Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: Reclaiming the Canvas with Confidence and Color

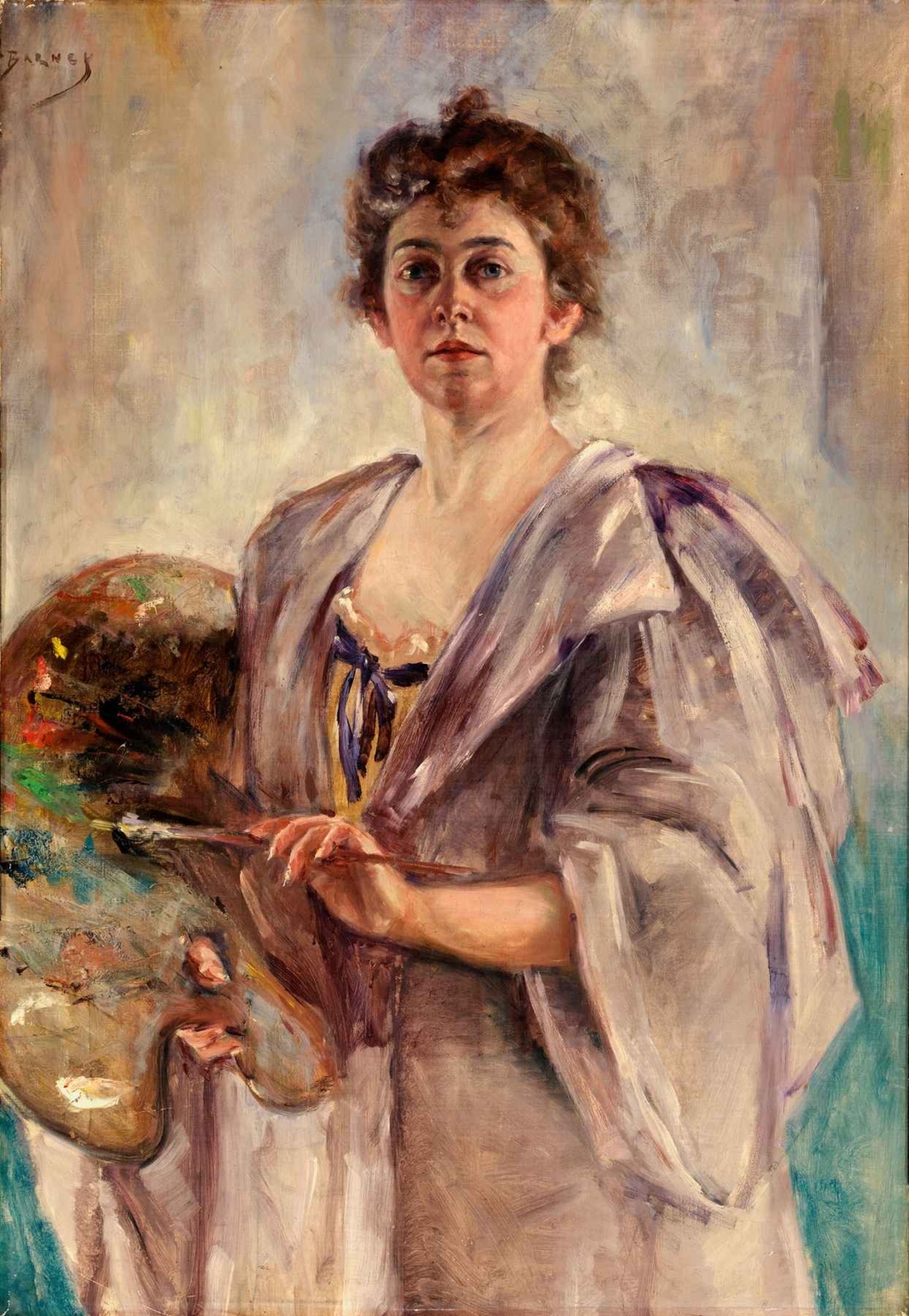

In Self-Portrait in Painting Robe, Alice Pike Barney does more than simply capture her own likeness—she asserts her identity as an artist, a woman, and a creator in her own right. Painted in the early 20th century, this vibrant and assertive self-portrait is a powerful declaration of creative autonomy. In an era when women artists still struggled for recognition and legitimacy, Barney’s confident gaze and brush in hand form a compelling visual manifesto.

This analysis explores the painting’s historical context, compositional elements, color theory, symbolism, gender dynamics, and legacy. We will uncover how Barney—a trailblazing artist, salonnière, and patron—used her own image to challenge gender roles and affirm her place in American and European art history.

Artist Background: Alice Pike Barney and the Art of Self-Invention

Alice Pike Barney (1857–1931) was a multifaceted figure—an artist, philanthropist, feminist, and cultural visionary. Born into wealth in Cincinnati, she trained under James McNeill Whistler in Paris and later immersed herself in the artistic circles of Washington, D.C., and Europe. Despite the societal constraints on women of her era, Barney forged a successful career in painting, supporting other artists and founding spaces for artistic dialogue.

Her oeuvre includes portraits, symbolist works, and numerous self-portraits, each revealing aspects of her complex identity. Self-Portrait in Painting Robe stands out for its directness and theatricality. With palette in hand and paintbrush poised, Barney does not merely depict herself at work—she stages her creative persona in a way that merges performance, authorship, and aesthetic command.

Composition: Poise, Power, and Painterly Confidence

The composition of Self-Portrait in Painting Robe is structured with clarity and confidence. Barney is depicted from the waist up, centrally positioned in a vertical canvas. Her torso faces forward, but her head turns ever so slightly, fixing the viewer with a composed, knowing gaze. The eye contact is direct and assertive—she is not the object of the viewer’s gaze but its master.

In her left hand she cradles a well-used palette daubed with rich colors, while her right hand, slightly forward, holds a brush mid-stroke. These painter’s tools dominate the lower half of the canvas, linking creative process with bodily presence. The painting is framed to accentuate her upper body, emphasizing the shoulders, head, and hands—key instruments of intellectual and artistic labor.

This balance between bodily realism and symbolic staging is part of the work’s enduring power. It communicates not just “a woman painting,” but “a woman as painter”—a subtle but important distinction.

The Robe as Costume: Performance and Artistic Identity

One of the most striking elements of the painting is the titular “painting robe”—a flowing, loose garment in silvery mauves and violets with generous sleeves. It resembles a theatrical costume as much as a utilitarian smock, aligning Barney with a lineage of romantic, bohemian creators rather than the buttoned-up conventions of salon portraiture.

The robe signifies more than comfort or style—it becomes a visual shorthand for Barney’s dual identity as artist and performer. It blurs the line between everyday labor and imaginative ritual, positioning her not just as a technician of paint, but as a conjurer of meaning.

The lush folds and reflective fabric also demonstrate Barney’s painterly skill. With swift but controlled brushwork, she captures texture, weight, and movement, transforming cloth into a medium for self-expression.

Palette and Color: Warm Flesh, Cool Robes, and Expressive Ground

Barney’s color choices in this work reflect a mature command of harmony and contrast. Her skin is rendered with warmth—peaches, roses, and amber tones create a lively, luminous surface. In contrast, the robe is painted in cool, silvery purples and muted blues, helping the warmth of her face and hands stand out.

The background is a diffused haze of neutral tones—beiges, pale lavenders, and hints of green—softly brushed to avoid distraction. This neutrality functions like a stage scrim: it isolates the figure while providing ambient context. The overall color scheme is feminine but unsentimental, elegant without being decorative.

The color palette echoes Whistler’s aestheticism—his preference for tonal unity and musical analogies—but with a more personal, tactile energy. It reflects Barney’s confidence in using color not just for form, but for mood and identity.

The Gaze: Confrontation, Self-Awareness, and Reclamation

Perhaps the most psychologically potent element of the painting is the gaze. Barney looks directly at the viewer, not with shyness or diffidence, but with full awareness of her own self-creation. Her expression is calm, poised, and slightly inquisitive—as if appraising the viewer as much as being appraised.

This confrontational gaze distinguishes Self-Portrait in Painting Robe from many historical self-portraits of women, where the subject often looks away or is distracted. Here, Barney controls the narrative. She is not “caught in the act” but fully staged in a moment of authorship.

Her eye contact asserts equality, making the viewer complicit in the act of artistic self-invention. In this way, the painting functions as both image and mirror: it reflects not just the artist’s likeness but her agency.

Gender and the Artist’s Image: Challenging the Male Gaze

In early 20th-century art, female self-portraiture was rare—and rarer still were depictions that foregrounded professional identity. Women were more often subjects than artists, muses rather than makers. Barney’s self-portrait subverts this pattern.

By showing herself at work, with palette and brush, she claims the artistic tools long monopolized by men. Her attire, while feminine, is functional. Her expression resists passive beauty or romantic affectation. She is not offering herself as a visual pleasure but presenting herself as a force of visual creation.

Barney’s work joins a lineage of assertive self-portraiture by women artists—from Artemisia Gentileschi to Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun to Suzanne Valadon—but it carries a modern edge. It reflects early feminist consciousness without overt didacticism, offering empowerment through aesthetic presence.

Stylistic Influences: Impressionism, Aestheticism, and Whistlerian Touches

Barney’s painterly technique reflects her training under James McNeill Whistler and her exposure to French and American impressionist circles. Her brushwork is expressive but controlled, particularly in the background and robe, where layers of color are blended and feathered for atmospheric effect.

Yet her face and hands are rendered with greater specificity, demonstrating classical technique adapted for modern purposes. The juxtaposition of loose and tight handling exemplifies a transitional moment in early 20th-century painting, where realism gave way to mood and gesture.

Whistler’s influence is also seen in the emphasis on tone, harmony, and the use of clothing and backdrop as abstract elements. But where Whistler’s female subjects were often distant and idealized, Barney’s is immediate and grounded.

Feminist and Cultural Interpretation: Art as Self-Assertion

Self-Portrait in Painting Robe can be read as a visual statement of autonomy, authorship, and artistic legitimacy. Created during a time when women were actively fighting for voting rights, access to education, and professional parity, the painting speaks to a broader cultural push for recognition.

Barney herself was an active supporter of women’s suffrage and artistic freedom. She used her social position to host salons in Washington, D.C., where artists, writers, musicians, and activists gathered. Her portraits of women often emphasized dignity and complexity rather than ornamental charm.

This self-portrait participates in that same cultural mission. It offers an image of the woman artist as whole, serious, and self-defined—neither muse nor mirror, but maker.

Legacy and Influence: A Forgotten Pioneer Revisited

Though Alice Pike Barney was a prominent figure in her time, her reputation faded in the mid-20th century. Today, efforts to recover women’s contributions to art history have renewed interest in her work. The Smithsonian Institution holds a large portion of her archive and artwork, recognizing her importance as both an artist and cultural patron.

Self-Portrait in Painting Robe stands as one of her most important visual statements. It has become emblematic of early feminist art and is increasingly included in exhibitions and scholarship focused on gender, modernism, and portraiture.

Its influence can be felt in later artists who used self-portraiture as a means of claiming identity—from Frida Kahlo to Alice Neel to contemporary artists working in performance and body art.

Conclusion: A Portrait of Power and Possibility

Self-Portrait in Painting Robe by Alice Pike Barney is far more than a depiction of an artist at work—it is a deliberate performance of authorship, dignity, and gender-conscious creativity. Through color, gaze, and posture, Barney reclaims the artistic persona as female, intellectual, and autonomous.

The painting bridges impressionist technique and feminist content, aesthetic pleasure and political presence. It invites the viewer not only to observe but to engage—to recognize the labor, intention, and identity behind the brush.

In doing so, it becomes not just a self-portrait, but a portrait of possibility: a vision of what women artists could be, and what their art could claim.