Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

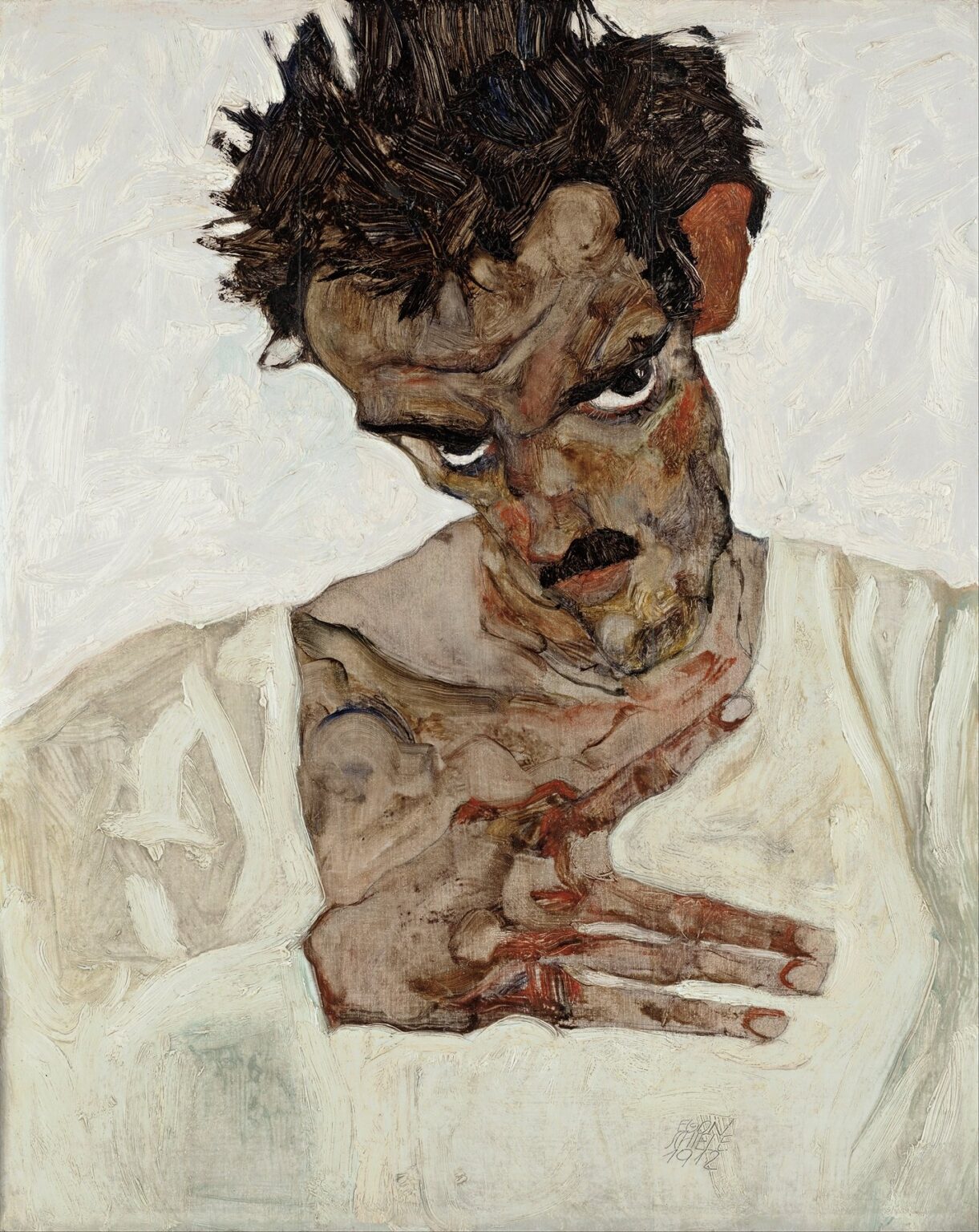

Egon Schiele’s Self-Portrait With Lowered Head (1912) stands as one of the most striking testaments to early Expressionism. At just 22 years old, Schiele had begun to forge a distinctive visual language defined by distorted anatomy, raw psychological intensity, and a fearless exploration of the human condition. In this work, the artist turns his gaze inward, presenting himself to the viewer not as an idealized portrait but as a fractured, biomorphic presence poised between vulnerability and defiance. The lowered head and penetrating eyes draw us into an intimate confrontation with the self, while the flattened pictorial space and aggressive line work announce a radical departure from academic traditions. This analysis explores the painting’s historical context, compositional strategies, formal innovations, and enduring emotional power.

Historical Context

Created in the summer of 1912, Self-Portrait With Lowered Head emerged during a period of frenzied experimentation in the Viennese art world. Gustav Klimt’s ornamental Jugendstil had dominated the previous decade, but younger artists—most notably Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka—were rejecting decorative surfaces in favor of an art that laid bare inner turmoil. Schiele studied briefly under Klimt yet quickly diverged, embracing a leaner palette and a focus on bodily tension. Politically, Austria-Hungary teetered on the brink of collapse, and the cultural landscape was rife with anxieties about identity, sexuality, and modernity. Schiele’s self-portrait responds to these uncertainties by interrogating the boundaries between self and other, observer and observed. The work also coincided with his participation in the Berlin Secession exhibitions, which exposed him to German Expressionists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, further intensifying his pursuit of psychological realism.

Visual Description

On a sheet of crinkled, off-white paper, Schiele has applied a combination of gouache and watercolor to render his own likeness. The composition is cropped tightly: the forehead, shoulders, and a single hand gesture occupy nearly the entire picture plane. The background is left almost bare, its rough texture hinting at preparatory pencil strokes beneath thin washes of pale pigment. Schiele has tilted his head forward and to the side, exposing the nape of his neck and casting deep shadows across his face. His eyes, heavy-lidded yet intense, peer out from beneath a fringe of tousled hair that seems to bristle with nervous energy. The hand, placed over the sternum, appears almost scabrous, the elongated fingers rendered in sanguine reds and murky browns. Minimal modeling conveys the skeletal structure beneath the skin, and areas of the hair and garment dissolve into a swirl of gestural brushwork.

Use of Line and Form

Line is the lifeblood of Schiele’s technique. Here, black contours oscillate between trembling precision and sudden, jagged outbursts. Rather than delineating smooth, classical surfaces, his strokes emphasize tension points—the jutting cheekbones, the angular collarbone, the knuckles pressing into flesh. This linear dynamism fractures the figure into planes and facets, producing a sense of structural instability. The contrast between thick, assertive lines around the hair and shoulders and thinner, threadlike lines around the eyes and mouth heightens the psychological drama. Schiele’s deliberate distortions—an overly broad forehead, an asymmetrical jaw, elongated fingers—are not caricatures but deliberate strategies to externalize inner states. The viewer’s eye is directed along these lines, compelled to follow the tension from the hand to the gaze, as if tracing the electric current of self-scrutiny.

Color and Texture

Schiele’s limited palette oscillates between ashen whites, muted ochres, dirty grays, and sanguine reds. He forgoes lush coloration in favor of hues that evoke pallor and desiccation. The face is infused with subtle reds around the cheeks and neck, suggesting both embarrassment and a faint vitality beneath the tremulous skin. The hand, by contrast, pulses with rusty crimsons that bleed into the chest, as if veins have surfaced and oozed pigment. The surface is textured unevenly: thick impasto in the hair region, scant washes in the clothing and background. This interplay of dense and transparent areas creates a palpable tension between materiality and void. In the shoulder and garment, broad strokes of white gouache flatten the form, emphasizing the figure’s emergence from an indeterminate space. Ultimately, the color choices reinforce the sense of exposure—this is not an idealized self, but a specimen under intense scrutiny.

Psychological Expression

More than a mere likeness, the Self-Portrait With Lowered Head delves into the fractured psyche of a young artist confronting his own anxieties. The lowered head suggests shame or depression, while the direct, almost accusatory gaze implicates the viewer in an unspoken dialogue. The hand pressed to the chest can be read as a gesture of self-protection or as a ritualistic invocation of the heart. By exposing his vulnerability so explicitly, Schiele transforms the portrait into a confessional act. The tension between retreat (the bowed head) and aggression (the fierce eyes) captures the ambivalence of youth on the threshold of adulthood. In this way, the work resonates beyond its biographical moment, touching on universal themes of self-consciousness, alienation, and the desire to be understood.

Context Within Expressionism

Schiele’s Self-Portrait With Lowered Head finds resonance with broader currents of Expressionism in Germany and Austria. Like The Bridge artists in Dresden and those of Die Blaue Reiter in Munich, Schiele sought to convey the subjective experience rather than objective reality. Yet his approach is uniquely intimate: he does not erupt into chromatic explosions but channels tension through line, form, and minimal color. Compared to Kirchner’s urban street scenes or Kandinsky’s abstract compositions, Schiele’s work zeroes in on the individual psyche. At the same time, parallels can be drawn with Otto Dix’s later self-examinations and Max Beckmann’s portraits of existential angst. In the context of Austrian art, Schiele stands out for his willingness to push the boundaries of figuration to their breaking point, foreshadowing themes that would dominate 20th-century art.

Technical Innovation

Technically, Schiele’s mastery lies in his synthesis of draftsmanship and painterly experimentation. He begins with a precise pencil underdrawing that charts the figure’s contours and anatomical landmarks. The application of gouache and watercolor over this drawing is both economical and bold: he often leaves areas unpainted, allowing the paper’s tone to contribute to the overall effect. In the hair and garment, he builds up layers of opaque white gouache, creating a sculptural relief against the smooth paper. His brushwork ranges from delicate feathering around the eyes to brutal scrapes of pigment on the hand. This interplay of additive and subtractive techniques gives the work a dynamic, tactile quality. Schiele’s willingness to leave traces of his process—the visible pencil lines, the uneven washes, the abrupt shifts in opacity—speaks to a modern sensibility that celebrates process alongside finished form.

Influence and Reception

In the years following its creation, Self-Portrait With Lowered Head became emblematic of Schiele’s uncompromising vision. While early critics found his distortions shocking and even obscene, later art historians recognized the radical sincerity at the core of his work. The portrait influenced subsequent generations of artists interested in psychological portraiture, from George Grosz’s satirical studies to Francis Bacon’s gut-wrenching canvases. In Vienna, Schiele’s brief but intense career helped to cement the city as a crucible of avant-garde art, bridging the decorative finesse of the Secession with the darker undercurrents of modernism. Today, the painting is celebrated for its pioneering exploration of selfhood, its raw immediacy, and its contribution to the evolution of 20th-century portraiture.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

More than a century after its execution, Self-Portrait With Lowered Head continues to speak to contemporary audiences grappling with questions of identity, mental health, and authenticity. Its direct engagement with inner turmoil anticipates today’s conversations around self-representation, social media personas, and the performative aspects of the self. Schiele’s unflinching portrayal of vulnerability resonates in an age where curated images dominate public spaces. Exhibitions of his work draw large crowds, and the painting frequently appears in retrospectives on Expressionism and psychological art. Its enduring power lies in its ability to collapse the distance between artist and viewer, inviting us to confront our own fragmented selves with honesty and compassion.

Conclusion

Egon Schiele’s Self-Portrait With Lowered Head remains a milestone in the history of modern art—a fearless exploration of the self rendered through masterful draftsmanship, evocative color, and uncompromising psychological insight. By stripping away decorative veneers and exposing the raw movements of line and emotion, Schiele crafted a portrait that transcends its biographical origins to become a universal meditation on human vulnerability. In confronting the viewer with his own unidealized image, he challenges us to acknowledge our inner fractures and to find beauty in the tension between concealment and revelation.