Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

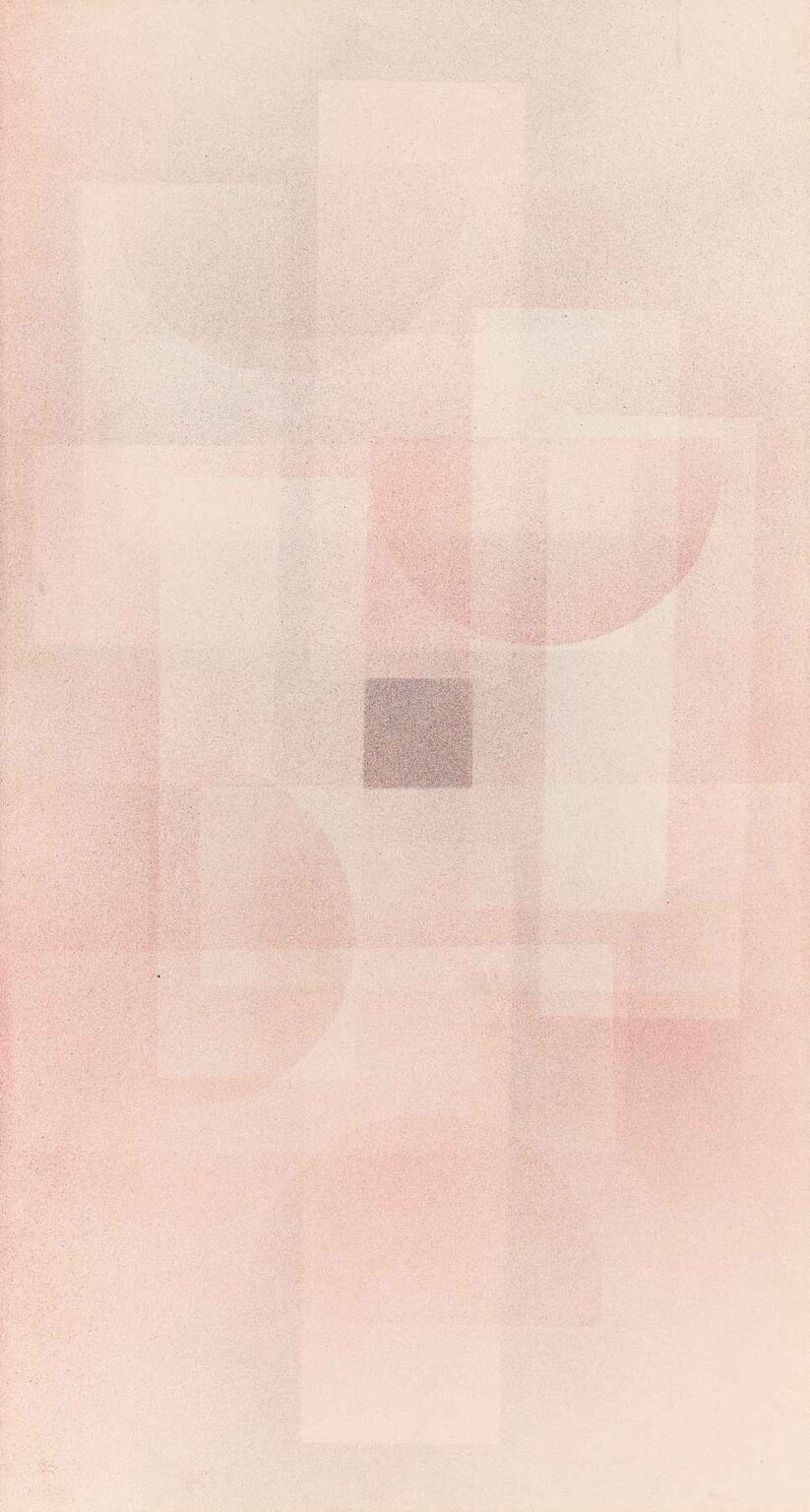

Wassily Kandinsky’s Square in the Fog (1932) stands as one of the most enigmatic works of his late period, when the artist was both consolidating his lifelong theoretical explorations and responding to the shifting cultural landscape of pre‑war Europe. In this composition, Kandinsky abandons the bold, sharply defined geometric forms of his earlier Bauhaus years in favor of a more atmospheric, almost ethereal approach. Soft-edged squares, circles, and rectangles drift in and out of view, as though glimpsed through a veil of mist. The painting becomes a meditation on the interplay of form and emptiness, presence and absence, color and silence.

Over nearly two thousand words, this analysis will examine the historical and biographical context of Square in the Fog, unpack the theoretical underpinnings drawn from Kandinsky’s writings such as Point and Line to Plane, conduct a detailed formal analysis of its composition, explore its technique and materiality, consider the symbolism and spiritual resonance embedded within its haze, situate it within Kandinsky’s broader oeuvre, and assess its enduring legacy in the canon of modern abstract art.

Historical Context of 1932

By 1932, Europe was undergoing profound social and political upheaval. The Weimar Republic in Germany was fracturing under the onslaught of economic depression and rising extremist parties. Kandinsky himself, having been appointed to the Bauhaus faculty in 1922 by founder Walter Gropius, had spent a decade teaching and experimenting in Dessau and Berlin. The Bauhaus, founded on the principle of uniting art, craft, and technology, encouraged its faculty to explore the synthesis of form and function. Kandinsky’s own theoretical treatise, Point and Line to Plane (1926), codified this Bauhaus spirit, setting forth a systematic language of abstraction.

Yet in 1932, the Bauhaus faced mounting political pressure, forcing its closure a year later. Kandinsky, anticipating these dire shifts, began planning his departure for Paris, which he would make permanent in 1933. Square in the Fog emerges at this juncture of transition: the confidences of the 1920s give way to a more introspective mode. The dense social atmosphere, the threat of censorship, and Kandinsky’s personal decision to leave Germany all converged to shape this late work’s introspective tone.

Kandinsky’s Theoretical Framework

Kandinsky’s writings remain a crucial lens for understanding Square in the Fog. In On the Spiritual in Art (1911), he argued that color and form carry emotional and spiritual vibrations independent of representational content. Later, in Point and Line to Plane, he codified how points, lines, and planes could be combined to produce dynamic compositions. He delineated how geometric shapes—circles for mellowness, squares for sobriety, triangles for dynamic tension—could be orchestrated like musical notes.

By the 1930s, Kandinsky had internalized these principles to such an extent that his compositions no longer needed sharply defined forms to convey their impact. Instead, he began to explore how shapes could dissolve into one another, how color fields might overlap to create new, intermediate tones, and how negative space could function as an active, generative element. Square in the Fog thus represents the culmination of Kandinsky’s decades‑long investigation into synesthesia: the visual counterpart of a gentle lullaby, where motifs float and recede, inviting a contemplative state akin to meditation.

Formal Analysis: Composition and Structure

At first glance, Square in the Fog appears deceptively simple: a cluster of pale, overlapping rectangles and circles rendered in washed‑out pinks, creams, and grays against an off‑white ground. But beneath this apparent simplicity lies a complex choreography of form. The central square, slightly off‑center, serves as an anchor—a discreet stabilizing force around which the other shapes revolve. Its edges are softly broken, as though eroded by the surrounding mist, suggesting impermanence.

Surrounding the square are larger, semi‑transparent rectangles that recede in tonal value. Their translucency allows colors to mix optically where they overlap, producing gentle gradients rather than abrupt shifts. Interspersed among them are faint half‑circles and partial arcs, their curves counterbalancing the rectilinear geometry. This interplay of straight edges and soft curves generates a subtle tension: the eye glides along the arcs, then comes to rest against the quieter planes.

Vertical and horizontal axes are implied rather than explicitly drawn. The slightly off‑kilter alignment of shapes gives the composition a gentle sway, as though observing them from a slight angle or through shifting fog. There is no clear perspective or vanishing point. Instead, the spatial depth arises through tonal layering: the palest shapes seem to float furthest back, while the more saturated pinks hover nearer the surface.

A pivotal feature is the painting’s use of empty space. Rather than crowd the canvas, Kandinsky leaves generous areas of untouched ground. These voids act as visual “breaths,” allowing the forms to assert themselves without overwhelming the viewer. In Kandinsky’s spiritual vocabulary, these pauses equate to silences in music—moments that give meaning and impact to the notes that come before and after.

Color Harmony and Emotional Resonance

Kandinsky’s mastery of color theory is evident in the nuanced palette of Square in the Fog. His choice of pinks—a color range he associated with soothing warmth and gentle optimism—imbues the painting with an introspective calm. Subtle touches of gray and taupe introduce cool shadows, preventing the work from feeling overly sweet or maudlin.

Where shapes overlap, Kandinsky allows the colors to interpenetrate, creating new intermediate hues: dusty rose, warm ochre, and muted lavender. These mixed tones reinforce the overall sense of unity: no single hue dominates. Instead, all colors exist in a state of poised equilibrium. The resulting emotional impression is one of serene melancholy—a wistful longing that refuses to tip into despair.

In his later writings, Kandinsky described the psychological effects of colors, attributing to each hue a distinct vibration on the human psyche. Square in the Fog offers a case study in these theories: the gentle pinks encourage inward reflection, the grays suggest sober contemplation, and the interplay yields a gentle reassurance that even amidst uncertainty, harmony can be found.

Technique and Materiality

Executed in watercolor and gouache on paper—a medium Kandinsky favored for its immediacy—Square in the Fog reveals traces of the artist’s hand. The subtle granulation of pigments, the soft gradients achieved through wet‑on‑wet washes, and the occasional edge where the brush pulled pigment to a fine line all testify to a practiced control. Kandinsky allowed slight irregularities—tiny blooms where water pooled, delicate crusts where pigment dried—to remain visible. Rather than smoothing them away, he embraced these serendipitous effects as evidence of nature’s unpredictability.

The choice of paper also contributes to the work’s atmosphere. Its natural warmth interacts with the translucent washes, allowing the ground to glow through. The texture—visible as a faint tooth—catches pigment in certain areas, adding a tactile dimension to the visual experience. Unlike his crisp Bauhaus works, where edges were immaculate, here Kandinsky permits softness and wear, reinforcing the painting’s dreamlike quality.

Symbolism and Spiritual Meaning

Kandinsky believed that abstract forms could serve as spiritual signifiers, capable of conveying universal truths beyond linguistic barriers. The square, for him, represented the earthly realm—stability, structure, and the tangible world. Yet in Square in the Fog, the square is not a monolith but a fragile shape dissolved by haze. This suggests that earthly certainties are always subject to transformation, that stability arises only fleetingly within the flux of existence.

The surrounding fog—implied rather than explicitly painted—acts as a veil between the material and the ethereal. It recalls Kandinsky’s fascination with theosophy and Eastern philosophy, both of which influenced his concept of art as a portal to higher realms. The painting’s muted palette and diffused light evoke a dawn mist or the pre‑dawn “blue hour,” moments when the boundary between night and day dissolves. In this liminal zone, ordinary perceptions shift, and the soul becomes receptive to deeper vibrations.

Viewed through this lens, Square in the Fog transcends mere formal experiment. It becomes a visual mantra, inviting introspection and spiritual attunement. Each overlapping plane and softness of edge whispers the principle of interdependence, reminding viewers that form and formlessness, presence and absence, are interwoven aspects of reality.

Relationship to Kandinsky’s Oeuvre

While Kandinsky’s early works brimmed with bold color contrasts and jagged geometry—celebrated examples being Composition VIII (1923) and his pioneering Improvisations—Square in the Fog belongs to a more introspective late phase. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Kandinsky alternated between crystalline pure-geometry paintings and quieter tonal abstractions on paper. Square in the Fog epitomizes this quieter strand, free from the doctrinaire Bauhaus rectitude yet still bearing the imprint of his geometric rigor.

In comparison to his 1930 watercolors—often titled Bauhauswasserfarben—this work shares the soft luminosity but advances a subtler integration of form. Shapes no longer sit side by side; they merge and interact in a single atmospheric field. This evolution points toward Kandinsky’s final phase in Paris, where his forms would become ever more delicate before his passing in 1944.

Influence and Legacy

Although overshadowed by Kandinsky’s large oil masterpieces, Square in the Fog has inspired generations of artists exploring the boundaries between geometry and atmosphere. Its delicate layering anticipated post‑war color field painters and the lyrical abstractions of the 1960s. Contemporary digital artists, too, reference its soft overlaps and tonal translucencies in UI designs and generative art.

Moreover, the painting’s spiritual charge continues to resonate in a world increasingly inundated by noise. Its gentle invitation to slow down, to appreciate the spaces between shapes as much as the shapes themselves, offers a counterpoint to the perpetual bustle of modern life. In mindfulness and meditation circles, reproductions of Square in the Fog serve as visual aids, guiding practitioners into states of calm openness.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Square in the Fog (1932) represents both a culmination and a transformation of his lifelong pursuit of spiritual abstraction. Emerging from the turmoil of pre‑war Europe and the impending closure of the Bauhaus, this work dissolves rigid geometry into atmosphere, forging a new mode of abstraction that prioritizes mood, translucency, and inner resonance. Through its soft color harmonies, diffused edges, and contemplative voids, the painting achieves a poetic balance between form and formlessness.

In the nearly ninety years since its creation, Square in the Fog has quietly exerted its influence across painting, design, and spiritual practice. It endures as a reminder that even within abstraction’s most refined geometries, art’s highest calling remains the evocation of inner truths and the opening of the soul to unseen harmonies.