Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

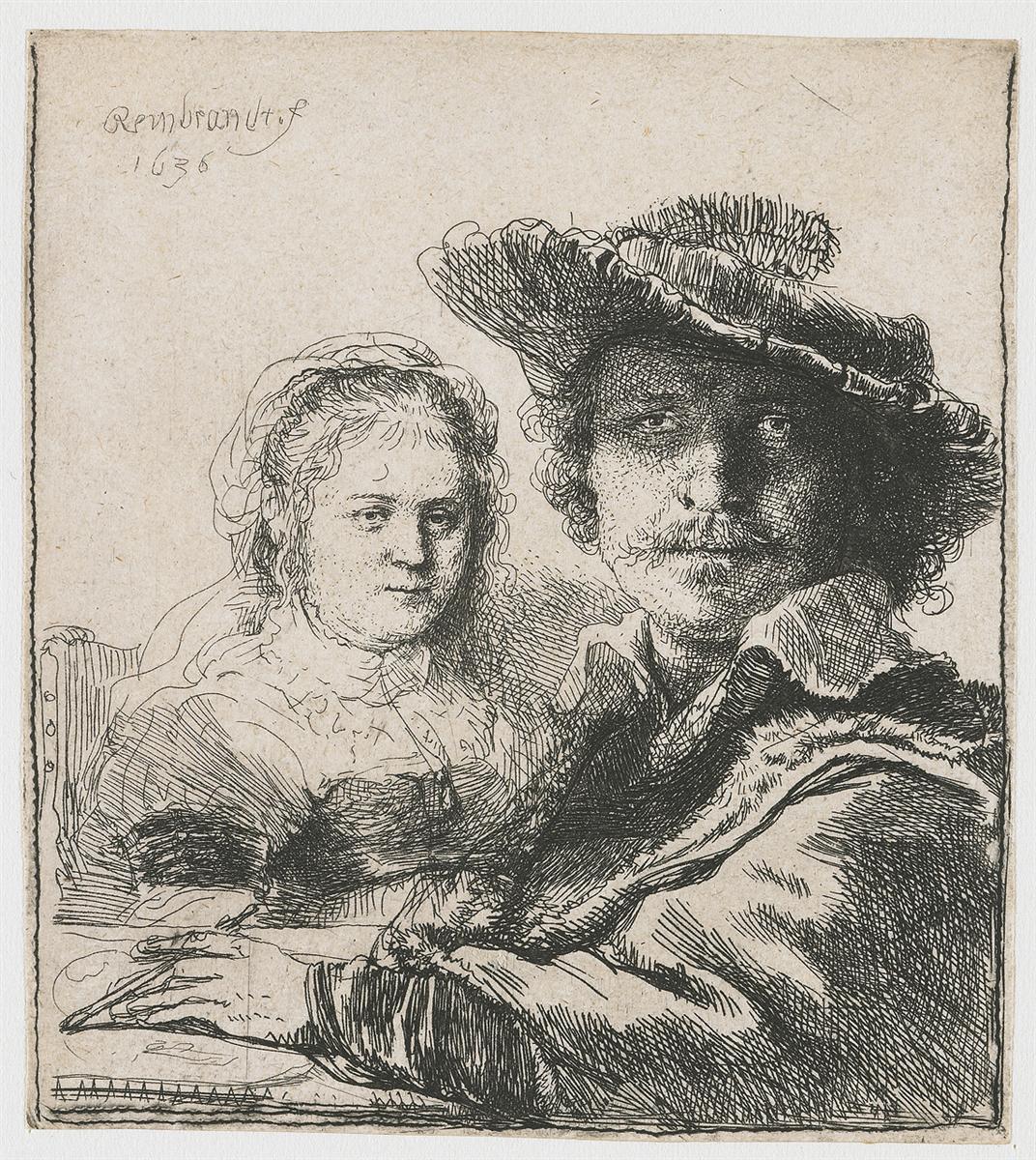

Rembrandt’s “Self-portrait with Saskia” (1636) is one of the most disarmingly intimate images of partnership produced in the Dutch Golden Age. Executed as an etching rather than an oil, the print presents two heads and a pair of interlocked hands pressed close to the picture plane: Rembrandt, brimmed hat casting a deep diagonal shadow over half his face, and Saskia van Uylenburgh, newly his wife, luminous and slightly behind him, as if stepping into the frame of his life. The sheet is modest in scale but expansive in feeling. It is not a studio demonstration or a commissioned likeness; it is a conversation caught in copper. Painter and muse become a married duo, not by allegory or costume but by the choreography of glance and touch. The result is a portrait of artistic identity braided with domestic tenderness, and a record of a young couple inventing a shared public image.

The Choice Of Etching And What It Means

Choosing etching for a conjugal portrait is itself meaningful. Prints were portable, intimate, reproducible, and comparatively affordable, well suited to circulate within a network of friends and collectors. For a newlywed couple whose social world included art dealers, poets, and civic patrons, a print could work as both keepsake and calling card. Rembrandt’s etching needle, roaming with improvisatory freedom, also suits the informal, conversational mood. The medium permits a quickness of thought—shifts in pressure, sudden hatching, feathery curls of hair—that would be slower to stage in oil. As a result, “Self-portrait with Saskia” feels like a drawing that decided to become a work of art in its own right.

Composition: A Duet At The Edge Of The Frame

The composition is radical in its proximity. Rembrandt crowds the figures up against the lower edge so that hands spill toward us and the hat’s brim nearly grazes the top. We are cast as table companions, not distant observers, and the intimacy is structural rather than sentimental. Rembrandt positions himself slightly forward, shoulders turned, hand resting on a tablet or book that doubles as a platform for the etched signature. Saskia appears just behind his left shoulder, her face smaller and more fully lit, her body modeled by quicker, airier lines. The overlap binds the couple into a single pictorial unit—a duet in counterpoint. He occupies the dark key, she the light; his features are broken by shadow, hers by soft hatching; his hat amplifies mass, her cap calibrates delicacy. This complementary design suggests not hierarchy but harmony: two roles that complete a chord.

The Drama Of Light And Shadow

Light in this print is not naturalistic; it is expressive. The brim of Rembrandt’s broad hat drops a diagonal bar of shadow across his face, covering the eye turned toward the viewer and throwing the other into half-glow. That shadow reads as privacy, as self-scrutiny, as the penumbra of thought before utterance—appropriate to an artist who often presented himself as watchful, skeptical, or amused by the spectacle of the world. By contrast, Saskia’s face is evenly lit, her features rendered with open strokes that suggest availability and warmth. Between the two heads ripples a gradation of mid-tone that fuses them visually: his darkness mellows into her light, her light warms his darkness. The marriage is therefore enacted through chiaroscuro as much as through likeness.

The Hands: Signature, Possession, And Partnership

At the bottom of the sheet Rembrandt’s hand rests upon a tablet whose edge runs parallel to the print’s lower border. It is both studio prop and symbolic platform. The fingers are quickly notated yet decisive, their placement claiming the surface as his domain. Just beside, Saskia’s forearms and hands are indicated with airy loops. No ring is ostentatiously displayed; the union is described through proximity and shared space rather than emblem. Rembrandt signs and dates the plate near the upper left, yet the true “signature” is the hand itself—the artist’s living tool—shown in the act of framing the world and welcoming Saskia into that frame.

Saskia As Presence Rather Than Accessory

In countless early modern portraits, a spouse serves as attribute, a decorative token of fertility or wealth. Rembrandt resists that reduction. Saskia’s head is drawn with independent authority: the slight tilt, the candid mouth, the eyes engaging the viewer directly rather than merely reflecting her husband’s fame. Even where lines are spare, the personality comes through. The bustling, fluttering strokes that sketch her bodice and sleeves grant her body a distinct energy. If Rembrandt occupies the role of brooding experimenter here, Saskia occupies the role of steady clarity. Their differing visual temperatures—his shadowed, hers luminous—create a balanced climate rather than a competitive forecast.

Costume, Social Identity, And The Theater Of Self

Rembrandt’s soft felt hat and fur-trimmed cloak are not casual wear. They belong to his repertory of studio costumes—hybrid garments that blend contemporary Dutch fashion with exotic trim. The choice announces artistic identity as a role one can inhabit and modulate. He is not a courtier playing aristocrat; he is an artist playing with the idea of artistic authority. Saskia’s modest cap and ruffled collar, meanwhile, anchor the scene in domestic Amsterdam. The combination signals a marriage of imaginative theater and civic respectability—a message likely reassuring to patrons contemplating commissions while also persuading collectors that Rembrandt’s studio was a place where invention and propriety could coexist.

Line As Conversation

Spend time with the sheet and a rhythm emerges. Rembrandt’s line thickens across his own cheek and curls, scratches into the felt of the hat, then lightens to a whisper around Saskia’s face. Short, nervous crosshatching knits form around his eye sockets; long, lyrical strokes float the contours of her cheek and cap. The difference reads like alternating voices in a dialogue: his dense and ruminative, hers clear and poised. Rembrandt thereby converts etching technique into character description without recourse to symbols or text.

The Psychology Of Proximity

There is a tender audacity in how close the heads are. These two do not merely cohabit the same composition; they share breath. That closeness makes the portrait feel less like an official presentation and more like a confession of dependence. Rembrandt faces us, but not alone; Saskia’s presence is woven into his public claim. It is as if he were saying, “This is who I am now—with her.” The statement carries unusual weight in a 1630s print culture thick with individual self-fashioning. Here is a young master refusing the myth of solitary genius.

Between Courtship And Commemoration

Dated 1636, the print belongs to the first years of the marriage. The freshness shows. There is none of the stately melancholy that shades Rembrandt’s late self-portraits; there is curiosity and play. One senses that the print may have grown out of a studio session in which the artist tested poses with a mirror and then invited his wife into the field of reflection. The result is halfway between an exercise and a keepsake, which is exactly its charm: it retains the warmth of the session—the light talk, the shifting chair, the pause to look—inside the finished object.

A Private Image Built For Public Circulation

Because it is a print, “Self-portrait with Saskia” could move through the same networks as Rembrandt’s biblical etchings and genre studies. Collectors could place it in albums alongside states of his “Christ before Pilate” or the famous beggar studies, building a portrait of the artist not only as image-maker but as husband and neighbor. The sheet’s informality made it feel like privileged access—a glimpse into the studio granted beyond the protocols of patronage. In this way, Rembrandt anticipates the modern artist who uses reproducible media to craft a public persona with genuine private notes.

Echoes And Foreshadowing In The Rembrandt-Saskia Story

Seen from the vantage of biography, the print acquires a poignant afterlife. Saskia would die in 1642, not long after the birth of their son Titus. Rembrandt’s later self-portraits carry the burden of that loss, often staging the artist alone under heavier shadows. In the 1636 sheet we see the early brightness of companionship, the sense that a face behind one’s shoulder could transform the way the world looks. That knowledge deepens the image without sentimentalizing it; the print remains fresh and unscripted even for viewers who know the later grief.

The Oval Of Attention And The Absence Of Setting

Rembrandt leaves the background largely unworked, a field of pale paper patterned only by a few directionless strokes. This postponement of context has two effects. First, it pushes the figures forward, increasing the immediacy. Second, it allows the viewer’s imagination to supply space: a table, a window, a sheet of copper awaiting the needle. The empty ground is like a pause in a sentence that lets the voice breathe. In removing furniture, Rembrandt makes attention itself the setting.

The Signature As Stage Direction

At the upper left Rembrandt inscribes “Rembrandt f. 1636,” the abbreviation for “fecit,” or “made this.” Placed high and left, the signature acts as a stage direction delivered before the action begins. It also acknowledges authorship in a double sense: he made the plate, and he made the version of himself we see. The placement avoids competing with the heads; the line of ink feels like a banner stating that what follows is a crafted presentation, honest but not naive about its own theatricality.

Comparisons With Other Couple Images

Rembrandt returned to the theme of the pair in drawings and paintings, from the raucous tavern scene “Self-Portrait with Saskia in the Parable of the Prodigal Son” to later domestic sketches. What sets this etching apart is its stillness and its equality. The prodigal painting is exuberant, worldly, and role-playing; the etching is quiet and face-forward, with both sitters meeting us as themselves. In the later pendant portraits of husbands and wives that Rembrandt painted for patrons, the partners face each other across space and status. Here, the couple shares a single visual breath. The etching feels less commissioned than chosen.

Humanist Friendship And The Republic Of Prints

The sheet belongs to a larger culture of image exchange within the Dutch Republic, where artists, writers, and merchants traded portraits and verses as tokens of esteem. “Self-portrait with Saskia” seems intended for that republic of friendship. Rather than proffering social rank, it offers human closeness; rather than celebrating wealth, it celebrates shared life at the table. That humanist spirit—an esteem for personality and mutual regard—was one of the currents that made Amsterdam’s art market so vibrant. Rembrandt turns it into line.

Technical Acumen: Hatching, Burr, And State

Technically, the print is a textbook of controlled improvisation. The hat’s underside is a dense knit of curved hatching, thickened in places to imply softness; the cheek and jaw are built with interlaced strokes that preserve micro-highlights of paper. Around Saskia, Rembrandt lets the needle skate, suggesting volume with a few directional strokes rather than a full weave. The differing densities calibrate focus: the dark burr under the brim pulls us into Rembrandt’s eye socket, while the open paper around Saskia’s brow and cheek gives her an airy immediacy. The plate’s state—crisp and unoverworked—matches the mood of the image, as if too much labor would betray the moment’s ease.

Emotional Intelligence Without Sentimental Props

No flowers, no clasped hearts, no overt marital symbols crowd the sheet. The emotion is in the way Saskia leans just enough to enter his space, in the way his body turns to make room, in the unforced parallel of their gazes. Even the difference in scale—the artist larger, the wife smaller—reads less as assertion than as a function of perspective: he is closer to the mirror, she a step behind. That calibrated restraint allows the feelings to surface on their own timetable as we look longer.

Reading The Print Today

For contemporary viewers living amid self-presentations carefully curated on screens, this 1636 etching feels startlingly modern. It offers a crafted persona—Rembrandt the maker—without severing that persona from the human relationships that sustain it. It acknowledges performance—the hat, the angle, the signature—while insisting that performance need not cancel sincerity. In this balance lies the print’s continuing power. It teaches how a public image can be anchored by private truth.

Conclusion

“Self-portrait with Saskia” is not just a likeness of two people in 1636. It is a theory of artistic life rendered as a duet. By pressing himself and his wife close to the viewer, Rembrandt proposes that creativity and companionship are interdependent; by staging the exchange in the reproducible medium of etching, he sends that proposal into the lives of many. The sheet demonstrates that intimacy can be public without becoming exhibitionist, that light and shadow can articulate character as persuasively as words, and that a marriage can be drawn with a handful of lines that never grow old. In a career dense with masterpieces, this small print remains among the most human.