Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Murillo’s “Self-portrait”

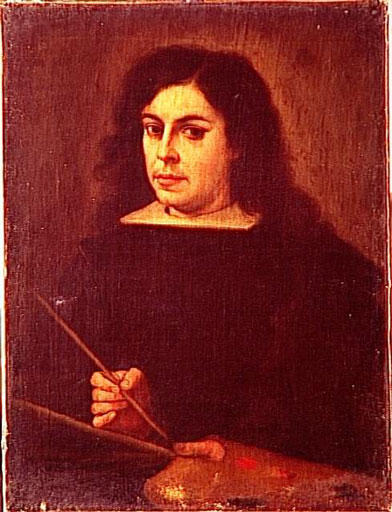

“Self-portrait” by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo offers a rare and intriguing glimpse into the inner world of one of Spain’s most beloved Baroque painters. Unlike his luminous scenes of the Virgin and Child, saints, and Sevillian street children, this canvas turns the artist’s gaze back upon himself. The result is an image that is at once restrained and revealing, modest and quietly assertive.

The painting shows Murillo from the waist up, seated or standing behind a painter’s palette. He holds a long brush in his right hand, while his left hand steadies the palette resting at the bottom edge of the canvas. His dark clothing blends into the warm brown background, making his pale face and white collar the primary focus. The expression is calm, intelligent, and slightly reserved, as if he is aware of being observed yet determined to maintain control of his image.

This work belongs to the long tradition of self-portraiture in European art, where artists fashioned their own public identity on canvas. For Murillo, whose reputation in Seville was immense, a self-portrait was not merely a personal exercise but a statement about the dignity and seriousness of the painter’s profession.

Historical Context and the Status of the Artist

In seventeenth century Spain, painters occupied an ambiguous social position. On the one hand, they created works for churches, aristocrats, and religious orders, and their art played a central role in the visual culture of the Counter Reformation. On the other hand, they were often considered craftsmen rather than intellectuals, grouped with artisans rather than with poets or scholars.

Artists like Velázquez in Madrid and Murillo in Seville worked hard to elevate their profession. Velázquez painted himself prominently in Las Meninas as a courtier and gentleman. Murillo, though less overtly ambitious in his imagery, also presented himself with a sober dignity that claims respect.

In this self-portrait, Murillo does not pose in a luxurious studio or surround himself with symbolic attributes of learning. Instead, he chooses a simple, almost austere setting. The background is a flat, warm tone that suggests a studio wall but contains no decorative details. This simplicity directs attention to the face and hands, the instruments of artistic creation. The palette and brush identify him clearly as a painter, while the thoughtful gaze and composed expression hint at the intellectual and imaginative labor behind his works.

By portraying himself in this way, Murillo asserts that painting is not merely manual work. It is a discipline that combines craft with thought, and he, as its practitioner, deserves to be seen as a serious and reflective figure.

Composition and Framing

The composition of the self-portrait is carefully structured to create balance and focus. Murillo positions himself slightly off center to the right. His torso forms a dark triangular mass that anchors the lower half of the canvas. From this base, the vertical of his neck and head rises toward the upper center.

The palette appears near the bottom edge, angled diagonally from left to right. Its curved outline and the faint touches of color on its surface introduce a gentle arc that contrasts with the more rigid vertical and horizontal lines of the figure. The long brush in his hand extends along another diagonal, leading the viewer’s eye toward his face. Through these lines, Murillo subtly guides our attention from the tools of his trade to the person who wields them.

His left hand grips the palette near the bottom of the painting, while his right hand, holding the brush, is placed higher and closer to the center. This arrangement gives a sense of movement and readiness. He appears to be on the verge of making a stroke, as if we have caught him in the act of painting either himself or another work.

The background remains intentionally neutral. Its warm brown tones echo the shadows of his clothing, ensuring that the lighter areas of the painting stand out. There is no architectural frame painted around him, no window or elaborate curtain. The simplicity of the setting reinforces the introspective nature of the portrait.

Light, Color, and Atmosphere

Murillo’s use of light in this self-portrait is restrained but effective. A soft illumination falls from the left, touching his forehead, nose, and cheeks, as well as the white collar at his neck and the knuckles of his hands. These lit areas emerge from the deeper shadows of his dark clothing and the background, creating a subtle yet perceptible contrast.

The color palette is dominated by warm browns, deep blacks, and muted reds, with only a few touches of brighter pigment on the palette itself. The overall tonality is earthy, reflecting the seriousness of the subject matter. The white collar serves as a visual anchor, providing a crisp accent that sets off the face and reinforces the vertical axis of the composition.

Unlike many of his religious paintings, where Murillo bathes figures in golden light and pastel hues, here he chooses a more serious, subdued atmosphere. This tonal restraint aligns the self-portrait with the sober tradition of Spanish portraiture, where dark clothing and neutral backgrounds often dominate, allowing the psychological presence of the sitter to take precedence.

The brushwork is relatively smooth in the face, with subtle transitions of value modeling the cheeks, eyelids, and lips. In the background and clothing, the paint appears looser and more textural, giving a sense of depth without distracting from the central features. This contrast in handling reinforces the hierarchy of attention: personality first, environment second.

The Face of the Artist

The most compelling element of the painting is Murillo’s face. He presents himself as a man in the maturity of his career, neither youthful nor aged. His dark hair falls to his shoulders in loose waves, framing his oval face. The eyebrows are softly arched, the nose straight, the mouth somewhat full and closed in a neutral expression.

The eyes, slightly asymmetrical as they so often are in life, gaze outward toward the viewer. There is a steady, thoughtful quality to this gaze. It is neither confrontational nor submissive. Instead, it communicates a quiet confidence and a touch of introspection. Murillo seems aware that his image will be examined by others, yet he does not overplay emotion.

This calm demeanor may reflect the way Murillo wished to be remembered: as a composed, serious professional, devoted to his work and aware of his own accomplishments but not arrogant. Unlike some self-portraits that flaunt virtuosity or theatrical flair, this image communicates a sense of modesty.

At the same time, there is a hint of melancholy in the downward tilt of the mouth and the softness of the eyes. This nuance suggests an awareness of the passing of time, of the challenges and responsibilities that accompany artistic success. The self-portrait thus becomes not only an advertisement of skill but a contemplative statement about the artist’s own humanity.

Hands, Palette, and Brush as Symbols

Murillo gives particular attention to his hands, the most active elements of the portrait after the face. His right hand grips the lengthy brush with practiced ease, fingers gently curved. The left hand steadies the palette in a more relaxed pose.

These hands speak of the labor and discipline of painting. They are not idealized; veins and knuckles are visible, indicating real physical work. The palette itself bears dabs of color, though in the reproduction they appear muted. The presence of these pigments reminds viewers that the entire world of Murillo’s paintings, from radiant Madonnas to lively children, stems from such simple materials arranged by these very hands.

The long brush creates a visual bridge between the palette and the face. Symbolically, it can be seen as a link between matter and spirit, between pigment and vision. The palette holds the raw color, the brush transforms it, and the mind directs the transformation. By placing himself literally between these tools, Murillo asserts his role as mediator, the one who turns inert materials into living images.

Identity, Reputation, and the Self-portrait Tradition

Self-portraits have always served multiple purposes. They can be private exercises in self-examination, public statements of identity, or demonstrations of skill. In Murillo’s case, all three functions appear to be at work.

By painting himself, Murillo participates in a distinguished lineage that includes Dürer, Rembrandt, Velázquez, and many others. These artists used self-portraiture to explore their evolving identities and to present themselves to patrons and posterity. Murillo’s version, though less dramatic than some, shares the same fundamental impulse: to leave a trace of the person behind the artworks.

Given his prominence in Seville as the leading painter of his time, this self-portrait would also have carried a promotional dimension. It shows the face that stood behind famous altarpieces and devotional canvases, giving patrons a tangible image of the artist they admired. At the same time, it is devoid of overt luxury or self-aggrandizement. Murillo wears simple dark clothing rather than silk or armor. He appears as a working artist, not as a nobleman.

This choice reflects both Christian humility and the ethos of the Franciscan-influenced culture of Seville, where simplicity and charity were highly valued. Yet within that humility, Murillo quietly affirms his stature: he faces the viewer directly, brush in hand, as someone who knows his worth without needing to trumpet it.

Psychological Insight and Intimacy

One of the striking aspects of this painting is the sense of intimacy it creates. The viewer stands very close to Murillo, at roughly eye level. The absence of elaborate surroundings makes the interaction feel direct and personal, as if we have entered the artist’s studio during a quiet moment.

The subdued lighting and warm tones further enhance this intimacy. There is no harsh spotlight or theatrical contrast. Instead, a gentle glow reveals the features of the face, inviting contemplation rather than shock.

Murillo’s expression suggests self-awareness. He seems to be considering not only what he sees in the mirror but also how he wishes to appear to others. The slight turn of the head and the calm gaze imply that he accepts this dual role of observer and observed. In this sense, the painting gives us a subtle glimpse into the psychological complexity of self-portraiture, where the artist must be both subject and creator.

Comparison with Murillo’s Other Works

When placed alongside Murillo’s religious and genre paintings, the self-portrait reveals both continuity and contrast. In his depictions of saints, the Virgin, and Christ, Murillo often emphasized tenderness, spiritual light, and emotional immediacy. His street children, by contrast, display lively movement and playful energy.

In this self-portrait, many of those qualities are toned down but not absent. The soft modeling of the face and the warm palette echo the gentle atmospheres of his devotional works. There is a quiet compassion in his own eyes that mirrors the way he painted the eyes of his subjects. The simplicity of the background recalls the minimal settings of some of his single-figure saints, where the person emerges from darkness as a focal point for meditation.

At the same time, the self-portrait lacks overt religious symbolism or narrative drama. It belongs to the realm of everyday reality. This difference highlights Murillo’s versatility. He could move from the mystical to the mundane while maintaining a coherent style rooted in human warmth and subtle light.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Today, Murillo’s “Self-portrait” holds interest not only for admirers of Baroque art but also for those fascinated by the human dimension of artistic creation. In an era saturated with images and self-representation, the painting offers a quieter, more reflective model of how an artist might present himself.

There is no theatrical costume, no exaggerated pose. Instead, we see a man who looks directly at us, tools in hand, ready to work. The portrait reminds us that behind every celebrated artwork stands an individual who spent long hours confronting a blank surface, wrestling with ideas, and making countless decisions about line, color, and form.

For historians, the self-portrait contributes to our understanding of Murillo’s personality and self-image. For general viewers, it humanizes a figure often known only through his religious canvases. It invites us to consider the artist not as a remote genius but as a person who recorded his own features with honesty and restraint.

Conclusion

“Self-portrait” by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo is a compact yet profound statement of artistic identity. Through a restrained composition, subtle light, and a calm, introspective expression, Murillo presents himself as a serious, thoughtful painter whose craft is both manual and intellectual.

The dark clothing, simple background, and focus on hands and face underline the dignity of the working artist. The palette and brush become symbols of creative power, while the warm tones and soft modeling link the self-portrait to the emotional depth found in his religious and genre scenes.

Ultimately, this painting offers more than a likeness. It is a visual meditation on what it means to be an artist: to observe, to create, to understand oneself, and to shape how future generations will remember one’s presence. In facing his own reflection and translating it into paint, Murillo invites us into that reflective space, encouraging us to see not only his features but the quiet strength and sensitivity that fueled his remarkable body of work.