Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

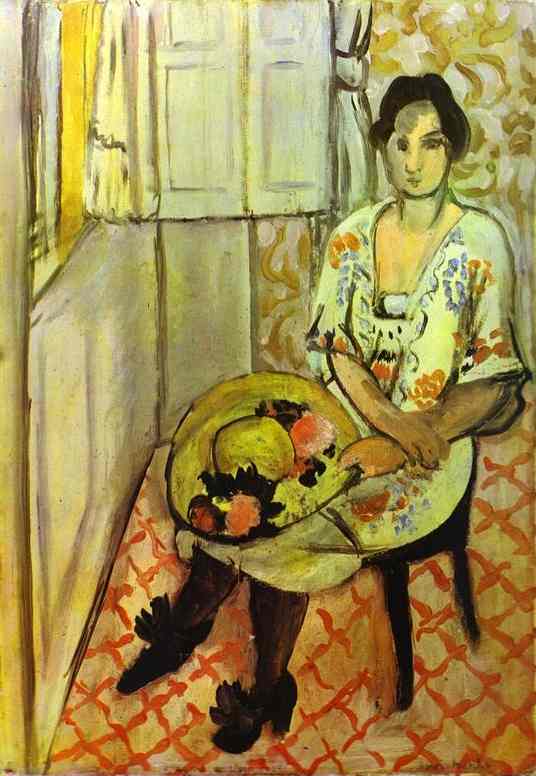

Henri Matisse’s “Sitting Woman” (1919) offers a luminous distillation of his Nice-period language, where pattern becomes structure, everyday objects become architecture, and a figure seated in a room becomes the axis of a carefully tuned world. A young woman in a floral dress sits at the right of the composition, hands folded and resting on a small round table. A broad straw hat trimmed with flowers lies in her lap like a portable still life. The red lattice of the floor pushes forward with rhythmic insistence, while a pale wall and shuttered window open a narrow triangle of gold light that slides down the left edge. Behind the sitter, a scroll of warm ochres and creams creates a decorative field that echoes the blooms on her dress. The painting breathes the tempered light of the Mediterranean and the postwar desire for order, clarity, and calm.

The Moment in Matisse’s Career

Painted in 1919, the picture belongs to the first years of Matisse’s so-called Nice period, when he relocated to the Riviera and reorganized his art around interiors, windows, and models posed in shallow space. After years in which he had demonstrated color’s capacity to shock and fracture, he chose an art of durable harmony. Decoration moved from embellishment to framework; pattern became the means by which space was clarified and pace was set. “Sitting Woman” shares its vocabulary with works like “Interior with a Violin Case,” “Woman with a Red Umbrella,” and the still lifes and nudes of the same year: a gridded or latticed floor to anchor the room, an open or shuttered window to turn exterior light into a luminous plane, and garments or textiles that carry modern ornamental rhythm without sacrificing human presence.

First Impressions and Motif

At first glance, the composition resolves into three registers. On the left, the wall and shuttered window are painted in chalky whites and soft grays; the narrow slit of yellow light at the far edge turns that modest corner into a quiet beacon. In the center, the red lattice floor tilts upward, its geometric network setting the tempo of the room. On the right, the woman occupies a dark chair. She wears a light dress sprinkled with floral notes in peach, blue, and violet, and a necklace that sets a dark accent at the collar. Her hat lies across the near edge of the small table, its brim crowded with flowers, as though she had just taken it off before sitting. Hands folded, head slightly angled, she looks outward with a calm that matches the painting’s measured order.

Composition and Framing

Matisse constructs the composition from diagonals and stabilized curves. The left wall and window form a long, receding wedge that leads the eye inward; the table’s circular top and the hat’s repeating ellipse answer with soft, stabilizing curves. The figure is placed to the right of center so that the rhythmic floor and the bright left edge can balance her mass. Cropping is intimate: the chair’s legs are cut; the shutter rises almost to the top edge; the floor pattern runs out of the frame. This closeness keeps the space shallow and the viewer near, a hallmark of the Nice interiors that allows the painted surface to remain emphatically present even as it hosts a believable room.

Color Architecture

Color carries the architecture more decisively than line. Three families of hues hold the composition. The first is warm and domestic: ochres and creams that weave through the wallpaper arabesques, the hat’s straw, and the flesh of the sitter’s hands and face. The second is cool and cleansing: the pale whites and grays of wall, curtain, and shutter, along with a skim of blue that sneaks into shadows and the dress’s floral marks. The third is the assertive red of the lattice, a coral-cadmium net that organizes the floor into a firm plane and strikes the high chord of the room. Because each family appears in more than one zone, the painting reads as a single chord rather than a set of isolated notes. The yellow slit of light at the left margin links all three families by touching the ochres in the wallpaper, intensifying the reds on the floor, and brightening the whites of the wall and curtain.

Light and Climate

The light is steady, maritime, and generous—the very climate that drew Matisse to Nice. There are few hard cast shadows; forms are turned by gentle shifts of temperature. Skin warms on the cheeks and fingers, cools in the crook of the arm; the dress remains airy because its white ground reflects the same light that washes the wall; the hat’s crown glows softly with pale lemon rather than dazzling. The left-hand window is a source not of view but of luminous paint; it acts like a slab of filtered daylight that reaffirms the room’s mild atmosphere. This evenly distributed light allows the lattice red and the floral motifs to sound without glare, keeping the mood hospitable.

Pattern as Structure

Pattern is the picture’s skeleton. The red lattice on the floor does what conventional perspective lines might have done in earlier centuries: it builds a plane and calibrates recession. It also gives the eye a measure against which everything else can be read—the angle of the table’s rim, the weight of the hat, the verticality of the sitter. Behind her, the wallpaper’s ochre curls perform a slower counter-rhythm, echoing the loops and dots in the dress while distinguishing wall from garment by scale and saturation. Pattern is never gratuitous. It is constructive, distributing energy across the surface and keeping shallow space legible.

The Figure and Costume

The sitter’s presence is poised rather than theatrical. Her posture is slightly formal—hands folded, legs together—but the softness of her dress and the casual position of the hat counter any stiffness. Matisse uses the garment to mediate between body and room. The floral sprigs on the fabric pick up colors from the wallpaper and the hat; the white ground provides a quiet interval amid the stronger red and yellow fields nearby. The neckline introduces a delicate rectangle of skin that rhymes with the window’s pale slab, and a necklace adds a dark punctuation at the throat. Her face, rendered with a few assured strokes, avoids portrait fuss yet conveys stability and attention.

The Hat as Portable Still Life

The hat lying on the table functions as a still life nested within the portrait. Its broad brim, pale citron crown, and cluster of dark flowers deliver a compact reprise of the painting’s principal colors. Placed at the edge of the small table, it creates a stepping stone between the figure and the viewer; the eye lands on the hat’s blossoms, slides along the brim to the sitter’s hands, and moves upward to her face. The hat’s circular form also modulates the geometry of the floor, softening the lattice’s angular insistence and tying the lower right quadrant into a readable whole.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Matisse’s line is frank and elastic. He outlines the figure with dark, confident strokes that thicken where weight gathers and thin where light diffuses. Around the hands and knees, the contour carries the tactile information the modeling deliberately avoids. The table’s round edge is brushed in a broad, slow arc; the hat’s ellipse is drawn with a hand that refuses mathematical precision in favor of living accuracy. In the wall and window, line relaxes so that color planes can meet without a fence, letting the light feel soft. This alternation between declared edge and open seam keeps the surface animated and the figure breathing.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The paint’s touch varies according to object and function. The lattice floor is laid in with firm, repeated strokes that allow the ground color to breathe through, producing a sense of fired tile without literal depiction. The wall and shutter are brushed more thinly, with quick, scumbled passes that permit the canvas to participate in the pallor of the light. The dress receives brisk, creamy touches for flowers and longer, diluted strokes for folds. The hat is painted more opaquely so its presence feels weighty; the petals decorating it are single, juicy dabs. Everywhere, Matisse lets the hand remain visible, the surest route to a painting that feels present-tense.

Space and Depth: Shallow but Habitable

Depth is achieved by overlap and scale rather than by traditional perspective. The small table overlaps the figure’s lap; the chair cuts behind her legs; the window wedge recedes, but only gently; the lattice shrinks as it moves upward, while its color cools slightly to suggest space. The result is neither flat diagram nor illusionistic room, but a designed field that a viewer can imaginatively inhabit. The closeness of everything to the surface is not a limitation; it is a strategy that keeps color relations crisp and the painting’s unity intact.

The Window and the Left Edge

The left edge of the canvas deserves attention. Matisse sets a narrow column of warm light along the extreme margin, as if a door had opened onto sun. That sliver brightens the adjacent wall and curtain and then slides diagonally down into the lattice, creating a luminous path that leads toward the sitter. The effect is subtle yet powerful: the light animates a zone of relative emptiness and prevents the right-heavy composition from feeling off balance. It also reinforces the Nice-period device of windows and doors as luminous planes rather than deep views.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The painting guides the eye by alternating strong beats and rests. Many viewers will begin at the hat, leap to the sitter’s folded hands, rise to the face, and then drift into the warm wallpaper behind her. From there the gaze slips left along the window’s pale wedge, falls to the spark of yellow at the far margin, and returns through the red lattice to the base of the chair. Each circuit reveals correspondences: the way the hat’s citron repeats the left edge light, how the floral marks on the dress echo but soften the wallpaper’s scrolls, how the black shoes punctuate the lattice’s rhythm without breaking it. The room becomes a score that the eye plays at a measured, humane tempo.

Psychological Tone

“Sitting Woman” is neither allegory nor anecdote. Its feeling is domestic, poised, and attentive. The sitter seems neither caught in reverie nor engaged in direct, confrontational gaze. She is simply present within a well-tuned climate of color and pattern. The painting’s deeper emotion resides in that tuning. After the upheaval of the preceding decade, Matisse’s Nice interiors propose a steadier pleasure: rooms where light is gentle, colors are proportioned, and pattern supports rather than overwhelms. The picture’s calm is not emptiness but an ethics of clarity.

Relations to Other Works of 1919

Compared with the bolder “Interior with a Violin Case,” this painting is more intimate and more focused on the exchange between figure and decorative setting. Compared with “Woman with a Red Umbrella,” which opens outward to sea and sky, “Sitting Woman” turns inward, making the window a quiet source rather than a view. Compared with the nudes on sofas from the same year, it is more clothed in pattern and less concerned with physical volume. Yet all share key strategies: a shallow stage, a large organizing plane underfoot, strong color intervals, and the visible, decisive hand.

Sources and Dialogue with Tradition

The floral wallpaper, the patterned dress, and the straw hat place the work within a long European conversation between portrait and domestic decor. Matisse admires and modernizes that lineage. Instead of the elaborate illusions of the nineteenth-century salon portrait, he offers a décor that acknowledges the flatness of the wall and the truth of the floor as a designed surface. His patterns recall textiles he studied in North Africa and in museum collections, translated into an idiom that is unmistakably his own. The hat with its flowers might suggest the fashionable accessories of Nice; in his hands it becomes a formal device that balances color and curve.

Likely Palette and Materials

The surface suggests a concise set of pigments handled with restraint: lead white across wall, shutter, dress ground, and highlights; yellow ochre and raw sienna providing wallpaper warmth and hat straw; cadmium red and vermilion striking the lattice; ultramarine and cobalt creating cools in the dress and faint shadows; viridian and chrome yellow mixing into floral accents; ivory black sharpening contours of chair, shoes, and hat trim. Paint is thin where air must circulate and thicker where mass matters. This economy allows color to carry structure without heaviness.

How to Look

The painting rewards both close and distant viewing. Stand near to see how a petal is a single touch and how the lattice’s red is broken enough to let the ground breathe, keeping the floor alive. Notice the slight adjustments in the outline of the hands and how a few darker strokes describe knuckles and tendons. Step back and feel the room resolve: the lattice becomes a calm grid; the wall’s ochres settle into a warm hum; the hat’s circle anchors the lower half while the window’s pale wedge balances the left. Repeat the loop; the relations grow more precise with each pass.

Lasting Significance

“Sitting Woman” crystallizes the Nice-period belief that modern painting can be generous without spectacle. It demonstrates how pattern can function as architecture, how a figure can be fully present without psychological drama, and how color can organize a room into a harmonious whole. The painting shows a way forward for twentieth-century art: a domestic scale that does not concede ambition, a decorative language that does not abandon rigor, and an attention to ordinary light that dignifies daily life. Its serenity is earned through design.