Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

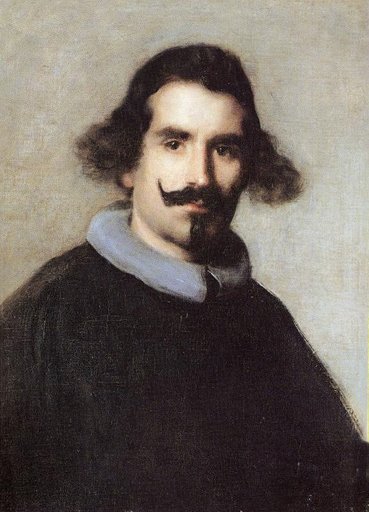

Diego Velázquez’s “Self-Portrait” is a quiet manifesto. Painted during his first Italian sojourn, it strips the language of court portraiture down to its most persuasive elements—air, light, and the human face—then turns those tools back upon their owner. The artist presents himself at half length against a plain ground, shoulders slightly angled, a soft collar catching light beneath a dark cloak, and a face that balances candor with reserve. The hair flares lightly at the sides, stirred by the same air that seems to circulate around the head. Nothing distracts: no attributes, no studio props, no Latin mottoes. The picture is a meeting, not a monument, and it tells us as much about Velázquez’s ethics as a painter as it does about his features.

Historical Context

By 1630 Velázquez had been at the court of Philip IV for nearly a decade and was in Italy to study antiquity and living masters. Rome and Naples offered him Titian’s color, Caravaggio’s gravity, and the precision of antique sculpture. At the same time he was consolidating a new Spanish sobriety in portraiture—one that traded heraldic noise for the rhetoric of atmosphere. A self-portrait painted in this moment is more than a likeness; it is a statement of method. The artist who could dignify kings and jesters with the same accurate light now submits his own face to the test. No painterly bravura, no theatrical contrivance: the image proposes that truthfulness itself is the highest decoration.

Composition and Pictorial Architecture

The composition is a stable triangle. The head occupies the apex, the broad dark costume forming the base. Velázquez turns the body quietly to one side and lets the head return toward us, a classic device that supplies both dynamism and decorum. The background is a warm, breathable gray that darkens imperceptibly at the outer edges, coaxing the viewer’s attention inward without resorting to vignetting. The collar—cool, almost silvery—creates a gentle interval between face and cloak, while the hair’s outward sweep broadens the silhouette at the top, keeping the triangle from feeling heavy. Everything is poised, nothing forced; the design whispers confidence.

Light and Chiaroscuro

Light enters from the left with judicial calm. It travels across the brow, rides the bridge of the nose, and settles in half-tones around mouth and chin before fading at the jaw. This is daylight rather than stage light, the kind that makes forms plausible and skin breathable. There are no black pits in the shadows; instead, value steps down in small intervals that keep volume intact. The background receives light as air, not as wall. The result is a head that seems to sit in real space rather than on the surface of the panel. With the simplest means Velázquez demonstrates the grammar he would later deploy on a grand scale: let light carry character, and let character carry everything else.

The Face and Its Psychology

Velázquez’s face is austere and alert. The eyes are set with a few telling touches—dark irises, a glint that pivots the gaze outward, a sober ring of lower lid. The nose is modeled with a single decided transition, and the mouth is held in a line that avoids both severity and softness. The mustache and small pointed beard assert a fashionable elegance without vanity. What registers most, however, is attention. The painter looks in the direction of the viewer but not quite at us, as if he were assessing light rather than human company. It is the psychology of work: reserved, curious, and unsentimental. Portraits of monarchs show restraint because protocol demands it; the restraint here is self-governed and therefore more revealing.

Hair, Collar, and the Play of Edges

The hair is not a sculpted helmet but a field of quick, animated strokes, the sides lifted slightly by movement in the air. This flutter keeps the silhouette lively and sets off the stillness of the face. The soft, cool collar carries much of the picture’s formal rhetoric. It brightens the lower register, separates flesh from costume, and gently echoes the oval of the head. Its edges are sharp where light clicks on starched cloth and dissolved where form turns into shade. Those modulations of edge—crisp, softened, or lost—are the painter’s real signature. They allow him to state firmness without stiffness and atmosphere without blur.

Palette and Emotional Temperature

The picture’s color is Spartan: blacks and near-blacks for the garment, a cool gray-blue for the collar, warm flesh notes held in restraint, and a neutral ground. Within this narrow scale, Velázquez creates harmonies that feel inevitable. The collar’s coolness throws warmth into the face; the cloak’s deep value allows small highlights on the cheek and nose to carry more weight; the background receives just enough warmth to keep the whole from chilling. The temperature of the portrait is candid and serious—neither courtly pomp nor bohemian swagger—perfect for a self-declaration of craft.

Brushwork and the Art of Decision

Everywhere the paint is economical. Flesh is built from semi-opaque strokes that merge into a living surface; the eyelids are placed with a few decisive touches; the mustache is swept in directional marks that describe growth and shine without counting hairs. The collar is summarized rather than embroidered; its crispness is an effect of value and placement, not meticulous drawing. The cloak is stated broadly, then adjusted with a handful of cooler glints and warmer shadows that suggest folds without narrating them. Velázquez’s brush never shows off. It simply arrives at the necessity of each passage, which is why the image feels so inevitable.

The Ethics of Self-Representation

Self-portraits tempt artists to perform identity—hero, martyr, virtuoso. Velázquez declines the audition. He appears neither at the easel nor in the act of painting; he wears no chain of office, no emblems of favor. The likeness asserts dignity through poise, not props. This refusal of theatrics amounts to an ethics: the same fairness he grants to monarchs and dwarfs he grants to himself. The underlying claim is that a person’s presence, truthfully seen, is enough. In an age of allegorical self-fashioning, that modesty is radical.

Dialogue with Italian Painting

Italian art informs the portrait without overwhelming it. From the Venetians he learned how to build flesh with air between the strokes; from Rome he absorbed a sculptural sense of head and neck. But where a Titian self-portrait might swim in sumptuous color and a Caravaggio head might contract into drama, Velázquez opts for equilibrium. The Roman lessons polish his structure; the Venetian lessons soften his edges; the Spanish temperament governs both. The synthesis is cosmopolitan yet unmistakably his.

Comparison with Court Portraits

Placing this self-portrait alongside early likenesses of Philip IV, the Count-Duke of Olivares, or the Infanta reveals a shared grammar: a plain ground, a disciplined palette, the eloquence of collar and face, and the belief that atmosphere outranks ornament. Yet the pitch changes. Court sitters project state; the painter projects craft. Kings borrow grandeur from the frame; the artist borrows none. The parity of treatment—applied to sovereign and self—confirms the portraitist’s inner scale. He measures people not by status but by the accuracy with which they occupy light.

The Chosen Instant

Velázquez freezes not a dramatic moment but a human interval. The head has just turned into the light; the lips rest between words; the eyes hold a steady evaluation. One can imagine the painter catching himself in a mirror or in the mind’s mirror after hours of painting other faces: not a vanity check, but a calibration. The chosen instant is the time of painting itself—quiet, sustained attention—translated into image.

Surface, Ground, and the Sense of Air

The thinness of the paint film in the ground lets the weave of the support whisper through, which makes the surrounding air granular and plausible. The thicker, more fused paint of the face feels denser, as if the head gathered matter from the room. That difference in density is not merely technical; it is poetic. It enacts the emergence of presence from atmosphere—the core miracle of portraiture—without trumpets.

Material Truth and Tactile Illusion

Velázquez converts small value shifts into tactile facts. The beard reads as hair because a few strokes catch the particular way light snags on bristles. The collar looks cool and slightly stiff because its highlights are high-key but never pure white, and because he grades the fall of light across the curve with sparing attention. The skin looks alive because warm and cool notes are mixed without formula, and because the transitions are broad enough to keep the surface breathing. The hand never competes with the head for resolution; this too is a moral choice.

The Gaze and Its Address

Whom does Velázquez look at? The eyes are oriented slightly off center, which prevents confrontation and also avoids the vanity of performance. The gaze is investigative, the sort one turns upon a subject to understand how light binds its parts. That attitude of looking outward is what gives his portraits their uncanny presence: the sitter seems to be participating in the same act of seeing as the painter. In the self-portrait, that loop closes upon itself. We witness a mind inspecting its own visibility.

Time and the Life in Paint

Because the surfaces are not overworked, time remains legible in the image. You can sense the speed of the collar, the slower calibration of the eyes, the final consolidating passes that settle the silhouette. That layered temporality keeps the picture alive. It feels as if the painter could return to it at any moment, make a single adjustment, and withdraw again. Few self-portraits achieve this balance between completion and possibility.

Viewer Experience

From across a room, three chords dominate: the pale oval of the face, the cool collar beneath it, and the dark garment below. Step closer and those chords dissolve into measured variations—the blush at the cheek, the precise notch of the philtrum, the flicker of light on the mustache’s curl, the softened break between jaw and neck. Closer still, the brush declares its decisions. The pleasure of the picture lies in this oscillation: it yields both person and workmanship, never sacrificing one to the other.

Legacy and Influence

The self-portrait helped fix the image of Velázquez in the European imagination: sober, brilliant, and allergic to display. Later painters—Goya, Manet, Sargent—took cues from this equilibrium. They learned that authority can arise from restraint, that backgrounds can be air rather than drapery, that a collar or cuff can carry structure, and that psychological depth grows from accuracy, not from exaggeration. The portrait also speaks to contemporary viewers used to photographic exactness: its truth is not a matter of micro-detail but of relations—light to form, edge to air, gaze to viewer.

What the Picture Says About Painting

Beyond likeness, the canvas proposes a philosophy. Painting, it says, is an ethics of attention. It honors the world by seeing it well, whether the subject is a king, a water seller, or the painter himself. It trusts a few essentials—light, value, edge—to do the noble work that ornament promises and rarely delivers. It depends on judgment rather than on tricks. And it believes that dignity is not bestowed by props but revealed by presence.

Conclusion

In “Self-Portrait,” Velázquez offers a compact creed. He stands in air, turns into light, and allows the viewer a measured approach. Nothing begs for admiration, yet everything earns it. The hair’s buoyant edges, the collar’s cool architecture, the face held at the pitch of serious regard—together they establish the painter not as a celebrity of the studio but as a craftsman of truth. The portrait becomes a meeting in which the artist introduces himself in the language he trusts most: a grammar of light and silence.