Image source: artvee.com

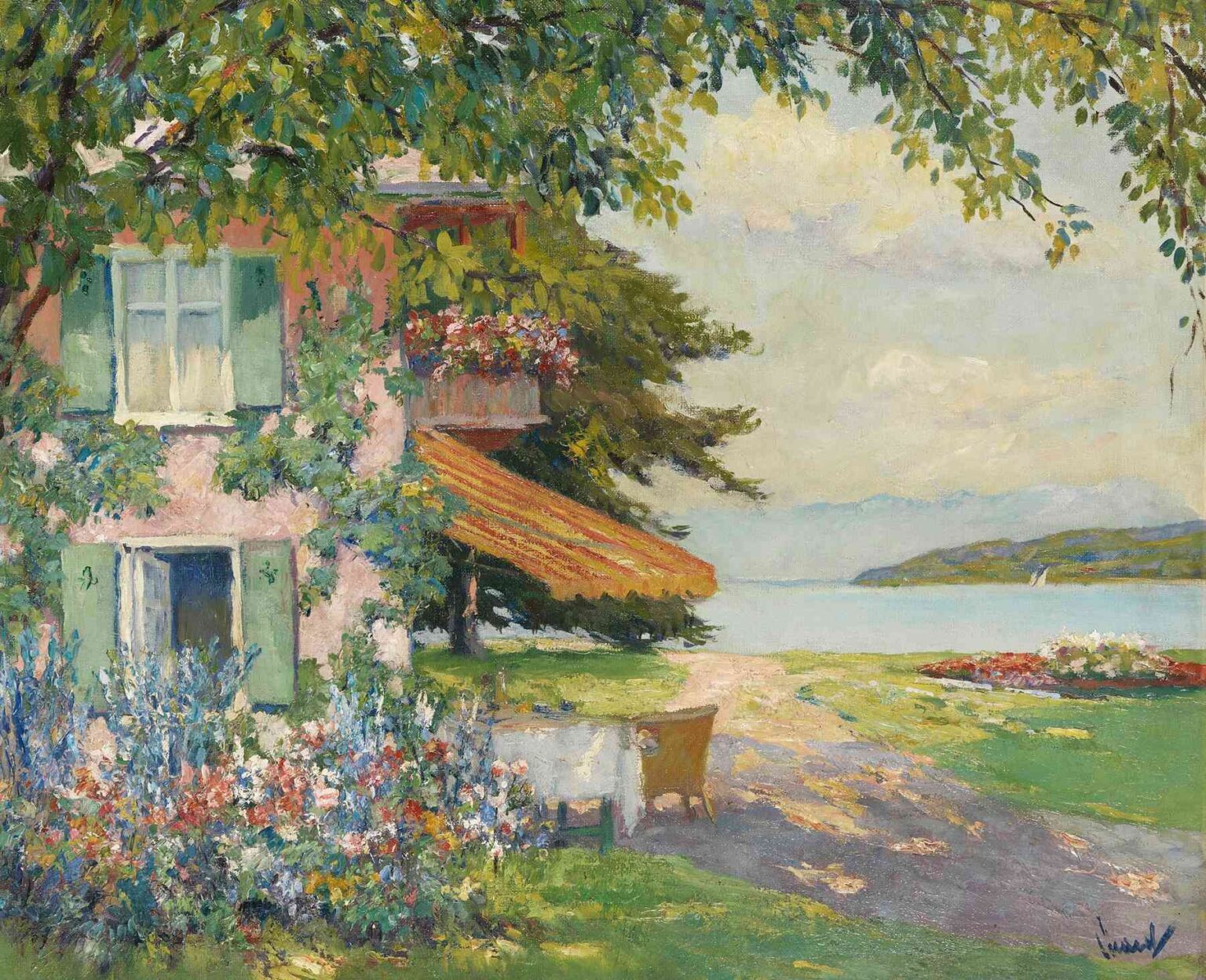

Edward Cucuel’s “Spring Garden in Starnberg” (1920) is a luminous and emotionally uplifting landscape that captures the essence of early 20th-century European plein air painting. With its riotous spring blossoms, dappled sunlight, and serene lakeside setting, the painting is a testament to Cucuel’s talent for merging Impressionist brushwork with a refined sense of atmosphere and harmony. In this artwork, Cucuel distills a perfect moment—a warm afternoon where nature, architecture, and leisure converge into a symphony of light and tranquility.

Painted during Cucuel’s mature period in Germany, “Spring Garden in Starnberg” depicts a charming garden scene by Lake Starnberg, one of Bavaria’s most celebrated lakes, near Munich. The work is imbued with freshness, optimism, and a sense of gentle domesticity. The composition balances floral abundance with open space, and the painter’s light-drenched palette evokes the sensation of a cool breeze brushing through sunlit leaves. As an American expatriate who became deeply entwined with German art circles, Cucuel brings an international flair to his interpretation of Bavarian serenity.

This analysis will explore the historical background of the painting, dissect its compositional structure, interpret its symbolism and thematic content, and position it within both Cucuel’s personal style and the broader movements of Impressionism and post-Romantic landscape painting.

Historical and Biographical Context

Edward Cucuel (1875–1954) was born in San Francisco but trained extensively in Paris and Munich. He became a leading figure in the German Impressionist movement, often associated with the “Munich Secession” and the broader European “plein air” tradition. His style blends French Impressionist colorism with the compositional clarity of German Romanticism.

By 1920, Cucuel had already established himself as a master of light and leisure. He frequently painted scenes featuring women in garden settings, riverbanks, and lakeside retreats. Lake Starnberg, just south of Munich, was a favorite subject for Cucuel and other artists of the time. Its crystal waters, surrounded by the Bavarian Alps, provided a perfect muse for painters seeking to capture moments of unspoiled nature and bourgeois tranquility.

In the aftermath of World War I, Cucuel’s vision of peaceful beauty offered visual comfort and a yearning for pre-war elegance. “Spring Garden in Starnberg” can be interpreted not only as an aesthetic celebration but also as an emotional balm—an idealized image of peace and domestic joy.

Compositional Structure and Formal Analysis

The composition of “Spring Garden in Starnberg” is a masterclass in balance and perspective. On the left, a stucco garden house with green shutters rises vertically and is framed by flowering bushes in full bloom. Ivy and vines crawl along the façade, integrating the building with its natural environment. An orange-striped awning extends outward from the second story, guiding the eye horizontally toward the lake on the right side of the canvas.

This visual transition—from vertical house to horizontal waterline—is orchestrated with painterly grace. The lake itself, placid and silvery-blue, stretches into the distance, interrupted only by the distant silhouettes of low hills and a sailboat drifting serenely in the background. A narrow dirt path, cast with shadows and soft sunlight, leads the viewer’s gaze from the bottom right corner toward the distant water, acting as a psychological invitation to step into the scene.

In the foreground, a simple table and wicker chair are set up beneath the awning, suggesting recent human presence. The tablecloth is casually draped, and the empty chair implies a temporary pause in activity—a moment of rest or quiet contemplation. The presence of this furniture lends the scene intimacy and immediacy.

Above all, the painting’s compositional strength lies in its framing. Overhanging tree branches form a leafy canopy at the top of the canvas, creating a natural vignette that encloses the entire scene. This technique, borrowed from Japanese prints and practiced by French Impressionists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, deepens the sense of depth and shelter within the landscape.

Color and Light

Cucuel’s palette in “Spring Garden in Starnberg” is characterized by lush greens, soft pastels, warm ochres, and cool blues. These colors are applied with visible, spontaneous brushstrokes, enhancing the textural vitality of the canvas. The treatment of foliage is particularly notable—layers of green range from emerald to olive to chartreuse, capturing the full spectrum of spring vegetation under sunlight.

The house’s pinkish façade glows with a sun-washed radiance, contrasting gently with the viridescent shadows cast by the trees. Cucuel’s use of sunlight is not harsh or direct; rather, it is diffused, filtered through foliage, and rendered in strokes of yellow and pale gold. The orange of the awning and the flowers on the balcony provide visual punctuation—warm accents that complement the scene without overwhelming its subtlety.

The water of Lake Starnberg is painted in tranquil tones—silvery blues and pale greens—that reflect the calm sky above. Clouds drift softly in the distance, their creamy highlights reinforcing the feeling of a gentle spring day. This treatment of light and color draws direct influence from Impressionism, yet it is tempered by a compositional logic and attention to detail that is distinctly German.

Symbolism and Thematic Elements

At its core, “Spring Garden in Starnberg” is a painting about harmony—between nature and architecture, solitude and society, human creation and organic growth. It exemplifies the turn-of-the-century ideal of Lebensreform, or “life reform,” which promoted a return to nature, healthy living, and aesthetic beauty in response to industrialization and urban chaos.

The flowers blooming around the house symbolize fertility, renewal, and domestic happiness. Their profusion suggests abundance not just of plant life, but of emotional richness. The inclusion of the balcony adorned with flowerpots and the awning extended for shade reinforces the idea of cultivated nature—beauty that has been harmoniously integrated with human needs.

The path that leads toward the water suggests personal reflection or journey. The viewer is invited to imagine walking down that path toward the stillness of the lake, which becomes a metaphor for contemplation and transcendence. The solitary sailboat in the distance may symbolize freedom, escape, or a romantic ideal of individual exploration.

Meanwhile, the presence of the wicker chair and covered table implies a quiet domestic life—a private world where one can read, paint, sip tea, or converse with loved ones. This quiet celebration of middle-class leisure, a hallmark of Impressionist painting, becomes in Cucuel’s hands something deeper: a reaffirmation of human dignity and peace.

The Role of Nature and Domesticity

Unlike many 19th-century landscape painters who emphasized sublime or dramatic views, Cucuel focused on “domesticated” nature—gardens, riverbanks, lakesides, and cozy retreats. In “Spring Garden in Starnberg,” nature is not overwhelming; it is welcoming, gently framing human activity without overpowering it. This approach reflects the shift from Romantic awe to Impressionist intimacy.

Nature in this painting acts as both subject and character. The trees, flowers, and lake are rendered with such tactile softness that they seem almost animate. They invite touch, movement, and presence. The overhanging leaves at the top of the canvas act like a curtain, reinforcing the theatricality of the scene—as if we are looking into a private performance of life at its most beautiful and untroubled.

Cucuel’s emphasis on domesticity is central to his broader body of work. Many of his paintings feature women reading, reclining, or strolling in similar settings. While there are no visible figures in “Spring Garden in Starnberg”, their presence is implied—through the setting, the furniture, and the mood. This omission allows the viewer to insert themselves into the scene, deepening the painting’s psychological resonance.

Technique and Brushwork

Cucuel employs a loose, impressionistic brushstroke that captures the fleeting qualities of light and movement. His foliage is rendered with broken color, a technique pioneered by Monet and Renoir, which mimics the shifting play of sunlight through leaves. The brushwork is more gestural in the flowers and trees, while more controlled and linear in architectural elements like the house’s shutters and balcony.

The paint is applied in thin layers, allowing the texture of the canvas to show through in places, contributing to the overall lightness and transparency of the image. This approach avoids the heavy varnishing or impasto typical of academic painting, instead favoring luminosity and breathability.

What sets Cucuel apart from many of his contemporaries is his ability to blend this impressionistic spontaneity with compositional rigor. The scene is organic, but never chaotic. Every element—from the placement of the awning to the direction of the path—guides the eye gently through the frame.

Comparative and Cultural Influences

Cucuel’s painting bears clear echoes of French Impressionism, particularly the garden scenes of Claude Monet and the domestic tranquility of Pierre-Auguste Renoir. However, his style also reflects the German affinity for structure and narrative. Unlike Monet, who often omitted architectural detail in favor of color fields, Cucuel preserves the form and function of the house, making it a central anchor in the painting’s visual story.

There are also parallels with the Scandinavian painter Carl Larsson, who similarly celebrated the integration of home and garden, often with a focus on light, peace, and artistic domesticity. In this way, “Spring Garden in Starnberg” joins a larger European tradition of celebrating bourgeois harmony, cultivated nature, and the rituals of peaceful life.

Culturally, the painting captures a distinctly post-war yearning for normalcy and optimism. In 1920, Europe was emerging from the devastation of World War I. This return to tranquil garden scenes may reflect a collective desire to heal, rebuild, and rediscover beauty in everyday existence.

Conclusion: An Invitation to Peace and Beauty

Edward Cucuel’s “Spring Garden in Starnberg” is more than a charming lakeside scene. It is a visual hymn to life’s gentle rhythms—a meditation on nature’s elegance, domestic joy, and the enduring appeal of quiet beauty. With its careful composition, radiant light, and serene atmosphere, the painting invites viewers not just to look, but to linger, to breathe, and to imagine themselves within its embrace.

As both an artistic achievement and a cultural artifact, the work exemplifies the power of art to offer solace, inspiration, and timeless pleasure. It remains one of Cucuel’s most eloquent affirmations of the bond between people and the natural world—a bond rooted in light, color, and the spirit of spring.