Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

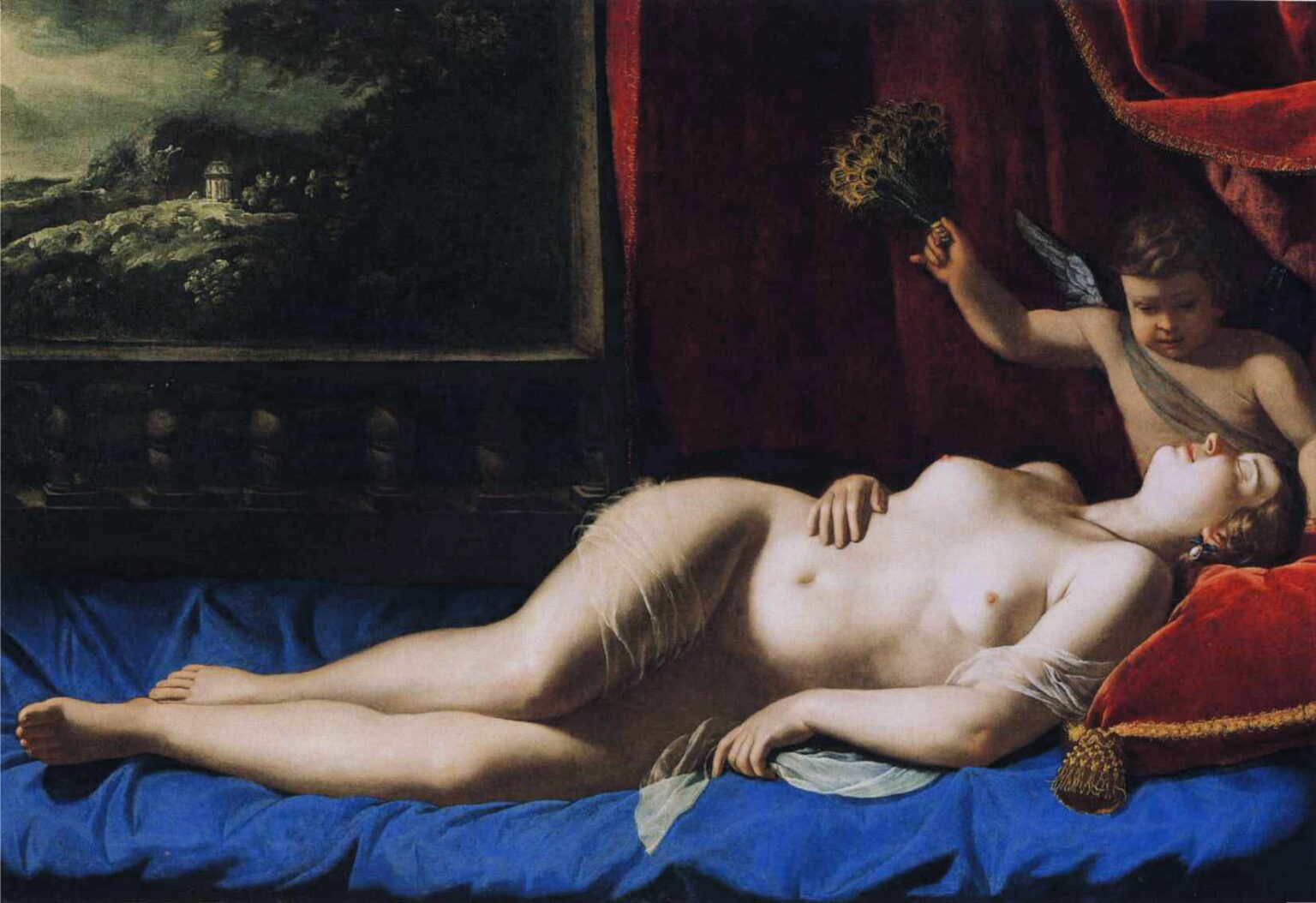

Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Sleeping Venus” (1630) transforms a well-worn mythological subject into a private drama of breath, warmth, and light. The goddess lies diagonally across a lapis-blue bedcover, her body surrendered to sleep while a small winged Cupid cools her with a fan of peacock feathers. A crimson curtain descends like a theater canopy, and at the far left a framed landscape opens onto a distant pavilion beneath a silvery sky. The composition is sensuous without clamor, ceremonial without spectacle. Rather than parade Venus as a public emblem of beauty, Gentileschi invites the viewer to witness a moment of vulnerability and repose, where touch, fabric, and air become the true actors.

Historical Context

By 1630, Gentileschi had established herself as one of the Baroque’s most accomplished narrators of embodied experience. After formative years in Rome and Florence and a period in Naples, she moved among courts that prized mythological subjects for their blend of erudition and display. The theme of the sleeping Venus had long prestige, from Giorgione and Titian to later Roman and Bolognese variants. Many treatments leaned toward courtly theater—outstretched goddesses framed by landscapes and attendants, their nudity a polished pretext for allegory. Gentileschi inherits the tradition yet recasts it through her characteristic realism, tenebrism, and psychological tact. The result is an image that satisfies the period’s appetite for classical elegance while insisting on the body’s credible weight and the quiet specificities of a private room.

Subject And Narrative Moment

The painting captures Venus not as triumphant love but as sleeping sensation. Cupid’s small presence confirms the mythic identity and introduces a gentle narrative: the god of love tends his mother, fanning her with peacock feathers associated with Juno’s watchfulness and with luxurious courts. The action is minimal yet telling. This is not a seduction, not a judgment, not a revel. It is an interval when the goddess’s power is at rest and her beauty is unguarded. The slumber registers in the parted lips, the softened hand near the hip, and the long, unselfconscious line of the legs. The scene therefore turns a public symbol into an intimate human state—sleep—making Venus less remote and more embodied.

Composition And The Architecture Of Repose

Gentileschi composes the picture as a conversation between two rectangles: the bed with its saturated blue and the framed landscape that opens the left side of the room. Venus’s body forms a steady diagonal from lower left to upper right, a classic Baroque device that introduces motion into stillness. The red pillows and curtain, with their gold tassels and trim, make a cradle of warmth around her head and shoulders, balancing the coolness of the blue coverlet. Cupid perches in the upper right like a counterweight, his arm lifted in a curve that echoes the goddess’s reclining contour. The whole arrangement is spare and legible, a stage set designed to keep the eye moving along the body’s rhythms without dispersing attention.

Light, Shadow, And The Tenebrist Veil

A concentrated light enters from the right, sliding across Venus’s torso and legs before sinking into cooler shadow at the far left. The modeling is frank and tactile: highlights gather along the breastbone, kneecap, and forearm; half-tones soften the lower abdomen and the turn of the hip. Shadow is not a void but an atmosphere that cools color and gives forms their privacy. The tenebrism is calibrated to an interior, domestic register—no blinding, theatrical beam, but a lamplike clarity that honors skin and fabric. This light makes the viewer conscious of temperature: warm where flesh meets the heated pillow, cooler across the stretch of thigh, cooled again by Cupid’s fan as air moves over the skin.

Color And Emotional Temperature

The chromatic design is a triad of blue, red, and flesh. The blue coverlet anchors the base with a saturated, almost mineral intensity, making the skin appear luminous by contrast. The crimson textiles, edged with gold fringe, supply ceremonial dignity and an undertone of heat. Flesh tones range from pearly highlights to faint rose and honey—never lacquered, never anonymous. Gentileschi’s palette avoids sugary pinks in favor of colors that suggest blood and breath in motion. Even the landscape at left is toned in subdued greens and grays, like a memory cooling at the edge of consciousness. The overall temperature therefore oscillates between warmth and repose, a chromatic analogue to the painting’s theme.

The Nude And The Ethics Of Realism

Gentileschi’s Venus is a body, not a marble. The stomach relaxes with sleep; the hand resting near the hip is heavy with inertia; the right foot flexes gently outward rather than aligning to an ideal curve. These observations are neither corrective nor polemical; they are the painter’s method for making myth human. The diaphanous veils that cross the hip and arm are true to their material—thin, catching tiny lights, doing almost nothing to conceal. The nudity is frank yet unprovocative, because the posture belongs to rest, not to display. The viewer’s gaze is acknowledged and managed by composition and light, but it is not solicited by the figure’s awareness. The ethics here align with Gentileschi’s broader project: to respect the subject’s interior state even when depicting a body beloved of allegory.

Drapery, Textiles, And The Theater Of Comfort

The painting is a study in textures. The velvet cushion under the head absorbs light in a soft bloom; the gold tassel gathers it in bright points. The blue bedcover ruckles in heavy folds, the paint thickening along crests where the light catches. The translucent veils leave faint, feathery edges where they skim the skin, suggesting the tickle of fabric over a resting wrist. The fan’s peacock feathers are massed rather than counted, their eyes implied by small, warm sparks that read immediately at a distance. The material world does more than decorate; it creates the conditions of sleep—soft, weighty, slightly cool—and it disciplines the gaze away from prurient inspection toward a sensuous knowledge of surfaces.

Cupid As Attendant And Narrative Counterpart

The putto is both charming and purposeful. He leans over the pillow, eyes trained on the task, small wing half-unfurled, arm poised to keep air moving. His presence humanizes Venus and reminds us that even a goddess enjoys care. At the same time, Cupid introduces a ripple of motion that keeps the picture from stasis: the lift of his arm, the slight tilt of his torso, the arc of feathers over Venus’s temple. He acts as a silent conductor of air, the unseen element that cools flesh and stirs fabric. In many mythological nudes, putti flutter as décor; here the child labors, gently, and the scene earns its credibility.

The Framed Landscape And The World Beyond

At the left, a dark balustrade and a framed landscape open the room toward a distant world. The view reveals rocks, trees, and a small temple or pavilion under an overcast sky. The space reads like a painting within the painting or a window veiled by shadow. Its cool tonality and miniature scale contrast with the warm immediacy of the foreground. Functionally, the landscape measures distance in two senses: geographic distance from the world’s bustle and emotional distance from waking. It is as if the day waits politely outside while sleep continues to hold sway inside.

Sensation, Breath, And The Science Of Sleep

Gentileschi’s attention to bodily cues lets the viewer imagine how the scene feels. The relaxed mouth and long throat suggest deep, even breathing. The slight lift of the chest implies the rhythm of that breath beneath the skin. Fingers lay softly near the hip, not clasped, free of muscular intent. The fan cools the temple where pulse beats close to the surface; the pillow presses the cheek into a gentle crescent. Through such particulars the painting becomes almost audible: the whisper of feathers, the hush of fabric, the faint exhale. The artist’s famed command of drama is here turned toward the drama of quiet physiology.

Dialogues With Earlier Venuses

The sleeping goddess had illustrious precedents. Giorgione’s reclining Venus introduced the long, horizontal body in a landscape; Titian’s Urbino transformed it into a domestic interior of marital power; later painters multiplied variants that veered between poetry and parade. Gentileschi’s version speaks to these but complicates them. She pushes the body closer to the viewer, tightens the stage with heavy drapery, and adds a working Cupid. The erotic charge is tempered by a credible sense of rest. Where many predecessors plotted desire through the figure’s awakening gaze, Gentileschi removes the gaze entirely, preserving a privacy that commands rather than cajoles respect.

Gender, Agency, And Artemisia’s Perspective

Because Gentileschi is celebrated for giving women agency in violent or decisive moments, it matters that she extends that respect to a nude asleep. Agency here is not action but control of terms. Venus lies on her own stage, with her own air, under the care of her son. The composition shields her from the street of the landscape and from the viewer’s ownership; we are witnesses, not participants. In a genre often prone to instrumentality—women as surfaces for male allegory—this painting proposes a different contract. The body is central, but the inner life is sovereign, and the painter’s fidelity to sleep maintains that sovereignty.

Technique And The Illusion Of Texture

Gentileschi’s brush moves across distinct registers. Flesh is constructed from thin, warm glazes tightened with cool half-tones to shape bone and tendon. Fabric takes broader, directional strokes—satiny on the blue coverlet, plush and absorbent on the red velvet. The gold tassel is shorthand brilliance: a few thick, bright touches that coalesce into fringe at viewing distance. The peacock fan is suggested by layered, feathery marks that emphasize mass and motion over feather-by-feather description. Edges breathe where air would soften them—the shadowed hip, the receding calf—and sharpen where the eye must anchor—the elbow, the crisp fold near the wrist. Such decisions keep the image vivid yet unlabored.

Space, Scale, And Viewer Relationship

The figure is near life-size and close to the picture plane. The blue bedcover occupies the bottom edge like a stage apron, inviting proximity while establishing a boundary. The diagonal of the body draws the viewer’s gaze from feet to face, a slow traverse punctuated by the warm island of the pillow and the small flare of Cupid’s feathers. The interior’s limits are clear—curtain, balustrade, framed view—preventing the gaze from wandering and reinforcing the intimacy. The painting’s rhetoric is confidence rather than invitation: the goddess is present, the room is hers, and the viewer may look so long as looking honors the terms on offer.

Patronage, Function, And Courtly Use

A refined mythological nude such as this would have served multiple functions in an elite collection. It advertised classical literacy and painterly sophistication; it graced a bedchamber or private gallery with an emblem of pleasurable rest; it complemented companion pieces of sleeping or waking deities. Gentileschi’s particular handling—dignified, tactile, and psychologically considerate—would appeal to patrons who wanted the prestige of the subject without the brashness of voyeurism. The picture’s measured luxury—the peacock fan, the velvet and gold, the distant pavilion—aligns with courtly culture while preserving a distinctive authorial voice.

Legacy And Modern Resonance

Modern viewers often praise Gentileschi for images of decisive female strength. “Sleeping Venus” broadens that legacy by asserting the dignity of rest, the beauty of unperformed body, and the ethics of looking without possession. The painting’s persuasiveness lies in its sensory truth: one can feel the coolness of the sheet, the weight of the cushion, the whisper of feathers. Its restraint reads as confidence, its silence as eloquence. In a tradition that frequently made Venus a pretext, Gentileschi makes her a person—even when she sleeps.

Conclusion

“Sleeping Venus” is a masterclass in how to turn a celebrated allegory into a believable human scene. Gentileschi organizes color and light around a diagonal body, binds the goddess to a world of convincing textures, and frames everything with a red curtain that dignifies rather than merely decorates. Cupid’s gentle labor, the landscape’s cool distance, and the slow bloom of light across skin collaborate to produce a mood of protected intimacy. Nothing shouts; everything breathes. The result is an image that honors classical beauty while remaining loyal to the body’s truthful weight and the private grace of sleep.