Image source: wikiart.org

A Study That Breathes: Nature, Notation, and Nerve

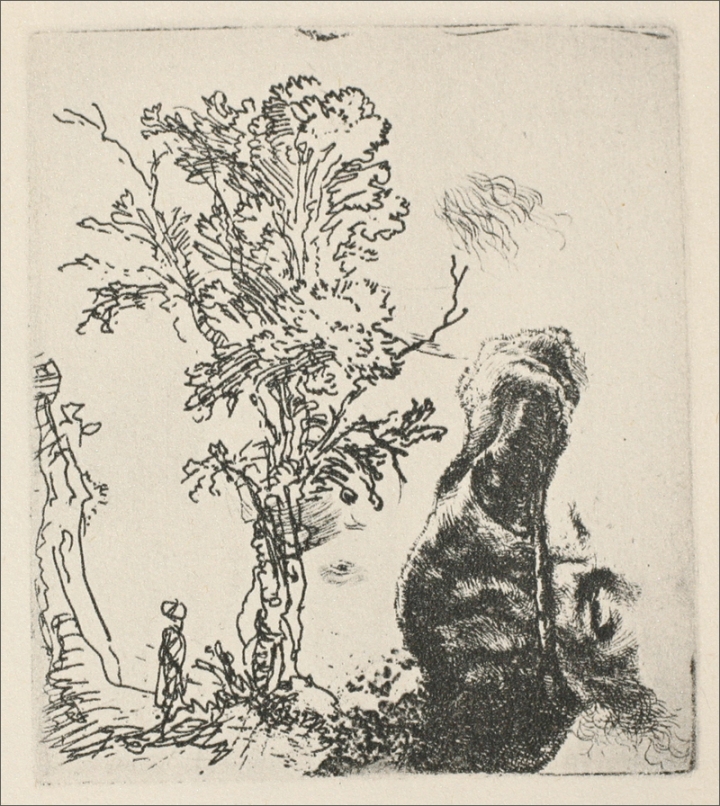

Rembrandt’s “Sketch of a Tree” (1638) is a small sheet with the amplitude of a landscape. In a handful of quick, elastic lines a sapling flares into life, a ground plane ripples, and an entire weather system seems to move through leaves and branches. At the right, a large head—printed on its side, boldly cropped—crowds the margin like a memory from another plate or a rehearsal in the same session. Between these two poles—living tree and thinking head—the image becomes a manifesto about looking: the world outside the studio and the world within a mind can be drawn with the same frank, searching line.

What, Exactly, Are We Looking At?

The left two-thirds of the sheet carry the titular tree: a lively trunk rising from a scuffed base, shoots and secondary stems twisting upward, foliage sketched as clusters of broken loops and flicks. Near the base a diminutive figure stands, hat and cloak indicated with two or three strokes, a measure that turns the tree into a tower. A second, leaner trunk appears at the far left margin like a neighbor or an earlier state of the same tree. The right third contains an oversized head seen in profile and printed sideways—nose, closed eye, beard—rendered with denser, fur-like hatching. The juxtaposition is startling and instructive. Rembrandt lets a landscape study share copper with a head study, revealing a workshop truth: drawing is thinking, no matter the subject.

Composition as Conversation Between Outer and Inner Worlds

The page reads like a dialogue. On the left, the line is airy, springy, almost calligraphic—an outdoor voice. On the right, the line compacts into cross-hatching and pelt-like textures—a studio murmur. The blank field between tree and head acts as breathing space and also as hinge; our eye toggles back and forth, comparing how a branch and an eyebrow receive the same energy at different scales. In an age that prized finished presentation pieces, Rembrandt shows process with disarming candor. The sheet’s compositional split is not an accident to be excused; it is the point: observation and imagination, nature and portrait, can occupy the same thinking surface without apology.

The Tree’s Grammar: Trunk, Thrust, and Flutter

Rembrandt builds the tree with a grammar of three strokes. First, a bold, slightly bowed trunk line establishes mass and lean. Second, quick, branching diagonals spring from the trunk like verbs modifying a subject. Third, small whorls and squiggles articulate foliage as rhythmic clusters rather than counted leaves. That choice matters. He refuses botanical pedantry and aims for the sensation of a tree—its sway, its restless edges, its habit of catching light and returning it in fragments. The result is not a portrait of one specimen but an argument about treeness: vitality over taxonomy.

The Little Figure and the Ethics of Scale

At the base of the larger trunk, a small figure stands almost ceremonially. Two strokes define a hat and crown, a soft wedge suggests a cloak, a single mark grounds the feet. The person gives the tree a human yardstick, but more importantly, the figure turns the study into a place. Without that measure, we have a motif; with it, we have a world. The humility of the figure—no face, no gesture—fits the sheet’s ethos: this is not a story scene; this is attention practiced in the open air.

Wind in the Lines

You can feel weather. The foliage marks are not symmetrical; they list slightly to the right, as if a breeze presses through the crown. A few stray hatchings in the upper field mimic detached cloud or the path of seeds. These are tiny decisions with big effect. Instead of a specimen in still air, the tree exists in time. The sketch becomes a recording of seconds rather than a diagram of parts. In Rembrandt’s best studies, motion is not drawn; it is implied by the way lines lean into one another.

The Head: Memory, Mass, and Maker

At the right, the large head—rotated ninety degrees clockwise within the print—changes the temperature of the page. It is modeled densely, the beard marked by overlapping, animal-like strokes, the eyelid defined with short, weighted curves, the nose a heavy peninsula of tone. It could be a self-study or a quick notation of a studio companion. Printed sideways, it refuses narrative. Instead, it reads like an index of hand pressure: where the needle bit deeper, ink prints darker; where strokes feather, the form dissolves into paper. Set against the tree’s airy structure, the head asserts a different kind of observation: looking from within, building volume out of touch and memory, not light alone.

Etching as Drawing with Time Built In

“Sketch of a Tree” is an etching, not a pen drawing. That means every line we see was scratched through a wax ground on copper and then bitten by acid before the plate was inked and printed. The medium adds a delay between gesture and result, yet the sheet reads as immediate as graphite. Rembrandt’s mastery lies here: he treats the copper like a sketchbook. The tree’s lines are laid with the speed of walking; the head’s are laid with the patience of modeling. The combination shows a virtuoso willing to leave rehearsals in the final score.

The Plate as Palimpsest

The simultaneous presence of tree, secondary trunk, figure, cloudlet, and sideways head suggests the copper plate served multiple sitting and standing studies. Perhaps the head was tested first; perhaps the tree was added later; perhaps both were present and Rembrandt enjoyed the dissonance. Either way, the printed impression preserves a palimpsest of intentions. In a period used to polished finish, he gives us the archaeology of thought. That archaeology is the sheet’s deepest charm.

Negative Space as Atmosphere

Notice how much of the paper remains untouched. The sky is an ocean of blank; the ground is indicated by a few skids of line; the zone between head and tree is a clear corridor. That restraint is active, not passive. The untouched paper behaves as light and air, ventilating the cluster of marks so that the tree can seem sunstruck and the head can seem to hover. Many drawings suffocate under too much information; this study breathes because it knows what to omit.

The Calligraphy of Bark and Leaf

Look closely at the trunk’s edges. Rather than detailing fissures, Rembrandt uses broken, jittering strokes that flirt with abstraction. Bark becomes script. The foliage, too, is calligraphic—a string of arabesques and commas that resolve into leaf mass when seen at arm’s length. This handwriting confers personality on the tree without turning it into caricature. The rhythm of marks is legible as feeling: quick admiration, small corrections, and a refusal to lie about what the eye cannot see in a glance.

A Landscape Tradition, Subverted

Seventeenth-century Dutch art teems with tidy copses and carefully staged riverbanks. Rembrandt participated in that tradition—the 1630s give us “The Stone Bridge,” “Landscape with the Good Samaritan,” and other brooding panoramas—but he also sabotaged the genre from the inside with sheets like this. He declines the composed vista and gives us the fragment that inspired it. The sketch is landscape’s DNA: a coil of energy ready to unspool into a painting, yet complete in its own right.

Light, Notation, and the Mind’s Weather

Because the sheet is monochrome, there is no pigment to create light; there is only paper reserved and ink deposited. Rembrandt places a few darker knots within foliage clusters and leaves much of the crown airy, letting the paper’s brightness act as sun. The result is a head that feels heavy with earth and a tree that feels filled with light—two forms of weather on one page: interior shadow and exterior glare. The opposition is not just visual; it is psychological. The sheet records how a morning’s walk and an afternoon’s thought can live side by side.

The Little Path and the Invitation to Walk

Scratches at the base of the tree suggest a trodden path that runs toward the figure, then away behind the trunk. It is barely there, but it completes the sense of a walk. The viewer’s eye can step onto that path, circle the trunk, and exit the sheet toward whatever lies beyond. Rembrandt knew how a single line can turn a sketch into an invitation. In a studio full of dramas and saints, he still wanted a place to walk.

Why the Disjunction Works

Purists might object to the intruding head: doesn’t it break the illusion? In practice, it sharpens it. By leaving the head, Rembrandt forces the viewer to attend to the quality of line rather than to subject alone. We discover that the same nervous, elastic stroke can conjure both a branch and a beard, both a leaf mass and a cheek. Once you see that, the tree grows more alive, not less. The disjunction becomes a lesson about drawing’s unity—one intelligence, many worlds.

Process Made Visible, Not Excused

It is tempting to call the sheet a “scrap,” a leftover. That language misses the value rembrandt puts on process. He often kept and printed plates that bore exploratory marks, proud of the way the copper recorded thought. “Sketch of a Tree” belongs to that honest practice. Rather than burying experiments, he publishes them to invite us into the workshop. The print becomes a small democracy of marks: every stroke votes toward presence.

A Modern Feeling Across Centuries

Part of the sheet’s appeal today is its modernity. The cropped head, the unapologetic white space, the evident speed of line—these anticipate twentieth-century sketch practices and even aspects of comics and storyboarding. It feels contemporary not because Rembrandt predicted us, but because he trusted immediacy more than polish when truth required it. The tree is truer for being quick; the mind is truer for being shown mid-thought.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin at the little figure and scan up the trunk; pause where a branch splits and notice how the lines separate, then reunite. Drift through the crown: read the foliage as individual marks, then let your eye soften until clusters become leaf-light. Slide to the blank corridor and rest—feel the oxygen. Now turn to the head: trace the bridge of the nose, the fold of the eyelid, the furred beard. Let your sight jump between beard and bark. Return to the small path at the base and allow your eye to exit the sheet toward an imagined horizon. Repeat. Each circuit will teach you more about how a line can be both fact and feeling.

What the Sheet Teaches About Seeing

Above all, “Sketch of a Tree” argues for fidelity to sensation. Trees in life do not present themselves as tidy hierarchies of trunk, bough, twig, leaf; they present as motion and edge and light snagging on mass. Faces, too, do not arrive as lists of features; they appear as densities, textures, and small planes catching or refusing light. By placing tree and head side by side, Rembrandt says: both are solved by the same ethic—look quickly, feel structure, and let the hand record without fuss.

Closing Reflection

This little etching is not a footnote to grander paintings; it is a manifesto in miniature. It trusts the viewer to find beauty in process, to accept a tree built from abbreviations, to honor a head that wanders in from another thought. If the page looks unfinished, that is because the world is always unfinished—breeze, beard, branch, and mind mid-turn. Rembrandt meets that world with a fearless line and leaves us a sheet that still feels warm from the hand.