Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

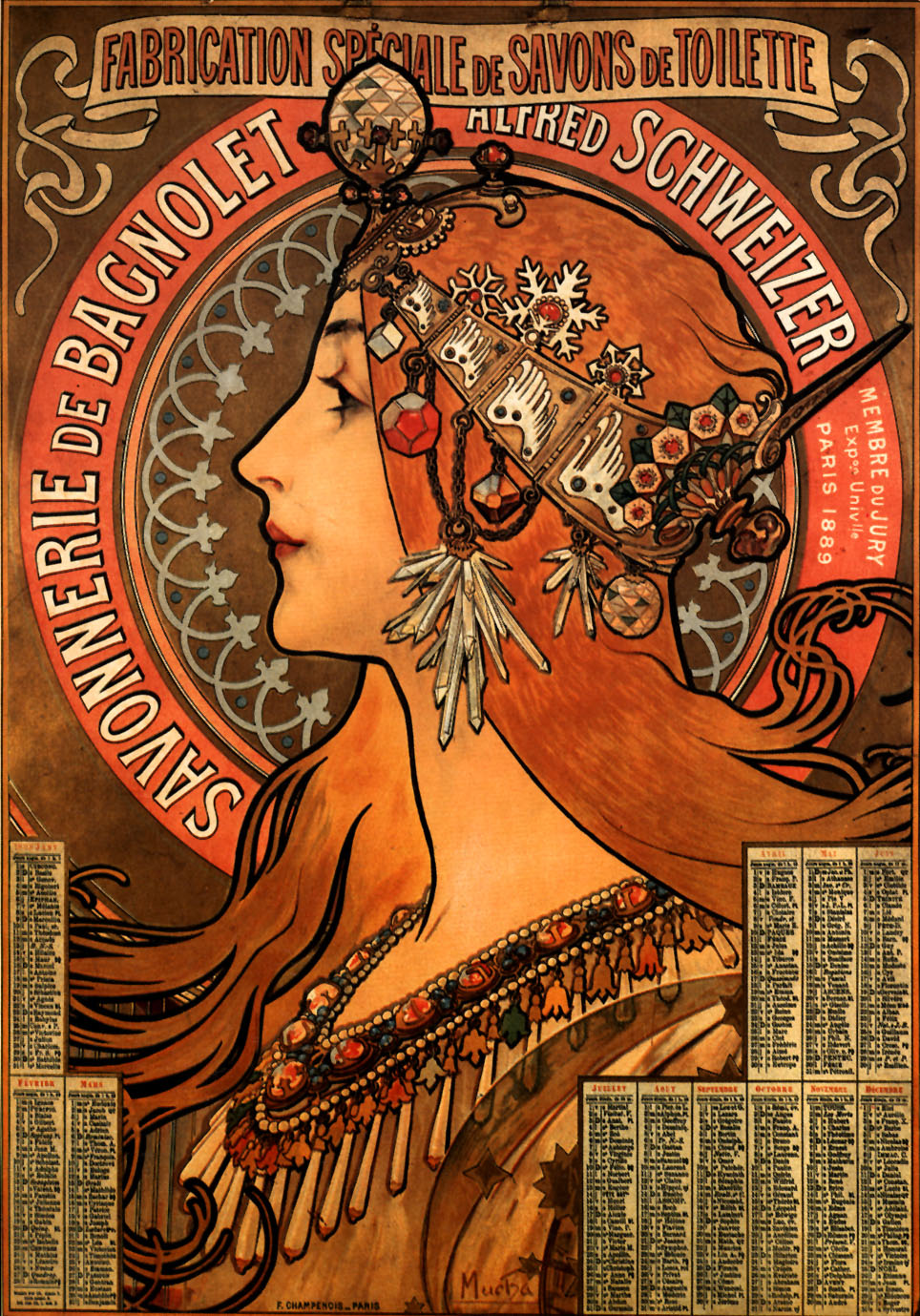

Alphonse Mucha’s “Soap Factory of Bagnolet” (1897) turns an everyday commodity into a coronation. A woman in radiant profile fills the sheet, her auburn hair flowing like perfumed smoke, her crown a small architecture of prisms, chains, and enamelled plaques. Around her head, a circular ground patterned like carved stone or stained glass doubles as halo and brand frame, while monumental lettering curves with the design to announce “Savonnerie de Bagnolet” and “Fabrication spéciale de savons de toilette.” At the bottom corners, compact columns of calendar dates convert the poster into a yearlong companion. It is advertising and ornament, utility and dream, fused into a single, persuasive image of cleanliness as luxury.

Historical Setting and Purpose

The late 1890s saw Paris awash in color lithographs that made daily life look glamorous. Mucha, already celebrated for his theatrical posters, worked with the printer F. Champenois to produce designs that integrated text, image, and ornament so thoroughly that the street itself felt curated. Soap was a perfect candidate for this treatment. It belonged to modernity’s gospel of hygiene and to the new domestic pleasures of scented toiletries. “Soap Factory of Bagnolet” does not show a factory or a bar of soap at all; instead, it sells the idea of refinement—the promise that a mundane product can confer the glow of the woman here ennobled by light, fragrance, and jewel-toned decoration.

Composition as a Crowned Profile

Mucha composes the woman’s head in strict profile, a silhouette borrowed from medals and cameos. The decision serves clarity across distance and embeds the figure within a lineage of classical dignity. The neck rises like a column to support the head; the jawline flows in a single continuous curve; the eye is gently lowered with an inward calm that suggests self-sufficiency rather than coquetry. The entire design hinges on this profile, which becomes a keystone around which text, ornament, and calendar blocks are assembled.

The Halo and Its Architecture

Behind the head, a great circular disk is subdivided into interlacing arcs and quatrefoils. It reads as a cross between Gothic tracery and a tiled rosette, and it carries several meanings at once. As halo, it sanctifies the figure. As tile or carved screen, it hints at bathrooms and the rituals of bathing. As decorative geometry, it provides a quiet, cool field against which the warm flesh and copper hair glow. The circle also acts as an engine for the layout: the letters of “Savonnerie de Bagnolet” ride its outer rim, while smaller ornaments nest in its inner band, binding language to image with architectural logic.

Lettering as Design

Mucha’s type is never an afterthought. Here the brand name bends around the circle in tall, rounded capitals that share the same rhythm as the curves of hair and jewelry. Across the top, a banner unfurls “Fabrication spéciale de savons de toilette,” its borders curling like ribboned steam. The letters are outlined in black and filled with a pale tone so they sit legibly against the background, while their red shadows echo the warm palette of hair and skin. Typography becomes architecture; the words are the masonry that frames the heroine.

The Crown and the Language of Luxury

The headdress is a small fantasy palace. Angular plaques studded with patterns line the brow; delicate chains hang down; snowflake rosettes and cut gemstones punctuate the metalwork; pendants shaped like tear drops or prisms catch imaginary light. Mucha draws each object with ornamental specificity but without the heaviness of realism; the crown remains airy, a matrix through which hair escapes. The association between soap and jewel is deliberate. It reframes cleanliness as adornment and suggests that the refined luster of cut stones is the analogue of skin after washing.

Hair as Perfume Made Visible

The hair, drawn with those signature whiplash curves, escapes the crown in tendrils that behave like a scent. It flows behind the profile and down the shoulder in ribbons of copper and auburn, lines thickening and thinning like musical phrasing. In his decorative panels Mucha often lets hair perform the emotional role of landscape; here it is the atmosphere of the brand. The silky waves carry the suggestion of fragrance, softness, and touch—qualities a bar of soap promises but cannot show.

Color and Atmosphere

The palette saturates the page with warmth: honey, terracotta, amber, and cinnamon dominate, tempered by cool silver-blues and soft grays in the halo and metalwork. This contrast gives the figure life; she glows like a candle before a stone apse. Skin tones are not high-chroma pinks but a refined apricot that projects health without gaudiness. Small accents—ruby pendants, bluish gems, olive leaves—keep the eye moving without diluting the unity. The overall effect is a golden hour inside the bathroom, a climate of pleasant heat and luminous air.

Ornament with Function

Mucha’s design does not use ornament as filler. Every motif serves a communicative task. The wing-like scrolls at the top corners steer attention inward. The lace-like edge along the necklace repeats the rhythm of bubbles without literalizing them. The halo’s geometry suggests crafted interior spaces where soap belongs. Even the little stippled highlights on gems and metal double as visual metaphors for sparkle and purity. The poster argues that beauty and function are not opposites; beauty is how function is understood.

The Calendar and the Domestic Year

At the bottom corners and along the lower edge, printed calendars list the months—an ingenious way to keep the poster in service for a full year. The practical column of dates sits comfortably within the decorative field because Mucha renders them as part of the design, framed in small ornamental cartouches that echo the geometry above. The brand thus occupies not only the wall but time itself; the soap’s name shares the rhythms of the household year, a brilliant fusion of advertising and usefulness.

The Social Promise of Cleanliness

Nineteenth-century Paris linked hygiene with civic virtue and modern life. Running water, commercial toiletries, and public baths were symbols of progress. “Soap Factory of Bagnolet” aligns the brand with this ethos, but with a gentleness absent from many hygienic campaigns. There is no scolding reminder of germs, no laboratory bottle. Instead, cleanliness becomes pleasure and dignity, a transformation from ordinary to luminous. The woman is not a consumer caricature; she is a personification of an ideal—cultivated, calm, and empowered by ritual care.

The Viewer’s Path through the Poster

Mucha conducts the eye like an orchestra. A passerby first reads the top banner, then falls to the profile, slides along the curve of the nose to the necklace, loops through the chain of pendants to the hair, and is caught by the large circular halo with its marching ornaments. From there the gaze runs along the outer ring of letters spelling “Savonnerie de Bagnolet,” dips to the calendar blocks, and rises again in a cycle. This choreography ensures that the brand is read, the image savored, and the utility registered, all within a few seconds.

Lithographic Craft and Surface

Printed by F. Champenois, the poster shows how color lithography could deliver subtlety at scale. Flat tints are laid smoothly, gradients are achieved through careful crayon work on separate stones, and the black keyline holds forms together without crushing them. Look closely at the halo’s gray; it is not a single color but a gently modulated field that feels like carved surface. The metalwork’s highlights come from small reserves of paper left untouched, which gleam a little brighter than any ink. This economy of means is part of the poster’s luxe; it lets light seem to live in the sheet rather than on it.

The Dialogue between Medievalism and Modernity

The design borrows from medieval and Renaissance sources—profile portrait, jeweled crown, architectural halo—not to plunge into the past but to give modern soap a pedigree of craft. Mucha’s era loved to conflate new products with historicist imagery as a way of resolving anxieties about industrialization. Here, the effect is graceful. The machine that will make the soap remains invisible; what we see is the promise that industry can deliver hand-crafted refinement to the modern home. The poster is not nostalgic; it is aspirational.

The Feminine Ideal and Agency

Much of Mucha’s commercial work centers women, but the roles vary. In some posters, the figure is an enthroned muse; in others, a modern professional; here, she is a dignified emblem. Importantly, she does not perform for a viewer. Her gaze is lowered, her mouth relaxed, her bearing self-possessed. The message is not “buy this to become desirable” but “this product participates in your own regime of care.” That subtle shift gives the poster its respectful tone and helps explain why Mucha’s images still feel gracious rather than exploitative.

Brand Credibility and Claims

Along the right-hand border a vertical panel announces “Membre du Jury, Exposition Universelle, Paris 1889,” a clear claim to expertise and prestige for Alfred Schweizer, the name that appears on the top banner. Mucha incorporates this line as ornament, the letters aligned with the curve of hair so the credential reads as part of the composition rather than an intrusive footnote. In a single stroke the poster marries allure to authority, aesthetics to reassurance.

The Necklace as Microcosm

The beaded necklace at the base of the neck is a microcosm of the whole design. Small red cabochons alternate with green and blue elements; delicate fringe descends in cream and russet; tiny metal settings catch light. It is a miniature calendar of repeated motifs, organized and rhythmic. Within the poster’s logic, the necklace is skin’s reward for soap: after care, adornment; after ritual, celebration. The sequence is all implication and all the more effective for it.

Comparisons within Mucha’s Oeuvre

Placed beside Mucha’s “Nestlé’s Food for Infants,” created the same year, this poster shows the artist’s range. Both adopt the halo form and integrated type, but where the Nestlé design is domestic and tender, “Soap Factory of Bagnolet” is aristocratic and luminous. Both use product credibility differently: one places a tin in a kitchen scene; the other names a jury membership. The constancy across them is the belief that design should make life feel elevated, that utility need not be plain.

Why the Poster Still Works

More than a century later, the poster remains persuasive because it engages emotion without noise. The face is calm, the forms are legible, the palette is harmonious. The brand and its craft claims are readable at a glance, while the image rewards minutes of looking. Even the calendar panels—often discarded in modern reproductions—testify to an intelligent respect for the viewer’s world. The poster assumes a home, a year, and a rhythm of care. That assumption is flattering; it invites us into a world where design thinks about our time as well as our eyes.

Conclusion

“Soap Factory of Bagnolet” is one of Mucha’s most accomplished demonstrations of how advertising can behave like art without losing clarity. A crowned profile, a stone-like halo, and integrated lettering transform a toiletry into a heraldic emblem of cleanliness. Ornaments sparkle but never clutter; color warms without shouting; utility nests within beauty. The poster promises not simply that a soap will wash, but that it will participate in a cultivated life—a life whose calendar is measured by small rituals of care and whose rooms are brightened by good design. In the rush of the boulevard, such a promise would have felt both luxurious and attainable, which is why people kept these sheets long after the year printed at their bottoms had ended.