Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Paris and the Artistic Milieu of 1887

By early 1887, Vincent van Gogh had relocated from the rural quiet of Nuenen to the bustling heart of Paris, seeking to immerse himself in the vibrant avant-garde. The French capital was then in thrall to Impressionism’s dissolution of form, Symbolism’s exploration of inner life, and emerging Neo-Impressionist experiments in color theory. Van Gogh lodged with his brother Theo in Montmartre, where studios and cafés teemed with painters such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Signac. Here, he first encountered Georges Seurat’s pointillist technique and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s candid portrayals of modern life. In this charged atmosphere of innovation, Van Gogh began to recalibrate his palette—trading the earth tones of his Dutch period for luminous pinks, violets, and greens. It was against this backdrop of restless creativity that he painted the 1887 Self-Portrait, a work that both absorbs and reacts to Paris’s electric energy.

Van Gogh’s Paris Self-Portrait Tradition

Prior to 1886, Van Gogh had created only a handful of self-portraits, primarily studies in charcoal and muted oil sketches. In Paris, however, he embraced the genre as a laboratory for his evolving style. Over three years, he produced more than a dozen paintings of himself, each reflecting shifts in technique, color, and psychological focus. The 1887 Self-Portrait belongs to a series that displays his dialogue with Impressionism and Divisionism. Unlike his earlier depictions—heavy with rustic solemnity—this canvas reveals a newfound confidence in bold hue contrasts and patterned brushwork. The Self-Portrait thus occupies a pivotal position: it bridges the brooding introspection of his Nuenen era with the expressive flamboyance that would define his later Arles and Saint-Rémy masterpieces.

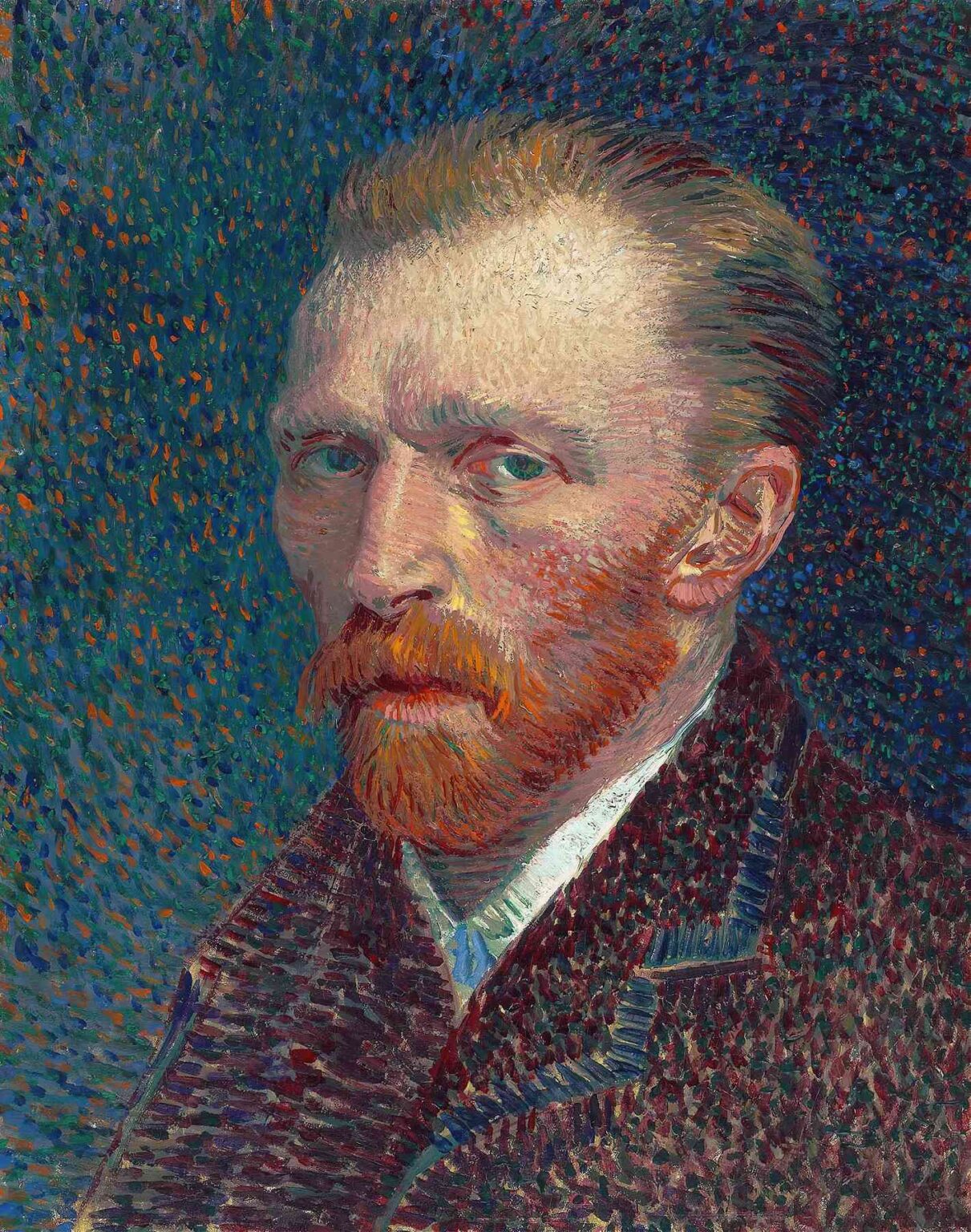

The Artist as Sitter: Appearance and Persona

In this 1887 painting, Van Gogh presents himself in half-length, roughly waist up, gazing directly at the viewer with unwavering intensity. His hair and beard, trimmed compared to the wild mane of Arles, are rendered in shades of auburn and sienna, suggesting both control and restless energy. He wears a dark jacket over a crisp white shirt, the collar peeking above a loosely knotted necktie. Unlike portraits commissioned by patrons, Van Gogh’s choice of attire feels part personal statement, part painterly device: the dark jacket offers a foil for his kaleidoscopic skin tones, while the white shirt captures residual light, framing his face. Through this sartorial arrangement, he negotiates the tension between the public persona of the artist and his private vulnerabilities.

Composition and Framing: Engaging the Viewer

Van Gogh positions himself at a slight angle, shoulders tilted to the left as his head turns back toward the spectator. This subtle twist creates a dynamic diagonal that activates the composition. His face hovers near the vertical center, while a loosely indicated easel edge and palette brush stroke appear at the painting’s lower right—reminders of the act of creation. There is no elaborate background setting: instead, an undulating field of virescent greens and soft pinks suggests a studio wall or abstract atmosphere. By cropping close and omitting extraneous detail, Van Gogh enacts a psychological immediacy: the viewer feels as though they stand mere inches from the canvas, confronted by both the image and the man behind it.

Palette and Color Theory: Experimentation with Hue

A hallmark of Van Gogh’s 1887 work is his radical embrace of complementary color juxtapositions. In this Self-Portrait, flesh tones shift from warm ochres to cool greens, reflecting his absorption of Signac’s Divisionism and Seurat’s scientific approach to optical mixing. The background oscillates between flecks of emerald, viridian, and soft rose, creating a vibrating field that makes the figure advance toward the eye. Scarlet accents in the beard and hairline resonate against the turquoise undertones in the shadows. These deliberate contrasts heighten emotional resonance: warm notes convey vitality and passion, while cool tints evoke introspection. Through this chromatic symphony, Van Gogh transforms a simple likeness into a study of color’s capacity to articulate feeling.

Brushwork and Technique: From Impasto to Divisionist Influence

Unlike the thick impasto of his later Arles paintings, Van Gogh’s 1887 Self-Portrait reveals a lighter touch, yet still teems with energy. He applies paint in short, hatched strokes that weave across the canvas like fabric threads. In the jacket, swift vertical lines build a textured surface, while in the face, diagonal hatching sculpts planes of light and shadow. This approach reflects his Parisian experiments with Divisionist methods—deploying dots and dashes of pure pigment that blend in the viewer’s eye. Yet Van Gogh never abandoned his painterly bravura: individual strokes retain a tactile quality, inviting close inspection. The result is a portrait that fuses methodical color theory with impassioned gesture, a signature of his evolving style.

Light, Shadow, and Spatial Treatment

Rather than relying on a single directional light source, Van Gogh models form through strategic shifts in hue. The right side of his face is built from soft pinks and creams, while the left recedes into cooler greens and lavenders. Shadows are not rendered with gray or black but with complementary mixtures—green beneath the jawline, violet at the temple—preserving the vibrancy of each color field. The absence of cast shadows behind the figure flattens the spatial depth, aligning the portrait with the decorative flatness of Japanese prints he collected. Yet within this shallow space, Van Gogh conjures believable volume through chromatic modulation, demonstrating that light need not be simulated by value alone.

Psychological Insight and Expression

The 1887 Self-Portrait transcends mere likeness to become a psychological study. Van Gogh’s eyes, rendered in pale blues flecked with rose, engage the viewer with a blend of vulnerability and resolve. Their directness betrays neither despair nor triumph but an open query: he seems to ask, “Do you see me as I am?” The furrowed brow and slightly pursed lips hint at inner turmoil, yet the controlled palette and measured brushwork suggest composure. In letters to Theo, Van Gogh wrote of painting portraits to understand both others and himself; here, he uses the canvas as a mirror, probing his own emotional landscape and inviting empathetic exchange.

Relation to Contemporary Avant-Garde Trends

Van Gogh’s 1887 Self-Portrait stands at the crossroads of several avant-garde currents. His incorporation of small, directional strokes nods to Neo-Impressionist color theory, while his flattened space and rhythmic surface evoke Japonisme’s decorative sensibility. The subdued impasto recalls the refined tactility of John Russell, an Australian painter he admired in Paris. Yet Van Gogh’s chromatic boldness and emotional candor push beyond mere imitation, forging a personal language that would inform the expressive force of Post-Impressionism. In this portrait, he synthesizes diverse influences into an innovative formal grammar, marking a turning point in modern art.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After its completion in mid-1887, this Self-Portrait remained with Van Gogh until his departure for Arles in 1888. Following his death in 1890, the portrait passed to Theo, who briefly exhibited it in Paris before bequeathing it to Jo van Gogh-Bonger. During the late 1890s and early 1900s, it was shown in Amsterdam and Brussels, contributing to the artist’s posthumous reputation. By the 1920s, the painting entered the collection of a prominent European museum, where it has since featured prominently in retrospectives of Van Gogh’s Paris years. Each exhibition has underscored the work’s pivotal role in the transition from Impressionism to Post-Impressionism.

Technical Examination and Conservation Insights

Recent technical studies confirm Van Gogh’s use of a sparse but potent palette: lead white, cadmium yellow, cobalt blue, emerald green, and madder lake. Infrared reflectography reveals minimal underdrawing, indicating that Van Gogh sketched his own visage quickly, relying on paint to capture lifelike detail. Micro-XRF analysis shows traces of Prussian blue in the background strokes, enhancing their depth. Conservation records note that the paint layer has remained remarkably stable, with fine craquelure following the hatched brushwork patterns. A careful 21st-century cleaning removed discolored varnish, restoring the original luminosity of Van Gogh’s carefully calibrated hues.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Debate

Early critical response to the 1887 Self-Portrait was muted, overshadowed by Van Gogh’s darker themes and rural scenes. Mid-twentieth-century scholars reappraised it as a crucial example of his Parisian breakthrough, highlighting its coloristic innovations and formal synthesis. Feminist and postcolonial critics have since explored how Van Gogh’s self-portrayal negotiates identity against a backdrop of European artistic appropriation of Japanese art. Neuroaesthetic researchers are now examining how viewers respond physiologically to the portrait’s textured surface and direct gaze. Across these debates, the painting endures as a rich site for inquiry into the intersections of technique, psychology, and cultural exchange.

Legacy and Influence on Portraiture

The 1887 Self-Portrait has exerted a lasting influence on generations of artists seeking to fuse color theory with emotional immediacy. Early Expressionists drew inspiration from Van Gogh’s chromatic audacity, while later modernists saw in his fusion of flat patterning and impasto a precursor to abstraction. Contemporary painters continue to reference the Paris series when exploring the self as subject and medium. The portrait’s cropped composition, rhythmic strokes, and layered hues resonate in countless homages, testifying to Van Gogh’s role as a pioneer of modern self-portraiture.

Conclusion: A Mirror of Modern Consciousness

Vincent van Gogh’s 1887 Self-Portrait stands as a testament to an artist at the threshold of modernism. Through a daring palette of contrasting hues, dynamic brushwork influenced by Divisionism, and a composition that collapses space, he transforms the act of self-representation into a profound psychological inquiry. The painting captures both the external trappings of Parisian life and the inner journey of a man grappling with identity, ambition, and vulnerability. More than a likeness, it is an archive of creative exploration—a mirror of modern consciousness that continues to challenge and inspire viewers more than a century later.