Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

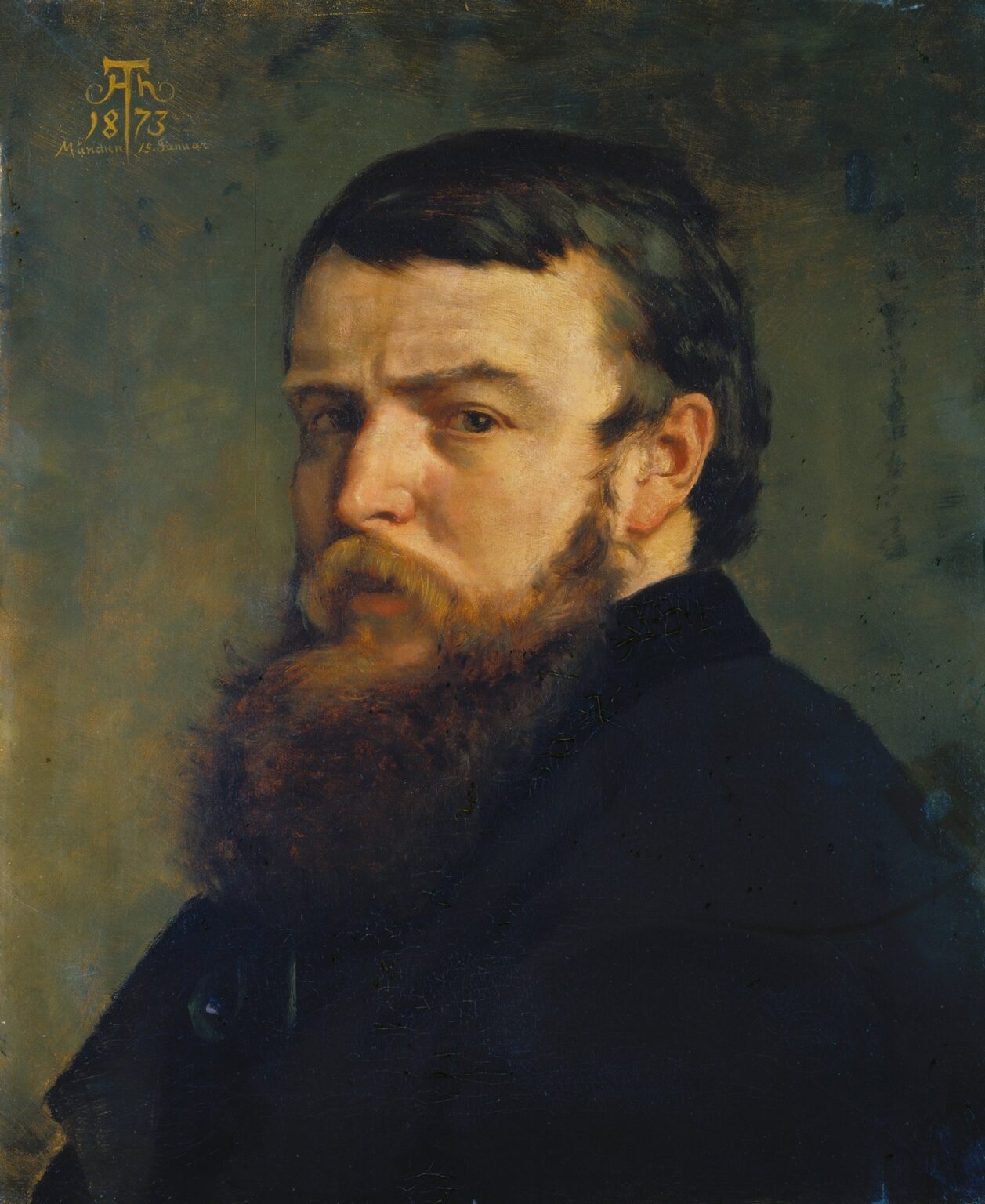

Hans Thoma’s Self-Portrait from Munich (1873) is a striking testament to the artist’s emerging mastery of portraiture and his evolving personal identity. Painted in oil on canvas, the work depicts the young Thoma gazing directly at the viewer, his features sharply modeled against a muted, nearly monochromatic backdrop. The intense stare, the luxuriant beard, and the carefully rendered textures of his coat speak to both technical prowess and psychological depth. This self-portrait marks a pivotal moment in Thoma’s early career: a confident assertion of his artistic presence in Munich’s vibrant cultural milieu and a declaration of his commitment to honoring both tradition and innovation.

Historical and Cultural Context

In 1873, Munich was a flourishing center of art and scholarship. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts, established in the late 18th century, attracted students from across Europe. Thoma arrived in Munich in the late 1860s, eager to immerse himself in academic training under established masters. Yet the city also buzzed with ferment: movements such as the Munich Secession would soon challenge academic orthodoxy, advocating for artistic freedom and the exploration of novel themes and techniques. Against this backdrop, Thoma’s self-portrait stands as a bridge between the rigorous academic tradition he was trained in and the more personal, introspective approach he would later embrace. The year 1873 also witnessed economic upheaval in Germany with the Gründerkrach financial collapse, an event that reverberated through cultural circles and may have influenced artists to seek solace in introspection and personal expression.

Artist Background and Influences

Born in 1839 in the Black Forest town of Bernau im Schwarzwald, Hans Thoma displayed early talent for drawing. He studied under the Nazarene painter Philip Veit at the Düsseldorf Academy, absorbing the Nazarenes’ reverence for early Renaissance purity and spiritual focus. Thoma’s subsequent travels to Italy exposed him to the coloristic brilliance of Venetian masters—Titian’s rich glazes and Giorgione’s atmospheric lyricism—while his time in the Netherlands deepened his appreciation for Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro and the intimate realism of Dutch genre painting. By 1873, Thoma had synthesized these influences into a unique style characterized by clear, sculptural forms, resonant color harmonies, and a deep engagement with both landscape and figural subjects. His Munich self-portrait offers a window into this moment of synthesis and transformation.

Compositional Structure

Thoma arranges the self-portrait in a tightly focused half-length format, his head and shoulders filling most of the canvas. The composition follows a classical schema: the sitter is centered, his eyes level with the viewer’s, creating an immediate psychological bond. Negative space, rendered in broad, muted strokes of greenish-gray, isolates the figure and prevents any extraneous elements from distracting the viewer. This simplicity of setting echoes the self-containment of the subject’s gaze. A subtle diagonal emerges from the slope of Thoma’s shoulders through the angle of his coat collar, lending a quiet dynamism to an otherwise static pose. The balanced composition underscores the gravity of the artist’s self-examination and the precision of his draftsmanship.

Color Palette and Tonal Harmony

Thoma’s palette in this self-portrait is surprisingly restrained, dominated by earthy browns, olive greens, and subdued ochres. His coat—painted in deep umber tones—absorbs much of the ambient light, while the flesh of his face and hands emerges in warm, pinkish ochres. The background’s olive-gray hue envelops the sitter, creating a tonal continuity that directs attention to the illuminated features. Highlights on the forehead, nose bridge, and cheekbones are rendered with a nearly pure white mixed with a hint of yellow, producing a soft but striking luminosity. The dark hair and beard, meticulously detailed with fine strokes of mixed brown and black, contrast sharply with the lighter skin tones, enhancing the facial modeling. This carefully calibrated color scheme reflects Thoma’s mastery of tonal relationships and his ability to evoke mood through subtle modulation.

Light, Shadow, and Modeling

The self-portrait demonstrates Thoma’s nuanced handling of light and shadow. A single, diffuse light source—likely imagined from the upper left—casts gentle highlights across the face and collarbone. Thoma employs chiaroscuro sparingly, favoring gradations of tone over stark contrasts. Shadows under the brow ridge, in the hollows of the cheeks, and beneath the lower lip are built with layers of translucent umber glazes, lending depth without heaviness. The beard, a central feature, reveals Thoma’s meticulous brushwork: individual strands catch the light with small touches of warm mid-tones, while the deeper recesses are shaded with cool indigo and burnt sienna. This interplay of light and shadow creates a palpable sense of three-dimensional form and a heightened presence that draws the viewer into the sitter’s intense scrutiny.

Psychological Presence and Expression

What makes Thoma’s self-portrait so compelling is the psychological immediacy of the gaze. His eyes, set beneath dark, slightly furrowed brows, hold a mixture of resolve, introspection, and perhaps doubt. The left eye, marginally shadowed, appears to observe the viewer with cautious curiosity, while the right eye, more directly lit, conveys a directness of purpose. Thoma’s lips are pressed lightly together, neither smiling nor frowning, suggesting contemplation. The overall expression avoids theatricality, instead offering an authentic glimpse into the artist’s inner state—a moment of self-awareness rendered with honesty. Through this psychological depth, Thoma transcends mere likeness to create a portrait that functions as both an image and a self-examination.

Technique and Brushwork

Thoma’s technical approach in this work combines precise drawing with painterly restraint. The initial underdrawing, likely executed in fine charcoal or diluted umber, established the contours of the face, hands, and clothing. Over this, Thoma applied a warm mid-tone ground, perhaps a mixture of yellow ochre and sienna, which served as a unifying base. Flesh areas were built through layered glazes: a first layer of transparent rose madder mixed with white provided blush tones, followed by ochre glazes to warm the complexion, and finally white highlights to model the planes of the face. The coat’s texture emerged from broader, opaque strokes of dark umber and black, modulated with thin glazes to suggest fabric folds. Thoma’s disciplined brushwork—smooth in areas of transition, more visible in the beard and hair—creates a surface that is both polished and richly textured.

Symbolic Resonances

While ostensibly a straightforward self-portrait, Thoma’s work also carries symbolic undertones. The dark coat and subdued background may allude to the introspective challenges of the artist’s path, while the direct gaze suggests a commitment to truth-telling in art. The prominence of the beard—an attribute often linked to wisdom and maturity—may hint at Thoma’s evolving self-conception as an artist not merely of technical skill but of thoughtful vision. The choice to paint himself without elaborate attire or props underscores an emphasis on personal authenticity over external status. In this way, the portrait becomes an emblem of the artist’s dedication to sincerity and the inner life as the foundation of creative work.

Relation to Thoma’s Later Work

Comparing the 1873 self-portrait to Thoma’s later allegorical and landscape paintings reveals both continuity and evolution. His early focus on precise form and psychological insight persisted, even as his palette brightened and his subjects expanded to include mythic figures and bucolic scenes. Notably, the careful modeling of light and the tonal harmony achieved here would reappear in his celebrated works such as Allegory of October and Satyr’s Family. However, the self-portrait’s introspective intensity stands apart from the more outwardly symbolic narratives of his mature period. It remains one of the most intimate records of Thoma’s personal and artistic identity.

Reception and Influence

When this self-portrait was first exhibited in Munich, it garnered praise for its technical finesse and the compelling force of the sitter’s expression. Contemporary critics noted the unusual frankness with which Thoma presented himself, avoiding the flattery typical of academic portraiture. Younger artists in Munich looked to Thoma’s blend of academic discipline and personal honesty as a model for their own explorations of individual subjectivity. Over time, the painting has been recognized as a cornerstone of Thoma’s oeuvre, offering insight into the artist’s formative years and his emergent voice within the broader currents of European art.

Conclusion

Hans Thoma’s Self-Portrait from Munich (1873) stands as a landmark in the artist’s development—a work that marries technical mastery with psychological candor. Through a harmonious palette, deft modeling of light and shadow, and a penetrating gaze, Thoma presents not just a likeness but a self-examination. This early self-portrait foreshadows the depth and sensitivity that would characterize his later allegorical and landscape paintings. It remains a powerful testament to the enduring quest of the artist to understand and represent the self, and a compelling invitation for viewers to meet Hans Thoma across the centuries at the level of shared human introspection.