Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Saint-Rémy and Van Gogh’s Self-Reflection

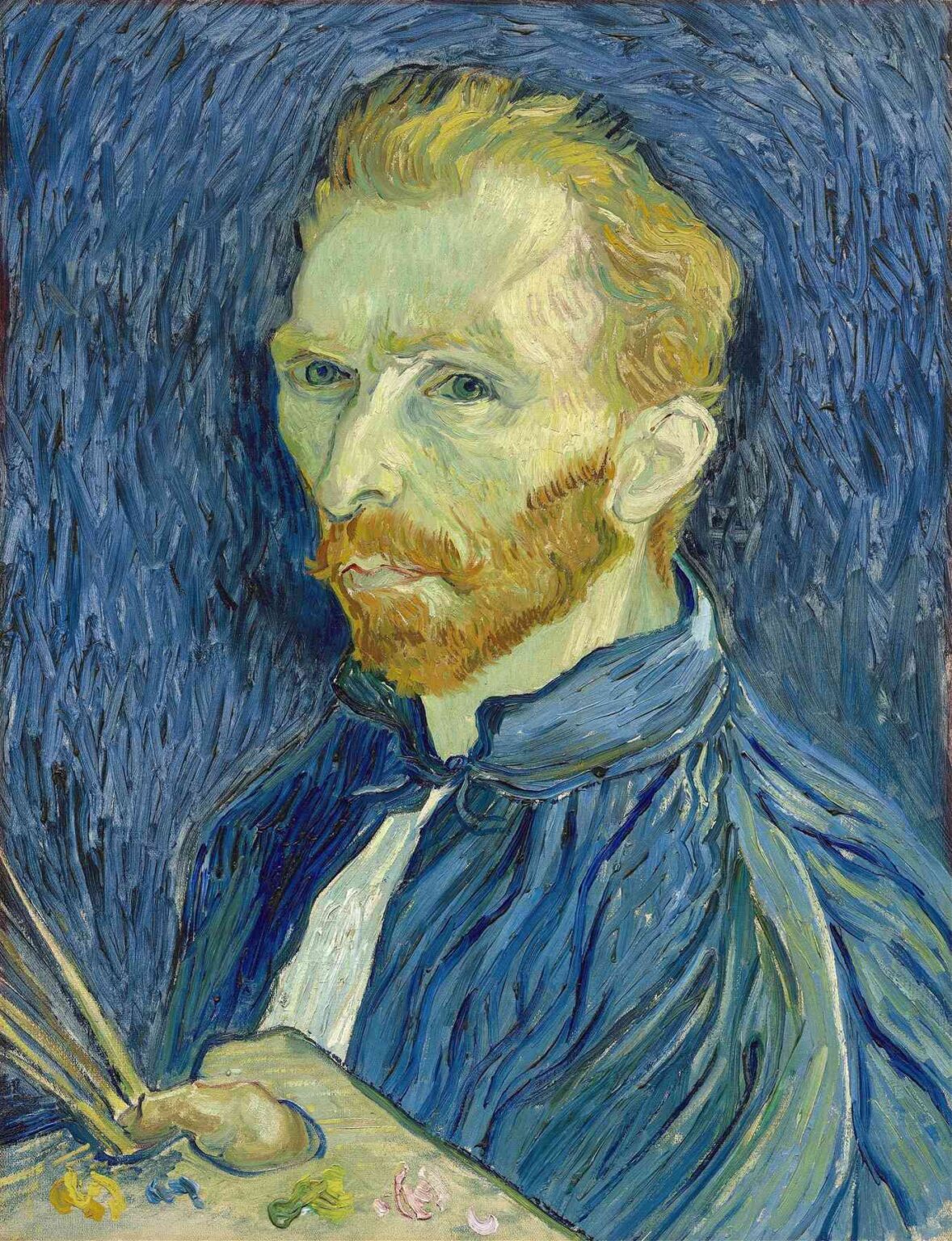

In May 1889, Vincent van Gogh voluntarily admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, seeking respite from the mental crises that had plagued him since Arles. Surrounded by cypress trees, olive groves, and fields of wheat, he found both torment and inspiration in equal measure. During his year-long stay, he produced some of his most emotionally charged and technically bold work. Painted in September of that year, “Self-Portrait” (1889) emerges from this crucible of introspection. At a time when Van Gogh wrote candidly to his brother Theo about his struggles and hopes, this canvas serves as a mirror not only of his appearance but of his psyche—capturing an artist in the throes of self-examination amid a landscape that alternately soothed and unsettled him.

The Artist as Sitter: Van Gogh’s Psychological Presence

Rather than commissioning a portrait from a sitter, Van Gogh turned the brush upon himself in a radical act of self-disclosure. His penetrating green eyes fix the viewer with an intensity that belies his fragile condition. The gaunt cheeks, sinewy neck, and slightly furrowed brow offer clues to the physical and mental strain he endured. Yet these features are rendered through a chromatic vocabulary that transcends mere likeness. The neon-green undertones in the face, juxtaposed with electric blues in the hair and cloak, transform the self-portrait into a study of psychological tension. Van Gogh does not shy away from exposing his vulnerability; instead, he makes it the focal point of a composition that pulsates with inner unrest.

Composition: Tilted Framing and Dynamic Lines

“Self-Portrait” adheres to a composition that is simultaneously conventional and experimental. The artist’s head and shoulders dominate the canvas, slightly turned to the left, while the easel edge and lower palette project diagonally from the bottom left corner. These elements create a sense of leaning motion—as if Van Gogh is emerging from the painting toward the viewer. He sets himself against a background of swirling blue brushstrokes, which radiate outward like an aura. This network of lines forms a halo of motion around the tightly controlled figure, anchoring the portrait’s vertical axis. The interplay of diagonal and vertical dynamics imbues the work with a restless energy reflective of the artist’s tumultuous inner world.

Palette and Color Psychology: Blue, Green, and Yellow

Throughout his career, Van Gogh associated colors with emotional states: blue for melancholy, green for renewal, yellow for vitality. In this self-portrait, he orchestrates a symphony of cool-blue brushstrokes in the background and cloak, inflected by touches of deep ultramarine and cerulean. These hues convey a sense of introspective calm, yet the frenetic motion of the strokes suggests undercurrents of agitation. His face, a mix of pale greens and yellow-tinged whites, glows with an otherworldly light, placing his features somewhere between life and vision. Accents of cadmium yellow in the hair and beard break the chromatic unity with a spark of warmth, hinting at the artist’s enduring creative flame despite his psychological distress.

Brushwork and Impasto: Texture as Emotional Expression

Van Gogh’s brushwork in this portrait exemplifies his late style: thick, directional impasto that sculpts form while articulating feeling. Each stroke in the background curves and flows, building a kinetic field that envelops the sitter. His hair and beard are rendered with shorter, more controlled dabs, yet the paint remains generously applied, creating a tactile surface that catches light from multiple angles. Even the palette at the bottom, with its blobs of mixed pigments, becomes an extension of the artist’s gesture—a tangible record of color experimentation. Through the language of impasto, Van Gogh communicates not only form but psychological resonance, as each ridge and furrow of paint echoes the tremors of his spirit.

Light, Shadow, and Spatial Ambiguity

Traditional portraiture relies on chiaroscuro to model three-dimensional form, but Van Gogh here approaches light through hue contrasts rather than tonal gradations. The right side of his face is built from warmer whites and yellows, advancing toward the viewer, while the left side recedes into cooler greens and blues. Shadows are painted without pure black, composed instead of deep cerulean mixed with burnt sienna, preserving a vibrant chromatic integrity. The background’s single color family flattens spatial depth, yet the directional quality of the strokes suggests atmospheric undulation. The result is an image that exists between relief sculpture and decorative panel—challenging viewers to reconcile illusion with the material presence of paint.

Psychological Resonance: Confrontation and Vulnerability

Van Gogh’s gaze is at once defiant and vulnerable. His eyes, rendered in shimmering greens and blues, lock onto our own, implicating the viewer in an act of psychological communion. The slight downturn of the mouth and the firm set of the jaw convey both determination and weariness. In his Saint-Rémy letters, he confessed a longing to transcend his suffering through art; this self-portrait can be read as both testament and vow. It proclaims, “Here I am, in all my fragility, wielding color and brush as shields and confessionals.” The encounter with this painted gaze can provoke empathic response, mirroring the empathetic intensity Van Gogh sought in his own relationships.

Relation to Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait Tradition

By 1889, Van Gogh had painted over thirty self-portraits, beginning in Paris and through Arles into Saint-Rémy. Early Paris self-portraits are characterized by dark backgrounds and somber palette, reflecting his explorations of tonalism. In Arles, he experimented with brighter color and light within the self-portrait genre, often donning a straw hat or seated before a window. The Saint-Rémy version distinguishes itself through its dramatic background rhythm, electric greens in the visage, and the inclusion of the palette and brushes—a meta-commentary on the act of painting itself. It synthesizes his formal advances with his psychological narrative, making it a pivotal work in his self-portrait oeuvre.

The Palette and Brushes as Symbolic Props

Unlike more austere self-portraits, Van Gogh includes his painter’s tools in the composition. The palette, with dollops of white, green, yellow, and pink, along with three brushes held gently in his left hand, emphasize the medium through which he navigates his inner life. The small array of pigments reflects his limited resources at Saint-Rémy and underscores his resourcefulness in mixing hues for varied emotional impact. These elements serve as extensions of the sitter’s identity: he is both subject and creator, inseparable from the implements of his craft. By placing them within view, Van Gogh elevates the act of painting to a spiritual gesture, a means of surviving internal storms.

Provenance and Exhibition History

Following Van Gogh’s tragic death in July 1890, the self-portrait passed to his brother Theo, who briefly owned it before it entered the collection of Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard. From there, it was acquired by private collectors and exhibited in early Post-Impressionist shows across Europe. By the mid-twentieth century, it had become a prized highlight in major museum exhibitions dedicated to Van Gogh’s self-portraits and Saint-Rémy period. Each curatorial context—from national retrospectives to modal exhibitions on mental health and art—has emphasized different facets of its complexity, ensuring its place as one of the most scrutinized and beloved depictions of the artist.

Technical Examination and Conservation Insights

X-ray fluorescence analysis reveals Van Gogh’s pared-down Saint-Rémy palette: lead white, cadmium yellow, emerald green, Prussian blue, and a trace of vermilion for flesh tones. Infrared reflectography shows minimal underdrawing, indicating he sketched the composition lightly or began directly with paint. Conservation reports note fine craquelure in the thick impasto regions, especially in the background and beard, consistent with rapid drying in the Provençal climate. Recent cleaning removed discolored varnish layers, restoring the luminosity of the blues and greens and revealing subtler transitions in the model’s cheek and temple areas that had been obscured for decades.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretation

Early critics were fascinated by the self-portrait’s electric palette but puzzled by its departure from academic convention. By mid-century, art historians hailed it as proto-Expressionist, a key influence on Fauvist and German Expressionist artists who admired its emotive color and rhythmic brushwork. Psychoanalytic readings of the 1970s examined it as a document of mental illness and creative resilience. More recent scholarship explores the painting through neuroaesthetic frameworks, studying how the brain responds to its swirling textures and direct gaze. Each interpretive wave has deepened our understanding of how Van Gogh fused technique and feeling to create a self-portrait that remains profoundly moving.

Legacy and Influence on Self-Portraiture

Van Gogh’s “Self-Portrait” (1889) stands as a milestone in the history of portraiture and psychological self-exploration. Its influence resonates in twentieth-century art—from the Expressionist self-portraits of Edvard Munch to the color-field experiments of Mark Rothko and the gestural canvases of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Contemporary artists continue to reference its bold use of color, its integration of tools, and its willingness to bare inner turmoil. In popular culture, reproductions of the 1889 self-portrait appear on book covers, album art, and fashion spreads, often invoked to symbolize the nexus of creativity and vulnerability.

Conclusion: A Masterpiece of Inner Vision

In his 1889 self-portrait, Vincent van Gogh transforms the canvas into a confessional space, melding formal innovation with raw emotional candor. The vibrant interplay of blue, green, and yellow, the dermal impastos, and the direct, unflinching gaze coalesce into an image that transcends time and place. Here, Van Gogh confronts his own fragility and asserts the transcendent power of art to channel suffering into beauty. As viewers, we are drawn into his world, compelled to recognize our own reflections in the swirling lines and radiant hues. This self-portrait remains a testament to the inseparable bond between an artist’s interior life and the imagery that endures across centuries.