Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

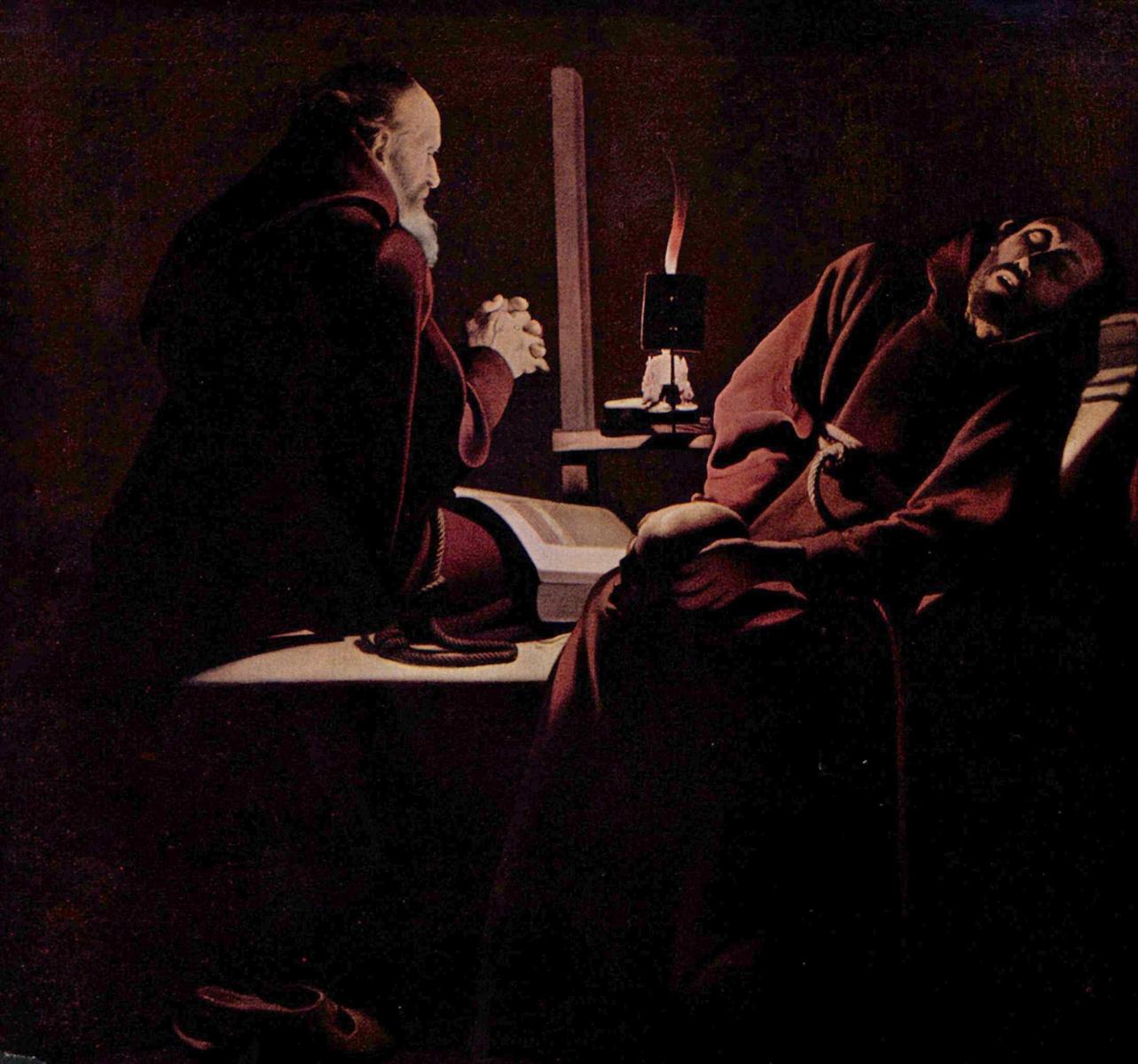

Georges de la Tour’s “St. Francis in Extasy, also called The Praying Monk beside the Dying Monk” (1640) compresses the drama of death, prayer, and companionship into a chamber where one candle regulates all meaning. Two friars in coarse brown habits occupy the scene. At left, a bearded monk kneels at a stone bench, hands locked, eyes lifted beyond sight. At right, another monk reclines, his head thrown back, mouth slack, body letting go. Between them a small candle burns behind a square screen, its flame a thin tongue that turns pages, faces, and cloth into a liturgy of planes. De la Tour refuses spectacle. He offers a truth that cloisters already knew: the most decisive hours arrive quietly, under a single light, while one person keeps watch for another.

Composition and the Architecture of Vigil

De la Tour organizes the canvas like a vigil tableau. The kneeling monk’s profile builds a compact triangle—back, shoulder, clasped hands—that leans toward the center. The dying monk creates a longer diagonal that reclines toward the same axis. The open book on the bench serves as a bridge: a flat, pale rectangle whose arc of pages points from the praying figure toward the extinguishing one. Behind, a stout candlestick sits on a narrow shelf, the flame shielded by a dark square pane that throws a vertical accent into the warm dusk. The composition thus forms a cross-like geometry: horizontal bodies, vertical light. The eye travels in a loop—praying hands to book to candle to face of the dying monk and back—so that the viewer participates in the act of keeping watch.

Light as Governing Ethic

De la Tour’s single flame controls not only visibility but hierarchy. First it names the book, then the praying hands, then the beard’s fringe and the rim of the cowl, and finally it breaches the darkness to model the dying man’s face and knuckles. The rationed distribution of brightness establishes the order of importance: the words of faith, the act of prayer, the person departing. Shadow is not menace here; it is a veil that protects the mystery unfolding in the small theater of light. The square screen before the candle is crucial. It keeps the flame from flaring, focusing the beam and casting an almost architectural silhouette that dignifies the scene with a quiet solemnity. Light becomes an ethic of fairness—each object receives what it needs and no more.

Chiaroscuro Without Theatrics

The painting belongs to the Baroque family of night scenes, yet de la Tour’s chiaroscuro remains serene. He molds forms with large, even planes rather than cascades of broken highlights. The praying monk’s habit reads as wide fields of seal-brown that crest along the shoulder and sleeve; the dying monk’s robe sinks into a slow sea of maroon shadows, from which the face rises like a pale island. The candle’s core catches here and there on the edges of pages, the ridge of a wrist, the corner of the flame-guard, but never shouts. This calm modeling synchronizes with the spiritual tenor of the subject: vigil is endurance, not spectacle.

Gesture and the Psychology of Presence

Every gesture rings true. The kneeling figure’s hands interlace with long practice; forearms rest on the bench so prayer can last. His head tilts toward light, not as rapture but as consent. Across from him, the dying monk’s mouth slackens, the hinge of jaw relaxed, neck exposed in a vulnerability that the heavy habit cannot disguise. One knee lifts gently as if following breath. The two bodies write the grammar of presence: an active keeping and a passive surrender, both dignified. No one clutches, no one dramatizes. The picture offers the psychology of a good death in community.

St. Francis and the Habit of Poverty

Although the title points to St. Francis, de la Tour resists individualized portraiture. The cowl, rope belt, and bare feet announce Franciscan poverty, but personalities dissolve into roles—watcher and watched—so that the scene reads as emblem and as record. Franciscan spirituality emphasized identification with Christ’s Passion, reverence for the poor, and joy within austerity. The painting converts these ideals into palpable choices: a cold stone bench instead of a bed, a single candle instead of many, a book bound in thick leather rather than gilt. The order’s charism is enacted in wood, wax, cloth, and silence.

The Book as Bridge Between Worlds

The open book glows like a low altar. Its pages cockle slightly along the gutter; a woven cord lies ready to mark the place. De la Tour never shows the text, and he doesn’t need to. The book’s presence declares that words are the proper companion of the dying and the sustenance of the living who remain. It literally supports the praying monk’s posture, turning reading into a physical prop for love. By placing the volume midway between faces, the painter makes it a bridge: from petition to consolation, from memory to hope.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The palette is a narrow chord of wine-dark browns, iron reds, and parchment ivory, tuned by the flame’s orange. This restraint allows temperature to carry feeling. The habits absorb warmth, deepening into maroon near the folds; the faces and hands borrow light in honeyed tones that never become sweet. The stone bench drinks the glow and gives it back coolly, reminding us of hardness beneath. Nothing jars. The chromatic discipline keeps the room hospitable to long attention—the visual equivalent of keeping a lamp trimmed through the night.

Texture and the Truth of Materials

De la Tour’s textures persuade by understatement. The friars’ wool reads as coarse, matte, and heavy; highlights lie on it like chalk rather than silk. The book’s paper has a shallow ripple that catches the edge-light; the leather cover is a dense, low sheen. The candlestick’s foot claims a single crisp glint, enough to prove metal. Even the stone bench carries a faint, powdery reflection that tells of grit under the forearms. Because each surface is trustworthy, the invisible realities—the prayer, the departure—become easier to believe.

Space, Silence, and the Cloister of Night

There is no window, no ornament, not even a crucifix in sight—only a wall that absorbs the candle’s little drama. This restraint converts space into silence. We can hear the small sounds the scene implies: the lick of fat melting on a wick, the papery intake of air through a tired throat, the whisper of a page turned earlier in the evening. Such silence is not emptiness; it is a medium. Vigil requires a room where nothing competes with what is happening to the heart.

The Candle as Clock, the Flame as Breath

The short candle, half-melted and haloed by its screen, turns time visible. Its perimeter of congealed wax indicates a burn already endured; its slender flame stands neither at the first spark nor the last gutter. We are in the middle watch: long past compline, not yet dawn. The flame’s narrow sway rhymes with the dying monk’s slack mouth and the praying monk’s stillness; together they trace the three conditions in the room—breath weakening, breath disciplined, breath consuming its own fuel. De la Tour writes a theology of mortality with physics.

Ecstasy, Death, and the Tender Paradox

The title’s word “Extasy” names the paradox at the picture’s core. Ecstasy means “standing outside oneself,” and the painting records two versions: the dying monk leaving the self by necessity; the praying monk leaving the self by attention. One body loosens, the other concentrates; both are departures from normal habit. De la Tour refuses to decide which is the greater miracle. Instead he knots them together so closely—hands to pages, faces to flame—that the viewer feels how love makes one person’s hour the other’s vocation.

Relation to De la Tour’s Other Nocturnes

This canvas converses with de la Tour’s single-light masterpieces. In the Magdalene series, flame and skull calibrate introspection; in “St. Jerome Reading,” the lamp governs scholarship; in “Education of the Virgin,” a candle disciplines learning shared between child and mother. “St. Francis in Extasy” extends the theme into the theology of accompanying the dying. The same ingredients—one light, large planes, sparse props—are deployed, yet the mood is darker, more saturated, as if the painter thickened the palette to match the gravity of last things.

Technique, Edge, and Plane as Persuasion

The painting’s authority rests on edges placed with musical economy. The squared silhouette of the candle’s heat shield is a single emphatic shape that grants the flame civic dignity. The praying monk’s clasped fingers are described by a few tight contours and one long highlight across the knuckles—enough to prove bone beneath. The dying monk’s profile is modeled by two decisions: a lucid ridge of light along cheek and brow, and a velvet shadow swallowing the eye. Brushwork hides inside these planes; glazes warm the cloth; scumbles give the wall a faint, living grain. The technique serves the truth that the scene is meant to protect.

The Ethics of Looking

De la Tour situates us just beyond the bench, inside the circle of light but out of the monks’ awareness. We are not invited to intervene; we are asked to keep watch with the living for the sake of the dying. The painting trains our gaze: do not pry at the last breath, do not dramatize prayer, do not turn suffering into theater. Hold the light. Read the page. Stay.

Humanism Without Sentimentality

What keeps the picture from pious cliché is its human scale. The friars’ feet are bare; their habits are heavy; their room is spare. The candle gives just enough. Yet the economy never curdles into bleakness. There is tenderness in the way the praying monk’s body leans toward his brother, in the way the book is placed where both can “use” it, in the decision to set the candle between rather than behind. De la Tour’s humanism refuses consolations that bypass truth, and because of that refusal, the final consolation—presence—feels earned.

Modern Resonance

Strip the habits from the figures and the scene remains painfully recognizable: a night in a hospital or hospice, one person drowsing in a chair, another slipping away, a dim lamp, a book open to steady the watcher’s mind. The painting’s discipline—large shapes, one light, few things—mirrors how crisis trims a life to essentials. It also offers a quiet manifesto for care: pay attention, keep the flame safe, let a text hold your hands when speech fails, give the dying your body’s proximity and your mind’s steadiness.

Conclusion

“St. Francis in Extasy (The Praying Monk beside the Dying Monk)” is a masterpiece of pared-down compassion. Composition arranges a corridor for fidelity; light sets a moral order; color keeps the temperature solemn and humane; texture roots meaning in believable matter; gesture makes theology visible in the simple exchange of keeping and letting go. Nothing is extraneous. Everything participates in the same work: to show how a good death is made when one person reads, prays, and tends the light while another person surrenders to the long night. De la Tour’s candle continues to burn, steady as a vow.