like this could be collected in albums, framed in domestic interiors, or handled privately during prayer. The scale invites personal encounter. The viewer is close enough to count hatchings and feel the pressure of the needle, a tactility that draws one into the saint’s world. The composition encourages emulation. The curving architecture enfolds not only Jerome but also the beholder, who may experience the same sheltered turn toward light. In this way the print functions less as a narrative scene than as a device for contemplation. It models a bodily geometry of devotion: knees to ground, hands to chest, eyes to brightness. Through repetition the print could foster a habit of attention in viewers, marrying aesthetic pleasure to ethical practice.

Theological Atmosphere without Polemic

The Dutch Republic’s confessional landscape was complex, with Reformed orthodoxy dominant but toleration extended to many groups. Rembrandt’s religious images often avoid polemical markers, and this print is no exception. There is no insistence on particular doctrine beyond the value of prayer, humility, and study. Jerome’s status as translator of scripture would have appealed across confessions, while his desert solitude paralleled the Protestant suspicion of ostentatious ritual. The work’s theologically neutral atmosphere probably contributed to its appeal among mixed audiences of collectors, scholars, and merchants, who prized images that ennoble private piety and learning.

Print Market, Editions, and Collecting

Etchings offered Rembrandt a flexible way to reach patrons beyond the studio. Plates could be printed in small batches, adjusted between states, or reworked years later. While the precise print history of this particular plate is a matter for catalogues raisonnés, the 1632 signature situates it in a year of vigorous experimentation. The presence of Rembrandt’s name and date at lower right does more than authenticate; it participates compositionally, balancing the mass of the kneeling body and the resting lion with a light, declarative flourish. Early collectors prized such signatures as signs of authorial presence, a guarantee that the touch they admired in the image also inscribed the margin.

Materiality, Wear, and the Life of the Plate

An etched plate changes as it is wiped, re-inked, and bitten again. Burrs are smoothed, lines deepen or soften, and the character of the impression shifts. Rembrandt understood this and often exploited it, sometimes leaving a film of plate tone to enrich shadow. In “St. Jerome Praying,” the sensitive variation in hatch density suggests that even small differences in inking could alter the mood—from crisp morning clarity to veiled twilight. This variability means that the print is less a single object than a family of closely related objects, each impression a moment in the plate’s lifetime. The theme of prayer thus finds a technical echo in the print’s own quiet transformations over time.

Relation to Rembrandt’s Self-Fashioning

Rembrandt’s fascination with scholars, hermits, and artists at work often doubles as a reflection on his own identity. The kneeling Jerome, who alternates between reading and praying, resembles the painter who alternates between looking and making. Both practices require discipline and openness to something beyond personal will. In presenting Jerome not in grand ecclesiastical vestments but in a simple habit with bare feet, Rembrandt aligns spiritual authority with humility, a value that also underwrites his preference for ordinary models and unidealized features in portraits. The print can thus be read as an ethical self-portrait of sorts, a statement about what kind of artist Rembrandt aspired to be—attentive, patient, receptive.

Emotional Tone and the Experience of Time

The print’s prevailing feeling is one of still, expectant time. Nothing moves rapidly. The lion dozes; the leaves drift; the saint listens. The etched marks themselves gather slowly, like hours nested into days of work. This slowness becomes a theological statement. Prayer does not force a result; it waits. Etching, too, is a medium of waiting—the waiting for the acid to bite, for the plate to be inked, for the paper to receive. The print teaches time as much as it depicts prayer, inviting the viewer to linger until the pale space above the saint begins to feel less empty and more present.

Conclusion

“St. Jerome Praying” distills a large theme into a small rectangle: how knowledge and devotion companion one another in the solitude of a life. Rembrandt achieves this not through elaborate symbols or crowded narrative, but through a choreography of line, light, and posture. The kneeling figure grounds the composition and secures its meaning, while the lion, books, and cave set a rhythm of earthly companionship, intellectual labor, and natural shelter. The print honors the capacity of humble tools to communicate exalted states. It shows how a needle on a copper plate, guided by a hand that knows both anatomy and feeling, can make visible the invisible itinerary of the soul. Across centuries, the etching continues to work as it was designed to do: to draw the eye inward, to clear a space for attention, and to suggest that the simplest acts—kneeling, looking up, holding still—can open onto immeasurable light.