Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

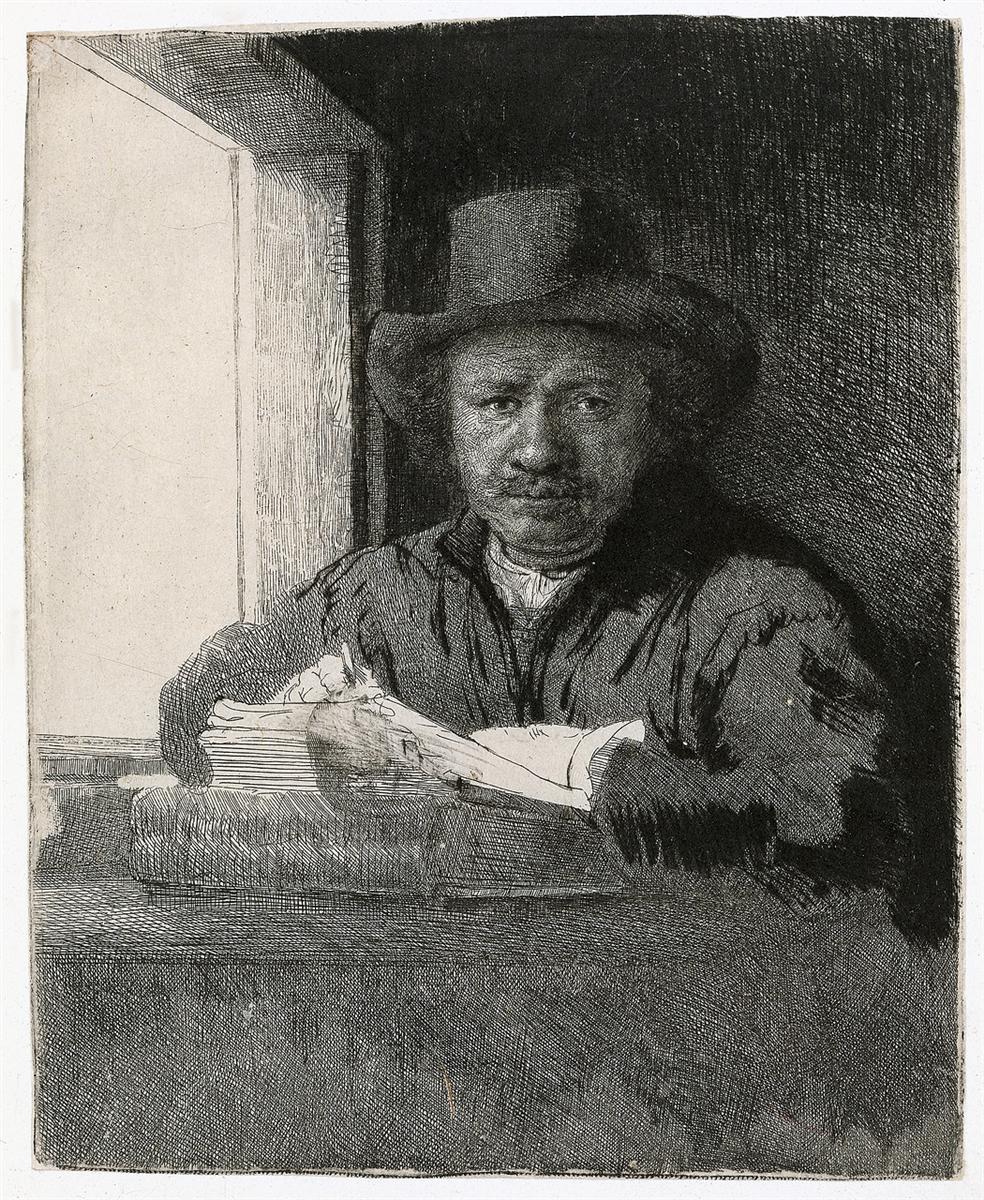

Rembrandt’s “Self-portrait Drawing at a Window” of 1648 is one of the most revealing images the artist ever made of himself at work. Executed as an etching, the print shows the artist seated by a deep, square window, hat on his head, sleeves loose, hands poised over a sheet of paper that lies atop a stack of books or portfolios. He does not dramatize himself as a prodigy or a celebrity. Instead, he presents the ordinary condition of making: light arriving from the left, paper before him, tools in hand, and a mind attentive to the task. The picture looks simple, but it contains a complex meditation on vision, authorship, and the studio’s daily rituals. Line by line, Rembrandt builds a world where the act of drawing becomes the true subject and the window becomes a metaphor for the passage from seeing to making.

The Setting and Its Atmosphere

The room is pared to essentials. The window is a tall, rectangular aperture whose white plane floods the interior with a steady, cool illumination. The deep embrasure and thick wall convey the sense of a solid, urban house in Amsterdam. Inside, the space is densely hatched, the cross-woven strokes turning the right half of the sheet into a soft, absorbent dusk. The table is a blocky slab that anchors the composition and cushions the figure’s presence. There are no ornate props, no trophies, no emblems of celebrity. The studio reads as a working room, and the print’s atmosphere is one of industrious quiet—a silence textured by the scratch of a stylus and the faint shiver of paper under a resting palm.

Composition and the Architecture of Attention

Rembrandt composes the sheet to direct attention to the act of drawing. The window at left supplies a vertical rectangle of light. The artist’s body forms a counter-shape, darker and more compact, pressed up against the light’s edge without stepping into it. His forearms create a low, luminous triangle that culminates in the page. The stack of books or portfolios below the sheet contributes a horizontal mass that stabilizes the hands. Even the hat functions compositionally, building a rounded silhouette that stands out crisply against the cross-hatched background. All of these shapes—rectangle, oval, triangle, slab—funnel the eye toward the paper where the work is happening.

Light, Chiaroscuro, and the Ethics of Seeing

The light in this print has the moral clarity of day. It is not a dramatic spotlight; it is the ordinary illumination of a window, the kind artists and writers have trusted for centuries. It falls strongly on Rembrandt’s face and hands and on the page, while the coat and background sink into a respectful penumbra. Shadows are not theatrical; they are the natural companion of concentration. This distribution of value implies an ethic: the parts of the self engaged in attention—the eyes, the hands, the thinking brow—receive the greatest light. In Rembrandt’s world, light is not merely a physical phenomenon; it is a sign of mind at work.

The Hands and the Grammar of Making

Few images render the working hands with such tenderness. The right hand holds the drawing tool lightly yet decisively; the left, spread across the paper, steadies the sheet and measures proportion. The fingertips press just enough to keep the page from skating; the thumb of the left hand curves into the stack of papers with practiced ease. Rembrandt’s etched line is quick and knowing here, describing bone, tendon, and skin with a minimum of strokes. These are not heroic hands; they are capable hands, remembered from thousands of passes across paper, plate, and canvas. Their choreography is the choreography of thought turning into line.

The Face and the Poise of the Gaze

Rembrandt’s expression is alert, almost quizzical. The eyes meet the viewer’s gaze as if we were the model or reflection he is studying. The mouth is gently set, the mustache catching small highlights where the needle has bitten more deeply. A slight puffiness below the eyes and a compacting of the cheeks signal age and the fatigue of labor, yet nothing about the face reads as complaint. Instead, it communicates that productive mixture of patience and curiosity that sustains long sessions of looking. The brim of the hat casts a band of shadow that pushes the eyes forward, intensifying their focus. The face does not display genius; it practices it.

The Window as Tool and Metaphor

The window does many jobs at once. It is the physical source of light, a kind of North-facing guarantee of steady tonality that painters favored. It is also a frame within the frame, a reminder that vision itself has borders and must be organized. Most suggestively, it is a metaphor for the passage from the exterior world to the interior page. Light crosses the sill to meet the paper; observation crosses the senses to meet the hand. The stone jambs are thick, emphasizing that the passage is real work, as if thought had to push through masonry before it could become form.

Books, Portfolios, and the Studio’s Ecology

Under the drawing sheet lies a stack—perhaps bound portfolios of drawings or prints, perhaps books. Their rectangular weight carries many meanings. They elevate the page to a comfortable height; they signal that this drawing belongs to an ongoing corpus; they connect the present act with a history of study and precedent. Rembrandt etches them with a mixture of precision and speed: close, parallel lines for the fore-edges of paper and wider, slanting hatching for the covers. In the image, knowledge is not an abstraction; it is an object that props the present moment of work.

Line, Plate Tone, and the Music of the Etching

As an etching, the print demonstrates a full orchestra of marks. The background is a weave of long, nearly vertical strokes that thicken into a breathable black; the table and books are organized by broader, horizontal cuts; the figure’s coat is built from interrupted hatching that suggests soft, worn cloth. Rembrandt leaves the window and the paper almost free of lines, letting the untouched plate print as light. In some impressions, a thin veil of plate tone remains, especially near the window embrasure, adding an atmospheric softness that acts like air between the figure and the wall. The effect is not merely visual; it is auditory. The sheet “sounds” differently across its fields—the window a quiet held note, the background a low hum, the hands a quick, articulate solo.

Process, Self-Representation, and Truthfulness

This self-portrait does not advertise status, as some earlier painted portraits do with chains, gloves, or costly fabrics. Nor is it comic or theatrical, like Rembrandt’s youthful tronies in exotic hats. It is a portrait of process. The artist chooses to show himself in the act that generates everything else. That choice carries an ethic of truthfulness: the public image becomes the private habit of work made visible. We are not treated to the finished product but to the practice that makes finished products possible. This is the humility of mastery, not its denial.

The Hat and the Economy of Costume

The wide-brimmed hat is the print’s only flourish, yet even it is practical. It shades the eyes, reducing glare from the window and sharpening contrast on the page. Its rounded form also organizes the head’s silhouette against the dark background, ensuring that the face reads clearly across the room. Etched with swift cross-strokes, the hat feels light but sufficient, a working accessory rather than a theatrical prop. The coat, too, is a painter’s garment—ample in the shoulders, loose at the wrists, ready to tolerate smears of chalk or ink.

The Viewer’s Position and the Dynamics of Looking

We stand where the subject of the drawing would stand—slightly to the left of center, within the cone of light thrown by the window. This clever positioning makes the viewer complicit in the act of making. Are we the model? A reflection in a mirror? Or an imagined interlocutor, a presence the artist invokes to keep his eye sharp? The ambiguity is productive. It blurs boundaries between sitter and seer, between object and maker, inviting us to inhabit the studio space not as voyeurs but as collaborators in vision.

Time, Suspense, and the Threshold of the Mark

One of the print’s quiet thrills is the way it suspends time. Rembrandt has caught the moment just before a line is laid down. The right hand hovers; the left pins the page; the face calibrates. The etching therefore becomes a portrait of potential energy. The long, dense hatching everywhere else slows our eye so that we can feel this poised instant. In that slowness we recognize the rhythm of studio life: look, measure, place the line, repeat. The print keeps us inside that loop.

Comparisons within Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits

Throughout his career, Rembrandt used self-portraiture to probe identity, age, and artistic calling—from youthful masquerades to late, unsparing canvases. This 1648 image lies at the center of that arc. It lacks the theatrical bravura of early tronies and the tragic grandeur of late oils, choosing instead a middle key of steady craft. It pairs naturally with his other depictions of the studio from the same period, including prints where a model stands at a window and the draughtsman sits nearby. Together they develop a philosophy: art is not the exception to daily life; it is a disciplined daily life.

Technique Across Impressions and the Performance of Printing

Rembrandt often printed his plates with varied wiping, leaving more or less plate tone to modulate atmosphere. In some early, rich impressions of this self-portrait, the background feels almost velvety, the window brighter by contrast and the face emerging with pearl-like luminosity. Later, cleaner pulls can sharpen detail in the sleeves and hat, shifting the balance toward linear description. This variability makes each impression a performance—another session by the same musician playing the same score with slightly different dynamics. The printing itself becomes a second act of drawing.

The Studio as Civic Space

Although intensely private, the scene carries a public meaning. Amsterdam in the mid-seventeenth century valued industriousness and skill; Rembrandt presents the artist’s work as a craft among other crafts, requiring tools, light, and patience. No exoticism is required to justify the vocation. The window opens not onto a view but onto light itself, implying that the city’s true resource is the clarity it affords to those who labor. The studio is not a temple; it is a room where work happens, and in that ordinariness lies a democratic claim for art’s place in civic life.

Materiality, Memory, and the Life of the Plate

Look closely and the plate remembers the artist’s hand. A slightly heavier bite along the outer contour of the hat, a tremor in the line that marks the collar, a few accidental scratches near the window jamb—these tiny incidents become part of the image’s personality. They remind us that an etching is not a transparent window onto the world but a thing with a history: copper, ground, needle, acid, ink, paper. The portrait is a likeness of a person and a self-portrait of a process. When we attend to those marks, we participate in the memory the plate has stored.

Legacy and Continuing Appeal

“Self-portrait Drawing at a Window” remains a touchstone for artists and viewers because it captures the intimacy of making without romanticizing it. Students learn from its economy of means, its command of value, and its quiet insistence on the primacy of the hand. Curators use it to introduce audiences to the poetics of etching and to the way Rembrandt transformed a reproductive medium into a field of invention. For anyone who writes, designs, codes, or crafts, the print offers a familiar scene: a person, a source of light, a surface, and the patience to bring thought into form.

Conclusion

In this 1648 etching, Rembrandt turns the humble act of drawing into a manifesto about seeing. The window’s clear light, the practiced hands, the suspended moment before a line descends—all reveal a vision of art as attention embodied. Without props or theatrics, the image gives us the dignity of work and the intimacy of a mind in the midst of making. It is a self-portrait of vocation rather than vanity, and it continues to feel contemporary because the conditions it depicts—light, paper, and discipline—have not changed. The artist looks up from his page; we meet his gaze; and for a moment, the window between worlds is simply open.