Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

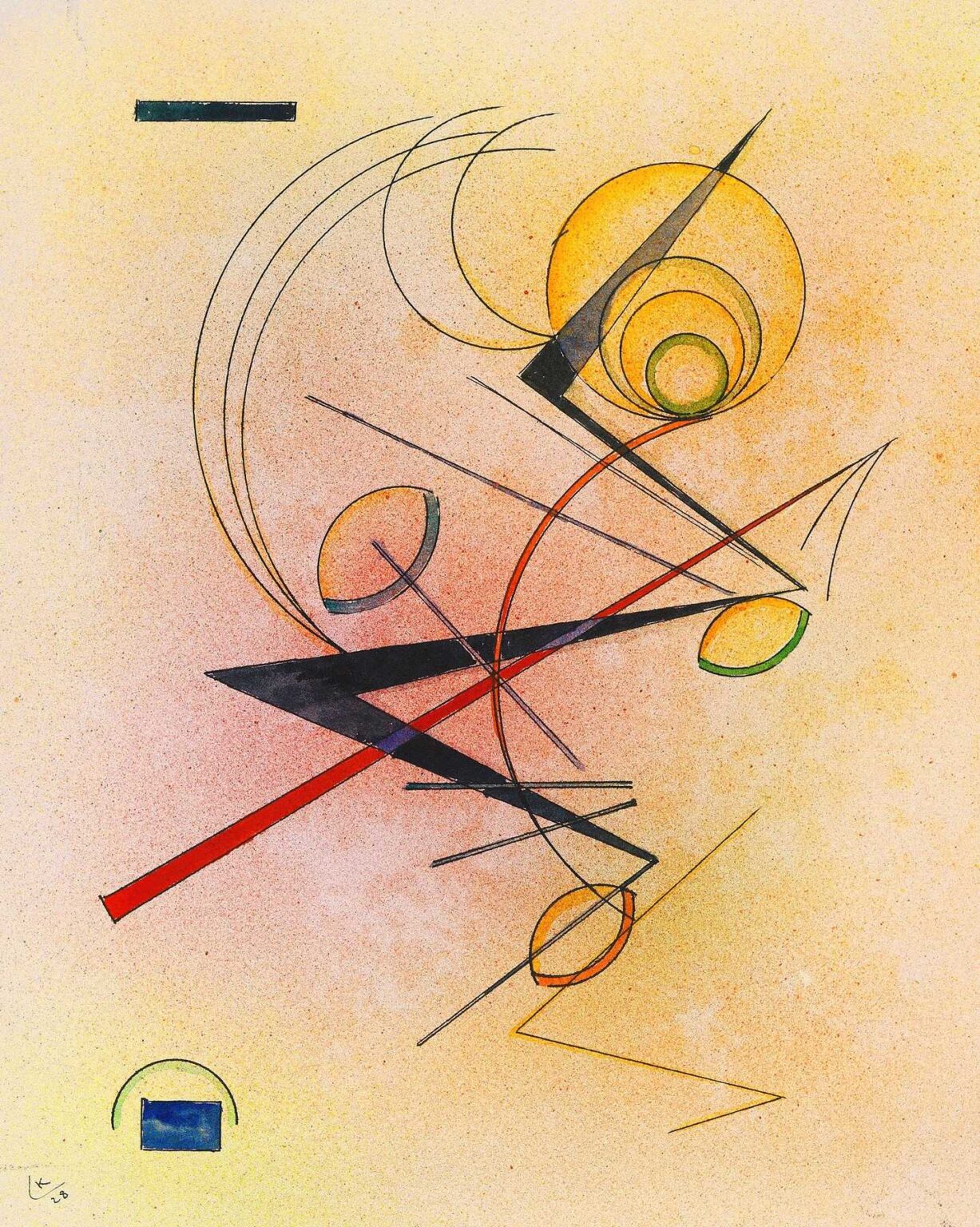

Wassily Kandinsky’s Small Warm (1928) manifests the artist’s mature vision of abstraction, where geometry, color, and line coalesce into an intimate, radiant composition. Executed as a lithograph during his late Bauhaus period, this print unfolds like a quiet symphony of warmth and motion. Rather than towering diagonals or sprawling color fields, Kandinsky here employs a more delicate touch: soft ochre textures suffuse the background, while slender black and red lines punctuate the space. Small ovoid shapes, rendered in muted greens and golden yellows, float in equilibrium. Despite its modest title, Small Warm exudes a profound sense of emotional resonance, inviting the viewer into a softly glowing microcosm of inner light and harmonious form.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1928, Kandinsky had spent several years teaching at the Bauhaus, where he embraced the interplay between art, architecture, and design. His earlier exuberant improvisations gave way to more disciplined explorations of form theory and color harmony. Lithography provided Kandinsky with a versatile medium—allowing for subtle tonal gradations, crisp line work, and layered overlays of color. Small Warm emerges at the nexus of his theoretical investigations and pedagogical commitments. The print reflects both the clarity of his constructivist leanings and the lyrical expressiveness that had defined his pre‑war abstractions. It stands as a testament to Kandinsky’s belief that even the smallest gestures of line and hue can convey vast emotional and spiritual depths.

Title and Thematic Resonance

The title Small Warm suggests an intimate spark of energy, a concentrated kernel of heat within a broader expanse. Kandinsky often used titles to guide the viewer’s emotional reception without prescribing literal narratives. Here, “warm” refers not solely to color temperature but to the print’s affective tone—a gentle invitation to feel comfort, vitality, and inner glow. The adjective “small” hints at the modest scale of forms and the subtlety of their interplay. Rather than overwhelming the viewer with grand spectacle, Small Warm cultivates a sense of introspection, as though one is drawn into a private chamber of quiet radiance.

Formal Composition

At first glance, Small Warm divides its space across a soft ochre wash that covers the sheet, providing a warm, unified field. Over this tone, Kandinsky arranges a series of sinuous black arcs that sweep across the composition from left to right, suggesting gentle currents of movement. A bold red line cuts through the center at a diagonal, intersecting with a thicker black diagonal that anchors the forms. Around these primary axes, small ovoid shapes appear—some filled with pale green, others outlined in yellow—each accompanied by slender linear tails or faint radiating arcs. Two compact geometric forms—a blue rectangle paired with a green half‑circle at the lower left, and a small off‑white square near the top right—provide counterpoints that balance the composition’s fluidity with moments of structural repose.

Color and Emotional Atmosphere

In Small Warm, color operates less as bold declaration and more as whispered resonance. The ochre background suffuses the entire print with ambient glow, akin to dusk light bending through a window. The red diagonal line, though thin, imparts a subtle surge of vitality, as if a heartbeat pulses across the surface. The green and yellow ovals, reminiscent of dawn buds or glowing embers, float with gentle buoyancy. These hues adhere to Kandinsky’s theories of color emotion: green for equilibrium and growth, yellow for spiritual intensity and illumination, red for life force. Together, these carefully calibrated tints weave an emotional tapestry that is simultaneously contemplative and quietly invigorating.

Dynamics of Line

Line in Small Warm dances between austerity and lyrical grace. The dominant black diagonal, broad and confident, provides structural gravitas, while the slender red line adds nimble counterpoint. The sinuous black arcs—five in succession—trace soft crescendos that lead the eye across the ochre field. Fine, almost imperceptible pencil‑thin lines extend from the primary forms, suggesting the faint after‑echoes of movement, like echoes in a softly hushed room. Kandinsky’s use of line here is akin to breath: the thick strokes represent exhalations of form, the thin strokes capture the delicate inhalations between gestures. This rhythmic interplay generates a sense of living energy that animates the print’s otherwise quiet surface.

Spatial Ambiguity and Depth

Without recourse to traditional perspective, Small Warm constructs a subtle sense of depth through layering and scale. The ochre wash recedes uniformly, but the overlapping diagonals and intersecting arcs create zones of perceived foreground and background. The larger black diagonal appears to hover above the red line, which in turn seems to cut across the arcs and ovals. The small rectangle and half‑circle at the lower left sit against the ochre with firm clarity, anchoring that corner in shallow relief, while the tiny square near the top right floats in a more ethereal register. This careful arrangement of scale and overlap invites prolonged viewing: each return to the print reveals new spatial relationships within its petite framework.

Technical Mastery of Lithography

Lithography offered Kandinsky a means of achieving both painterly textures and precise line. In Small Warm, the ochre ground likely derives from a spray or crayon application to the stone, producing a velvety tonal film. Over this, darker inks were drawn for the crisp diagonals and arcs, requiring steady draughtsmanship and exact register. The pale green and yellow ovals, as well as the red line, would have been printed successively, each on its own stone, demanding rigorous alignment to maintain the integrity of their intersections. The slight variations in ink density—visible in the ochre’s granularity and the red’s occasional feathering—lend the print an organic warmth that belies its geometric precision.

Symbolic and Spiritual Dimensions

Although devoid of representational imagery, Small Warm resonates with Kandinsky’s spiritual convictions. The diagonal lines can be seen as dynamic pathways of spiritual ascent, while the softly glowing ovals serve as luminous centers of inner awakening. The arcs suggest the cyclical nature of breath, thought, and cosmic rhythm. Kandinsky believed that pure form and color could awaken the viewer’s inner necessity—an urge toward spiritual realization. Here, the print functions as a meditative talisman: its modest scale encourages close, contemplative engagement, and its harmonized elements foster a sense of inner calm and hopeful transformation.

Emotional Engagement and Viewer Response

Engaging with Small Warm can evoke a soothing emotional resonance. The warm ochre invites feelings of comfort and safety; the buoyant ovals suggest gentle optimism; the intersecting lines convey subtle momentum rather than forceful drama. Because the composition avoids overwhelming spectacle, viewers are free to project personal memories and moods onto its forms—a glow reminiscent of candlelight, the hush of morning fog, or the soft rustle of wind through leaves. Kandinsky intended this open‑ended invitation: abstraction as a mirror for individual psychology and spirit, allowing each observer to complete the work through their own inner dialogue.

Relationship to Kandinsky’s Later Work

Small Warm occupies a distinctive place within Kandinsky’s late Bauhaus output. Compared to the crisp geometric abstractions he would produce in the 1930s—dominated by stark color blocks and precise shapes—this 1928 print reveals a lingering lyricism and textural subtlety. It bridges his earlier improvisational vigor with his later emphasis on structural clarity. The print’s delicate washes and sinuous arcs recall his formative experiments with watercolor, even as its economy of form anticipates the restraint of his final years. As such, Small Warm encapsulates the painter’s lifelong dialectic between freedom and discipline, emotion and order.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

Over ninety years since its creation, Small Warm continues to inspire contemporary artists and designers. Its soft palette and balanced geometry find echoes in modern minimalist interiors, graphic identities, and digital interfaces seeking a harmonious interplay of color and line. Art historians view the print as a vital example of Kandinsky’s late style, demonstrating how abstraction can convey nuance and intimacy as powerfully as grand compositions. In the broader narrative of 20th‑century art, Small Warm affirms that even the subtlest gestures—small forms, warm hues, slender lines—can resonate with emotional and spiritual depth, offering viewers a quiet sanctuary within the visual whirlwind of modern life.

Conclusion

In Small Warm (1928), Wassily Kandinsky distills his synesthetic theories, Bauhaus formal rigor, and enduring spiritual quest into a tender yet dynamic lithograph. Through its gentle ochre field, intersecting diagonals, floating ovals, and whispered lines, the print creates a compact universe of warmth, movement, and contemplative grace. Far from being a mere study in geometry, Small Warm embodies Kandinsky’s vision of abstraction as a vessel for inner illumination and emotional resonance. It stands as a testament to his belief that even the smallest artistic gestures can ignite profound inner light—an invitation to discover warmth within the delicate interplay of form and color.