Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction: A Desert Father in Air and Light

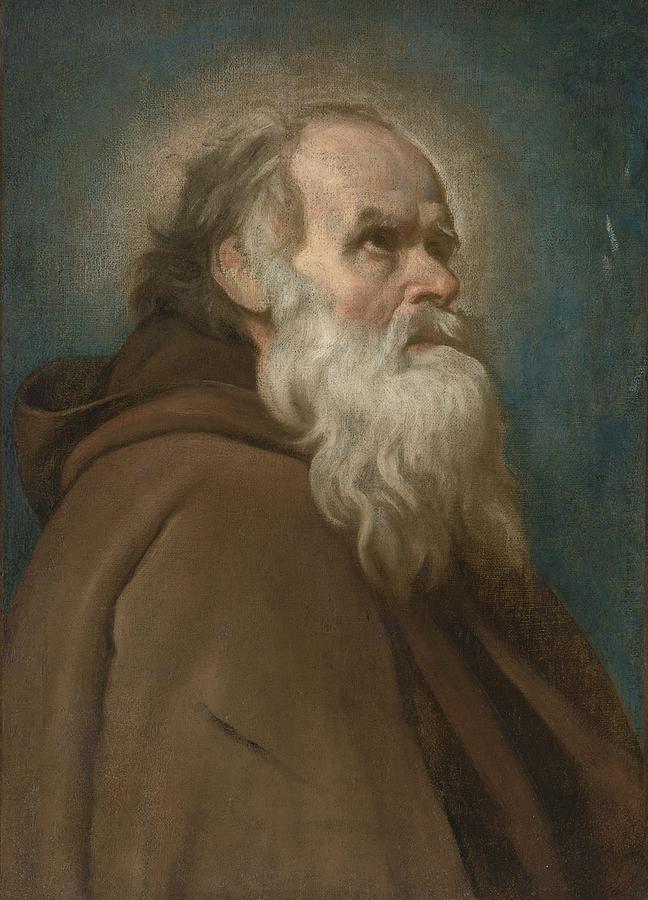

Diego Velázquez’s “St. Anthony Abbot” is a study in distilled sanctity. A bearded hermit turns his head toward an unseen radiance, shoulders wrapped in a coarse brown habit that breaks into soft planes of shadow. The background is a breathing blue-gray, and around the saint’s head glows a quiet aura—no metal halo, only the natural bloom that occurs when white paint feathers into surrounding color. The image is remarkably spare: no bell, no staff with its tau cross, no pig traditionally associated with the saint. Yet the painting convinces with a force that surplus ornament could never equal. It is holiness spoken in the language of air and light.

Historical Moment and Purpose

Velázquez executed this work in the late 1630s, a period when he was trusted not only to craft imperial images but also to supply devotional pictures for palaces and chapels closely tied to the Habsburg court. In Spain, the figure of St. Anthony Abbot—anchorite, healer, father of monks—embodied the ideal of withdrawal from the world in order to redeem it through prayer. The painter had recently delivered heroic equestrian portraits and grand battle epics; here he changes scale and ambition, building a picture that feels almost private. The turn to a solitary saint matches the Baroque conviction that God meets the soul most intensely in concentrated vision. Velázquez contributes to that tradition not by narrative but by presence.

Composition: A Profile That Breathes

The composition is a half-length, three-quarter profile rising from the lower left toward the upper right. The body’s great wedge of brown pulls diagonally across the field; the head, lifted and slightly back, counters that diagonal with an upward thrust. This simple geometry yields a sense of expectation: the saint is listening. Velázquez avoids a frontality that would turn the figure into a statue, and he avoids the devotional cliché of the ecstatic upward stare. Instead, the eyes look past us at a middle distance, the mouth parted just enough to suggest breath. The cloak’s soft pyramid settles the form on earth, while the head seems to hover in the blue like a flame.

Light as Theology

Light enters from above and to the right. It catches at the brow and nose, dissolves across the cheek, and descends into the white torrent of beard with a pearly glow. The habit drinks this light, returning it as a murmur of warm reflections. Nothing is theatrical; everything is daylike and credible. In a painting devoted to the founder of Christian monasticism, light is doctrine: grace arriving without spectacle. Velázquez gives us sanctity that is not superimposed but revealed, a lumen that clarifies rather than overwhelms. The soft aura around the head is not a badge but a phenomenon of seeing, as if the very act of attention were generating radiance.

Color: A Monastic Harmony

The palette is ascetic and resonant. A continuum of earths—umber, raw sienna, and warm gray—structures habit and flesh. Against these warms, a cool, weathered blue composes the space behind the figure. The blue is not uniform; subtle swirls and scumbles allow warmer undertones to breathe through, creating optical vibration that keeps the background from behaving like a wall. The beard’s whites are mixed with gray and faint ochre so they remain luminous without harshness. Nothing in the picture shouts. The color harmony performs the virtue it depicts: stability without dullness, humility without poverty.

Drawing with Paint: The Architecture of the Head

Velázquez models the head not with lines but with planes of tone sliding over bone. The temple is a transparent veil of pink-gray; the furrow above the brow is a gentle valley that collects shadow; the ridge of the nose catches the highest light; the cheek breaks subtly from frontal plane to profile; the ear, half consumed by the beard’s storm, remains exact. Each passage is so efficiently placed that one can read anatomy in the simplest transitions. This is the painter’s classic economy: he lets the eye complete what the brush only proposes. The effect is life rather than illustration.

The Habit as Landscape

The monk’s habit is treated as a living terrain. Its folds are not busy; they are large, geological. A broad plane rolls down from shoulder to chest, broken by a single darker crease that swerves like a ravine. The hood, nested between shoulder and neck, provides a compact shadow cave. Velázquez places a few narrow accents where fabric turns sharply—at the edge near the breast, along the descending fold at the flank—and leaves the rest to float in soft gradation. We sense the cloth’s rough nap and the weight that draws it downward. The garment thus becomes a world: stable ground from which the head rises toward contemplation.

The Beard: Motion and Gravity

St. Anthony’s beard is a torrent caught mid-fall. Velázquez paints it with a mixture of long, fluid strokes and small, broken touches that suggest both hair’s filament and its weight. Highlights settle on the beard like dew, not as chromium glare. The modeling is careful enough to persuade but free enough to breathe; you can feel air move through the strands as the saint turns his head. Baroque painters often used hair to dramatize movement; Velázquez uses it to dramatize stillness full of life.

Psychology Without Anecdote

There is no story here—no demon tempting, no gift of the desert bread, no healing of the sick. Yet the face tells a narrative of character. The upward tilt indicates aspiration; the relaxed mouth signals humility rather than strain; the eyes, neither ecstatic nor blank, hold the steady focus of a mind trained by long habit to return to the same object: God. The shallow furrows on the forehead and the weathering of the cheekbones speak of age, but not of fatigue. The painting’s most moving achievement is this balance: the body is old; the attention is young.

The Aura as Optical Event

The halo effect around the head is one of the canvas’s marvels. Rather than draw a crisp ring, Velázquez creates a nimbus by letting light values bloom into the surrounding blue. One can see thin veils of warmer paint feathered into the cool background, producing a glow that seems to be air rather than emblem. The device is painterly and metaphysical at once. It honors tradition while insisting on perception: the sacred happens in the very medium through which we see.

Comparison with Velázquez’s Other Devotional Works

Placed beside the “Christ on the Cross,” this saint shares the same devotion to unadorned truth. In the crucifixion, the body hangs against a deep black; here, the hermit rises against a cool blue. Both images strip away narrative to encounter presence directly. Compare, too, the painter’s earlier “St. Antony the Abbot and St. Paul the First Hermit” where landscape and angels occupy a busy stage. The present canvas is the other pole of Velázquez’s religious range: quiet, almost abstract, content to let a single face bear the weight of doctrine.

The Spanish Taste for Gravity

Seventeenth-century Spain loved black and brown, fabrics that consumed light and signified moral seriousness. Velázquez activates that taste while preventing monotony. His browns are layered with transparent glazes that let undercolors glow; his darkest notes are not dead but saturated. The result is an image faithful to Spanish sobriety and yet open, breathing, humane. This visual gravity suits the subject’s theology. The saint’s renunciation is not bleakness; it is clarity.

The Viewer’s Position and Devotional Use

We meet St. Anthony at a respectful proximity, lower than eye level. The vantage invites upward attention, but not worship of picture. One can imagine this canvas hanging in a side chapel or private oratory where the viewer’s daily glance would find, not sensational episode, but a partner for silent prayer. The picture teaches how to look: still the body, soften the mouth, receive the light that arrives from outside oneself. In an age of loud persuasion, the image argues for quiet consent.

Brushwork and the Ethics of Sufficiency

Velázquez’s brush never overstates. The background is a thin scumble, the habit broader and more opaque, the head the most worked yet still open. Where another painter would chase every hair, Velázquez trusts a few strokes to trigger recognition. This ethic of sufficiency—giving exactly as much information as truth requires—has moral resonance in a devotional subject. The saint has relinquished excess; the painter has too. The viewer is drawn into the same discipline, finishing forms optically, participating in the making of presence.

Iconography Reduced to Essence

Traditional attributes of St. Anthony include the tau-shaped staff, bell, book, and pig, each bearing theological freight: the T for the cross and healing, the bell for monastic summons, the book for scripture, the pig for charity toward the sick. Velázquez omits them all. Far from impoverishing meaning, the omission clarifies it. The essence of Anthony’s sanctity is not the inventory of signs but the habit of attention turned Godward. By letting the head—seat of intellect and will—carry the symbolism, the painter gives us iconography refined to first principles.

Time and the Trace of the Desert

The saint’s skin is time made visible. Cheek and temple carry small abrasions of age; hairline thins; beard whitens into chalky weight. But the flesh retains warmth; the ear glows faintly where blood thins the skin. Velázquez calibrates these signs of duration with extraordinary tact. There is no morbidity. The desert—its wind, its dryness, its endurance—has passed through the body and left character without erasing life.

A Theology of the Senses

Baroque Catholicism often emphasized the senses as channels of grace. In this painting the senses are present in chastened form: the ear open beneath thin hair, the eyes lifted, the mouth quietly parted, the nose catching light. Each sense organ appears not as appetite but as receptivity. The saint is not grasping at the world; he is receiving it. The painter, master of observation, sanctifies looking itself.

Modernity in the Absence of Stagecraft

If one stripped the title and habit from the image, it would still be a modern study in human attention. That is why the painting continues to persuade viewers far removed from Anthony’s world. Velázquez anticipated a later aesthetic that prizes candid presence over theatrical narrative. The saint is not an actor in costume; he is a person before light. In this respect the canvas shares DNA with Velázquez’s portraits of philosophers and jesters set against undefined grounds: a republic of faces where air, not architecture, is the medium of dignity.

Conservation of Grace in a Limited Palette

Economy of color often multiplies effect. With brown, blue, white, and the flesh scale in between, Velázquez achieves a symphony. The blue is not merely background; it cools the lights in the beard and collar. The brown is not merely garment; it warms the shadow of the neck and tailors the edge where flesh meets cloth. The whites are not merely highlights; they breathe in different temperatures, from cool glints on hair to warmer swells at the cheek. The harmony is so subtle that it becomes a metaphor for spiritual life: a few things, well tended, suffice.

Why This Image Endures

The endurance of “St. Anthony Abbot” rests on the painter’s refusal to confuse devotion with decoration. Velázquez removes everything that does not serve attention. He models a way of looking—calm, exact, free of exaggeration—that returns the viewer to himself refined. The saint is not all fire; he is a steady ember. The painting’s beauty is thus an ethics: be simple, be attentive, be real.

Conclusion: Sanctity Made Visible, Breath by Breath

Velázquez gives us no miracle but the miracle of seeing truly. A man in a brown habit turns toward light; beard, brow, and eye register the meeting. The air glows around his head not because of gold leaf, but because paint handled with love can make radiance. The whole canvas is an act of reverence for the ordinary means by which grace arrives—light on skin, breath in chest, cloth on shoulder, a mind lifted. In this austere, generous image, the painter of kings reveals himself as a painter of souls.