Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

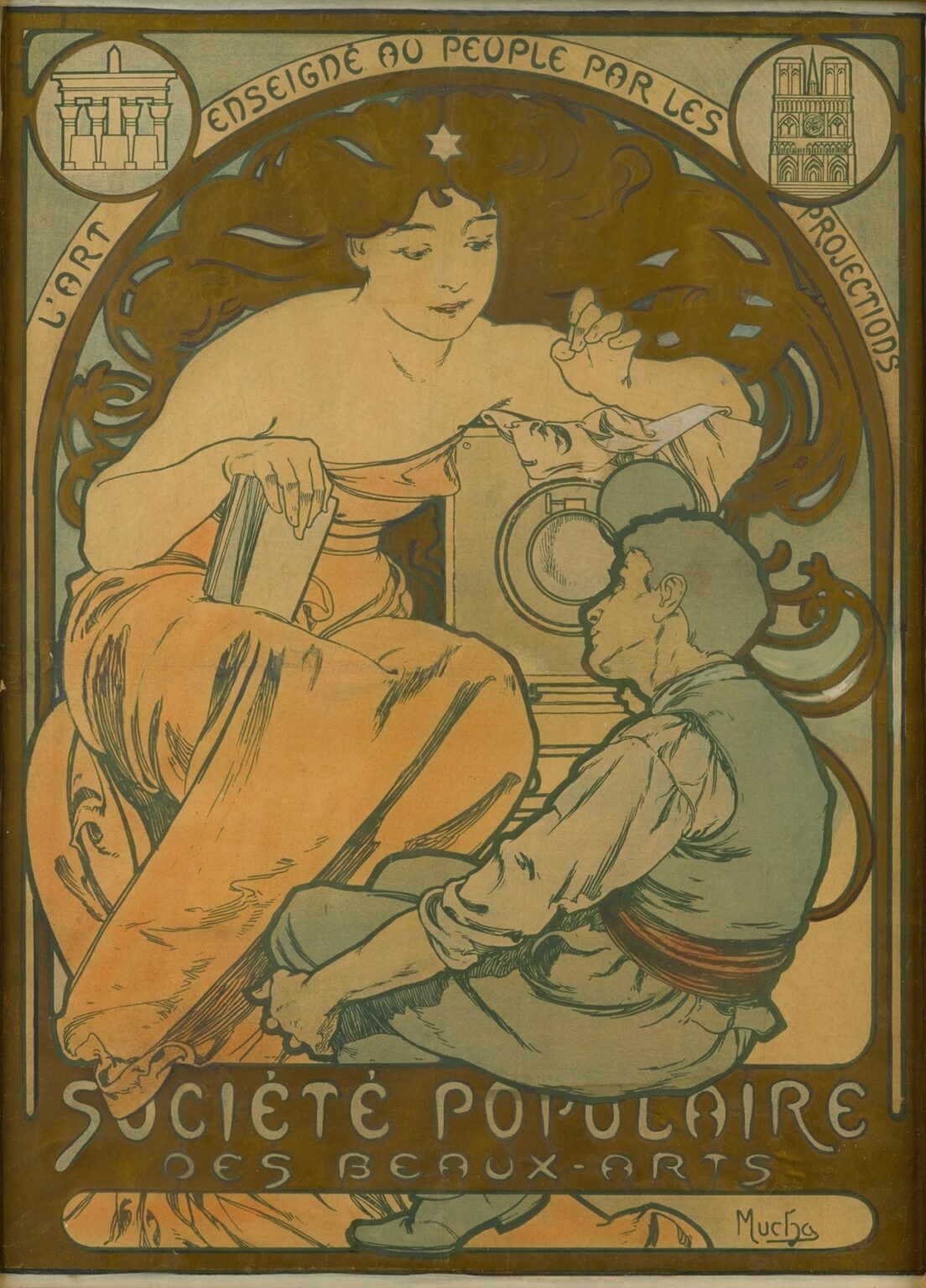

Alphonse Mucha’s 1897 poster for the Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts exemplifies the artist’s peak mastery of Art Nouveau aesthetics and visual rhetoric. Commissioned to promote an organization dedicated to democratizing access to the fine arts, the poster weds allegory, ornamental linework, and a refined palette to convey a bold cultural program: “L’Art enseigne au peuple par les projections.” This image celebrates the Société’s use of projected lantern slides to teach art history and appreciation to audiences across France. Through a harmonious fusion of figure, text, and decorative framing, Mucha transforms a commercial commission into a poetic manifesto—one that continues to inspire designers and art enthusiasts more than a century later.

Historical Context and the Société’s Mission

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, Paris’s cultural landscape brimmed with institutions championing artistic education and public engagement. Founded in 1895, the Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts sought to supplement formal academies by offering touring lantern-slide lectures on painting, sculpture, and architecture. Utilizing the latest projection technology, itinerant lecturers brought visual masterpieces into community halls and cafés, enabling workers and rural audiences to experience the grandeur of national galleries. Mucha’s poster appeared at a moment when popular education movements aligned with democratic ideals, and technological innovations were reshaping public culture. His design not only advertised upcoming lectures but also visually embodied the Société’s belief that art could uplift and unite the citizenry.

Commission and Collaboration

When the Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts approached Mucha in 1897, they needed an image that would communicate the novelty and gravitas of their educational projections. Mucha, already in high demand for his Sarah Bernhardt posters and commercial lithographs, embraced the challenge. He visited projection halls and studied lantern-slide equipment to render the apparatus authentically. Collaborating closely with the Imprimerie Champenois in Paris, he translated his full-scale gouache study into a multi-stone lithograph, specifying colors and registration marks to ensure fidelity. The printed poster was distributed to municipal halls, newsstands, and educational centers, where its distinctive Art Nouveau style instantly conveyed both artistic prestige and forward-looking pedagogy.

Composition and Spatial Design

Mucha organizes the poster within an elegantly proportioned rectangular frame whose corners curve softly inward. The top region houses two circular vignettes: on the left, a classical columned portico representing the École des Beaux-Arts or national museum; on the right, the façade of Notre-Dame symbolizing monuments of French cultural patrimony. Between these, an arched banner bears the slogan “L’Art enseigne au peuple par les projections.” Dominating the central field, a seated female allegory of Art guides a kneeling boy who gazes upward, mask in hand, before a projection machine. The lower third of the poster contains the bold title “Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts” rendered in a custom Art Nouveau typeface. Mucha balances these elements so that the viewer’s eye flows from the emblematic landmarks above, through the central narrative scene, and finally to the Société’s name—creating a seamless visual journey.

The Allegorical Figures

At the heart of the composition lies an idealized female figure representing Art or the Muse, her long hair flowing in stylized waves that fill the background like a living tapestry. A small star adorns her forehead, signifying enlightenment and creative inspiration. Draped in softly pleated robes, she cradles a book in one hand—symbolizing knowledge—and extends the other to present a theatrical mask to a rapt youth. The boy, clad in simple peasant attire, kneels before her in awe as he holds the blank mask aloft, ready to receive projected images of plaster casts or famous paintings. This interaction dramatizes the transfer of cultural heritage from the guardians of high art to the eager populace, captured in the intimate gesture between teacher and student.

Symbolism and Iconographic Motifs

Mucha weaves multiple layers of symbolism into the design. The projecting lantern, its lens and reels indicated with spare but precise linework behind the figures, embodies the technological means by which art is disseminated. The book at the Muse’s side connotes the theoretical foundations of art history, while the mask alludes to theater, drama, and the performative aspect of public lectures. The circular vignettes reference France’s architectural jewels, reminding viewers that the projected images will include not only canvases but also monuments of national identity. The flowing hair and robes merge with decorative swirls of the backdrop, suggesting that art itself is a dynamic, living force enveloping and transforming the viewer.

Mastery of Line and Ornamental Integration

Central to Mucha’s artistry is his command of the calligraphic line. The contours defining the Muse’s drapery, the boy’s clothing, and the projection machine are rendered with continuous strokes that swell and taper to convey volume and movement. The background features tightly controlled scrollwork that mirrors the whorls of the figures’ hair and the marquee frame. Even the subtle patterning on the projection lens and the decorative border at the poster’s edge emerge from the same graphic vocabulary. Mucha’s modulation of line weight ensures clarity at a distance while rewarding close inspection with intricate filigree—attesting to the dual purpose of attracting attention and sustaining engagement.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha employs a refined three-ink palette—muted olive green, warm sepia, and soft coral—against the natural ivory of the paper. The Muse’s robes glow in gentle coral hues, contrasting with the boy’s earth-toned garb and the olive shading of architectural vignettes. The subdued warmth evokes lamplight and the intimate atmosphere of projection lectures held at dusk. Achieving these effects required a multi-stone lithographic process, in which each color was applied from its own stone, carefully registered to avoid misalignment. Mucha’s meticulous color keys guided the printer in mixing transparent inks that allowed underlying layers to shimmer through, yielding subtle gradations and preserving the crispness of his linework. The result is a lithograph that feels both luminous and tactile, inviting close appreciation.

Typography as Visual Element

In “Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts,” Mucha treats lettering as an integral component of the overall design. The slogan’s curved baseline follows the arc of the vignettes, reinforcing the poster’s geometry, while its rounded capitals display slight irregularities—wider bowls, flared serifs—that echo the organic flow of the decorative lines. The main title at the bottom employs high-contrast letterforms whose vertical strokes find harmony with the projection machine’s cylindrical silhouette. Even the publisher’s imprint appears in a condensed serif that complements the primary type without competing for attention. Mucha’s typographic choices ensure that text and image exist in a unified visual language, rather than separate communicative layers.

Framing and Decorative Borders

Surrounding the central scene, Mucha integrates slender decorative bands that serve both as frame and ornament. A narrow strip of stylized leaf motifs runs along the poster’s perimeter, linking to the swirling foliage in the background behind the Muse’s hair. The circular vignettes themselves rest within medallions whose borders echo these leaf patterns. Between them, the arching slogan sits atop a band of stippled texture reminiscent of masonry. At the base, the title is flanked by scroll‐like flourishes that suggest the reel mechanism of the projector. These borders not only organize the composition but also reinforce the thematic unity between nature, art, and technology—a hallmark of Art Nouveau’s total design ideal.

Reception and Legacy

When first displayed in Parisian lecture halls and municipal venues, Mucha’s poster garnered immediate acclaim for its elegance and clarity of message. The Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts reported increased attendance to its projection lectures, in part thanks to the poster’s ability to convey the excitement and cultural prestige of the program. As the Art Nouveau movement spread across Europe, the poster was reproduced in journals and exhibited alongside Mucha’s theatrical lithographs. Its blend of allegory, typography, and modern technology influenced graphic design in Belgium, Britain, and the United States, paving the way for the golden age of illustrated advertising. Today, original prints of the poster are highly prized, housed in museum collections as exemplars of late-19th-century visual rhetoric.

Preservation and Contemporary Relevance

Original lithographs of “Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts” face the challenges of acidic paper and light sensitivity. Conservationists employ deacidification treatments and UV-filtering glazing to preserve the fragile coral and olive inks. Digitization projects have made high-resolution scans available for study, ensuring that designers and scholars can examine Mucha’s linework and color separations without endangering the originals. Contemporary educators and cultural institutions continue to draw on Mucha’s poster as a model for visual storytelling and public engagement. Its core message—that art educates and unites—resonates today in digital projection, museum outreach, and art-for-all initiatives worldwide.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Société Populaire des Beaux-Arts” poster stands as a masterful synthesis of Art Nouveau aesthetics, technological optimism, and civic idealism. Through sinuous line, a warm yet restrained palette, and integrated typography, Mucha transforms a promotional commission into an allegory of art’s power to enlighten the populace. The poster’s central interaction between the allegorical Muse and the aspiring youth poignantly captures the transfer of cultural knowledge facilitated by projection technology. More than a century after its creation, the image endures as a testament to the timeless belief that art belongs to the people—and that design itself can be a potent vehicle for education and social uplift.