Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

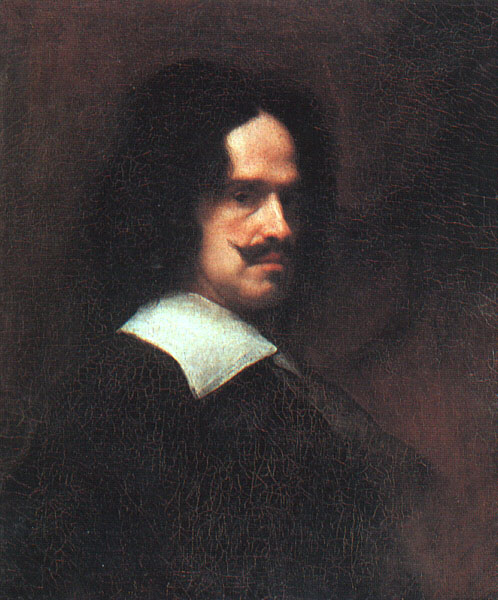

Diego Velazquez’s “Self-Portrait” of 1643 is a compact, arresting statement of artistic identity during the heart of his Madrid career. The painting shows the artist in three-quarter view, emerging from a penumbral background with a crisp white collar that flashes like a wedge of light beneath his face. The head turns slightly, the moustache curves with sculptural certainty, and the gaze holds the viewer with a mixture of scrutiny and reserve. Nothing distracts—no studio props, no allegorical attributes—so the entire burden of meaning rests on light, tone, edge, and presence. In this economy, Velazquez demonstrates the same authority he brought to kings, philosophers, and jesters: a conviction that truth in portraiture arises when paint becomes a precise form of attention.

Historical Moment and Purpose

By 1643, Velazquez had served Philip IV for more than a decade. He had traveled to Italy, absorbed Venetian color and Roman gravitas, and returned to Madrid with a deepened command of atmosphere and restraint. Within the ceremonial machinery of the Habsburg court, the painter occupied a paradoxical place—both servant and arbiter of appearances. A self-portrait from this period is therefore never just a likeness; it is an argument about status. Velazquez shows himself as a gentleman rather than a craftsman, dressed in sober black with a starched collar, yet he eschews all rhetorical accessories. The authority we register comes from the painter’s seeing, not from emblems, and that is precisely the point.

Composition and the Geometry of Attention

The composition leads the eye with quiet force. The torso turns away while the head pivots back toward the viewer, creating a hinge at the neckline where the collar’s triangular plane projects like a platform. That pale wedge is the painting’s anchoring geometry, catching the light and throwing it up toward the face. The rest of the field retreats into deep, breathable shadow. This orchestration concentrates attention on the forehead, cheekbone, and upper lip—those planes where illumination explains form with the fewest strokes. The silhouette of hair provides a soft halo that seals the head against the darkness without hard outline, a method that produces presence rather than cut-out.

Light, Palette, and Atmosphere

The palette is disciplined to blacks, umbers, olive browns, and the cool whites of collar and reflected highlights. Light comes from high left, glancing off the brow, riding the ridge of the nose, and kindling the white collar. Rather than modeling with strong contrasts, Velazquez builds flesh from small temperature shifts: warm ochres against cooler gray-greens, transparent half-tones sliding into shadow. The background is not a flat wall but a chamber of air where edges drift, an atmosphere that lets the head seem to breathe. The restraint of color makes tone do the expressive labor, a hallmark of the painter’s mature manner.

The Face and the Intelligence of the Gaze

The psychological center is the gaze—steady, unhurried, and exact. One feels the professional’s appraisal: a man who has weighed hundreds of faces now weighs his own and ours at once. The lids are slightly heavy, the pupils small points of wet light, the mouth sealed in a neutral line that declines both smile and severity. Nothing is dramatized. Velazquez refuses the theatrical chiaroscuro of self-fashioning and offers instead the self-possession of a mind at work. The moustache, sharply notched, becomes a sculptural punctuation that stabilizes the lower half of the face and returns rhythm to the arc of the collar.

The Collar as Visual and Social Device

Spanish portraiture of the period often makes the golilla collar a declarative shape, and Velazquez uses it here both structurally and symbolically. Structurally, its pale triangle is a reflector that throws light under the chin and separates head from body, allowing the torso to melt into darkness while the face remains legible. Symbolically, the collar signals the dignity of the sitter’s station. No palette, no brushes are needed; this controlled plane of white says that the painter claims the deportment of a gentleman, his rank built from the acuity of his craft rather than the trappings of a workshop.

Brushwork and the Art of Suggestion

Up close, the painting resolves into a grammar of strokes. The hair is indicated by supple, dark sweeps that thicken where locks catch light and dissolve where they merge with background. The flesh is laid in with thin, elastic veils whose edges are softened just before they meet shadow, producing the sensation of living skin. The collar’s whites are brisk and slightly impasted, their crispness contrasting with the soft transitions above. Velazquez’s economy is absolute: describe only what the eye requires and let the viewer complete the rest. That invitation to co-author the image is part of the portrait’s modernity.

Silence, Reserve, and the Ethics of Self-Presentation

Many self-portraits advertise the studio—palettes, easels, canvas-within-canvas—so that the painter can stage virtuosity as narrative. Velazquez refuses the boast. His reserve is ethical: the work of painting should be legible in the manner of the paint, not in the enumeration of tools. The silence of the background and the spareness of the composition compel a different kind of attention. We encounter the person who looks before we contemplate the person who performs, and that order of operations mirrors the discipline of his art.

Time, Labor, and the Texture of Truth

The surface carries a quiet record of time. Thin passages allow the weave of the canvas to pulse through the paint, while small ridges along the collar catch light like cresting waves. These traces speak of labor without ostentation. The illusion of flesh, hair, and air does not attempt to conceal its manufacture; it reveals just enough of its making to remind us that seeing is constructed with effort. In a courtly culture of polished appearances, this modest revelation of process reads as a kind of honesty.

A Dialogue with Other Self-Images

Compared with the self-portrait around 1640—closer, more frontal, the collar sharper—this 1643 image is softer and more atmospheric, the head pushed slightly deeper into space. It feels less declarative and more contemplative, as though the painter has stepped a pace back from the viewer and from the urgency of self-assertion. Later, in “Las Meninas,” Velazquez will embed his self-image within the act of painting, turning self-portraiture into a meditation on perception. The 1643 head is a bridge between those modes: private and distilled, but charged with the same questions about who looks, who is looked at, and how images construct truth.

Presence Without Rhetoric

The portrait’s strength is the absence of rhetorical flourish. No allegory labors to glorify the sitter; no motto declares program. Instead, presence is built from three elements—light, tone, and edge—handled with such authority that the small canvas occupies space like a person. The viewer’s response is calibrated—not awe before spectacle, not familiarity before a snapshot, but a lucid regard before a mind that returns our look. In this balance lies the secret of Velazquez’s portraits, whether of kings, jesters, or himself.

The Viewer’s Position

We stand slightly below the eye line, a subtle elevation that confers dignity without arrogance. The head’s turning keeps the pose alive and prevents stasis, while the collar’s flare establishes a little architectural ledge between us and the sitter, as if the portrait protected a perimeter of privacy. The point of view ensures equality rather than hierarchy: neither courtier nor suppliant, the viewer is invited into a conversation of looking where attentiveness is the currency.

Influence and Afterlives

Painters after Velazquez learned from this containment. Goya found in it a model for psychological candor set in breathable darkness; Manet and Sargent took from it the courage to let paint remain paint while conjuring presence; even photographers have borrowed the lesson that a dark ground, a single plane of light, and an unforced expression can carry extraordinary weight. The 1643 “Self-Portrait” endures because it aligns virtuosity with reticence, insisting that clarity—not embellishment—is the highest form of display.

Why This Image Still Feels Contemporary

Standing before the painting, one senses how uncluttered it is by period rhetoric. The cut of clothing and the moustache are seventeenth-century, but the encounter is modern: a person, alert and intelligent, occupying a space of shadow and light. The portrait trusts perception rather than symbol, and that trust feels contemporary because it respects the viewer’s intelligence. We are asked to read tone, temperature, and gesture; to register small decisions rather than grand pronouncements; to recognize, finally, a self fashioned by attention.

Conclusion

The 1643 “Self-Portrait” is a lesson in the power of understatement. Velazquez builds identity from a handful of tones, a wedge of white, and a gaze that refuses both flattery and theatricality. In the hush of this dark room, he sets forth an image of the painter as a gentleman of perception, whose authority flows from the steadiness of his looking. The painting is small, but it contains the grammar of his art: atmosphere, economy, empathy, and an unshakable belief that presence can be conjured without noise. Four centuries on, the portrait still meets us with unspent clarity, reminding us that the greatest bravura in portraiture is the courage to say only what is necessary.