Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

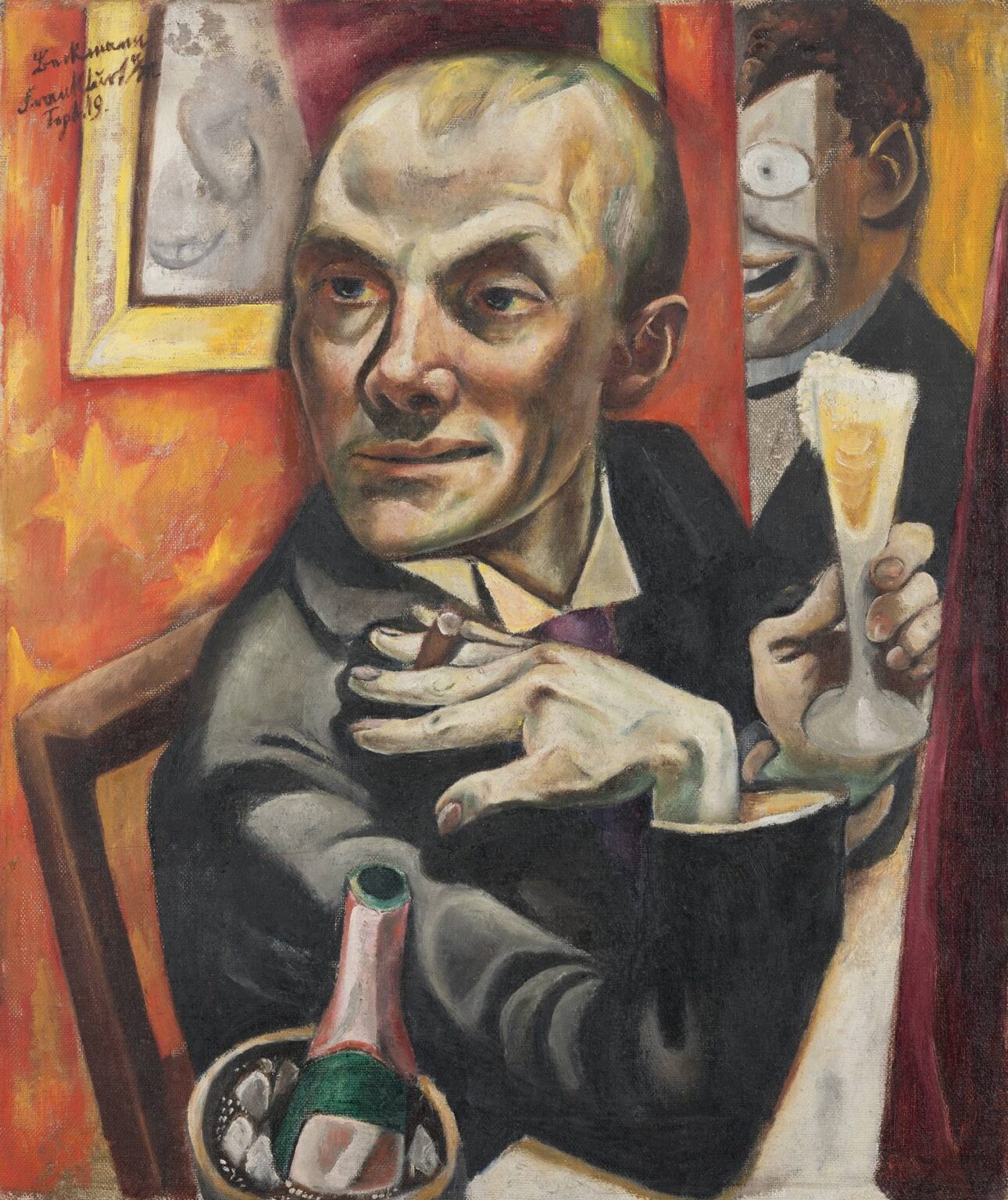

Max Beckmann’s Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass (1919) stands as a vivid testament to the artist’s emergence from the shadows of World War I into the electrifying cultural ferment of Weimar Berlin. In this painting, Beckmann positions himself at the threshold of a café or cabaret, caught in a moment of ambiguous celebration. The half‑finished champagne glass, the stub of a cigarette poised between his fingers, and the masked figure peering in from the right combine to create a dynamic tableau that is as much about psychological tension as it is about social spectacle. Rendered in oil on canvas, the painting showcases Beckmann’s mastery of form, color, and composition at a pivotal moment in his career. Over the course of this analysis, we will explore the historical backdrop of postwar Germany, Beckmann’s stylistic evolution, the painting’s compositional framework, chromatic strategies, symbolic motifs, and the work’s enduring resonance in both the artist’s oeuvre and the broader narrative of twentieth‑century art.

Historical Context: Weimar Berlin in 1919

The year 1919 marked a watershed in German history. The abdication of the Kaiser and the end of imperial rule gave way to the Weimar Republic, a fragile democracy born amid economic collapse, political revolution, and social upheaval. Berlin, in particular, became a hotbed of avant‑garde experimentation, where cabarets, cafés, and theaters served as crucibles for new artistic, political, and sexual freedoms. Yet beneath the veneer of bohemian revelry lay traces of collective trauma: veterans struggling with shell shock, families decimated by the influenza pandemic, and citizens grappling with food shortages and hyperinflation. Beckmann, having served in a medical unit near the front lines, returned profoundly altered by the brutality and absurdity of war. Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass emerges against this fraught backdrop, encapsulating both the exhilaration and the anxiety of a society attempting to celebrate life while reeling from unprecedented devastation.

Beckmann’s Postwar Transformation

Prior to the war, Beckmann’s work reflected the influence of Jugendstil’s decorative elegance and the lingering echoes of Impressionism. However, his wartime experiences catalyzed a radical shift toward a more introspective and emotionally raw approach. He abandoned idyllic landscapes and decorative motifs in favor of portraits and scenes that grappled with modern alienation, existential vulnerability, and the paradox of human resilience. By 1919, Beckmann had begun to develop his signature style: bold outlines, flattened spaces, and color used not merely to imitate reality but to convey psychic states. The Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass reflects this transformation, intertwining his disciplined draftsmanship with a newfound urgency and symbolic density. In this painting, Beckmann is both subject and commentator, a man who raises a glass to the future even as he scans the shadows for hidden threats.

Formal Composition and Spatial Structure

Beckmann organizes the painting around a dynamic interplay of diagonal and vertical axes. The central diagonal runs from the lower left—where a champagne bucket and bottle rest—to the upper right, where the masked figure enters. This diagonal is mirrored by the artist’s arm extending toward the champagne glass, creating a sense of forward momentum. Counterbalancing these slanted lines are the verticals of the chair back, the doorway, and the artist’s torso, which lend stability to the composition. The tabletop’s horizontal edge provides a grounding element, segmenting the space into fore-, middle-, and background planes. Beckmann deliberately flattens spatial depth: the background walls, though richly textured, recede only modestly, forcing viewer and subject into an immediate, almost confrontational proximity. This compression enhances the painting’s theatrical quality, as though the scene unfolds on a confined stage where every gesture and glance carries amplified meaning.

Color and Light: Conveying Mood through Hue

The chromatic scheme of Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass is striking in its contrasts. The background’s vibrant reds and oranges—applied in loose, pulsating strokes—evoke the warmth of interior lamps, the glow of stage lights, or perhaps the embers of a rebuilding nation. These fiery tones set off the cooler grays and muted greens of Beckmann’s jacket and the gray‑green wash of the tablecloth. His face and hands, rendered with layers of pinks, peaches, and subtle greens, emerge as luminous focal points against the darker clothing. The champagne glass, filled with pale effervescence, captures light in a way that suggests fleeting joy, while the bottle’s pink label and green foil offer a modern counterpoint to the draped curtains. Beckmann’s orchestration of warm and cool contrasts, punctuated by glints of white and yellow, conveys both the allure of the moment and the underlying tension of a world in flux.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Beckmann’s technique in this painting demonstrates a confident balance between painterly texture and controlled articulation. The background walls are built from layered, energetic strokes—some vertical, some horizontal—creating a rhythmic tapestry of color that hums with energy. In contrast, the rendering of the champagne glass and bottle employs smoother, more refined strokes to suggest translucency and form. The face and hands benefit from a nuanced approach: glazes of flesh tone are layered to model volume, while short, directional strokes impart a subtle vibration of life. The suit’s folds and the chair’s carved wood converge in thicker impasto, giving these objects a tactile weight. Across the canvas, Beckmann’s varied brushwork binds the elements together into a cohesive whole, making the surface itself a record of the artist’s emotional engagement.

Symbolic Motifs: Champagne, Cigarette, and Mask

Three central motifs—the champagne glass, the cigarette, and the masked figure—anchor the painting’s symbolic register. Champagne, long associated with celebration and luxury, here becomes an emblem of precarious optimism: Beckmann holds it aloft as if to toast the future, yet its barely half‑filled state hints at scarcity and compromise. The cigaret, pinched between his forefinger and middle finger, conveys both self‑sedation and social ritual, as if the artist relies on nicotine to stave off anxiety or to maintain composure. The masked figure lurking in the doorway, its grin unnervingly wide and mechanical, suggests the specter of carnival‑style anonymity or the hidden faces lurking behind social facades. This intruder may represent the forces—political agitators, profiteers, disenchanted masses—that threaten to invade quiet moments of personal revelry.

Psychological Tension and Self‑Reflection

Beyond the literal props, Beckmann’s Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass operates as a meditation on the artist’s inner state. His sideways glance is the painting’s most revealing feature: rather than confront the viewer directly, he looks off‑stage, as though vigilant for unexpected intruders or second thoughts. This gesture conveys ambivalence—an openness to celebration tempered by the wary anticipation of upheaval. The tilt of his head and the tension in his eyebrows suggest that the toast is both genuine and guarded. The painting thus doubles as a self‑interrogation: Beckmann acknowledges his desire to embrace life’s pleasures, while refusing to ignore the chaos that lurks just beyond the café’s warm glow.

Connection to Weimar Culture and Cabaret Scene

In 1919, Berlin’s cabarets and cafés served as epicenters of cultural renewal, offering spaces where artists, writers, and intellectuals gathered to test new ideas. Afternoon meetings over coffee gave way to evening revelry accompanied by jazz, satirical performances, and acerbic commentary on the republic’s failures. Beckmann’s painting situates itself within this milieu: the red drapery and framed sketches in the background evoke café interiors, while the masked visitor suggests a performative act—perhaps a comedian or puppeteer stepping onto the stage. Yet the scene avoids romanticizing cabaret life; instead, it captures the dual nature of these venues as sites of liberation and zones of uneasy satire. Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass thus becomes a microcosm of Weimar culture itself: intoxicating, subversive, and always on the edge of disintegration.

Relation to Beckmann’s Oeuvre and Later Works

Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass occupies a crucial position within Beckmann’s broader trajectory. Having abandoned pastoral and decorative themes, he turned to self‑portraiture as a way to probe personal and social crises. The painting’s tight framing and symbolic density anticipate the confrontational compositions of his Gesichter etchings (1915–1918) and the allegorical largescale canvases he would create in the 1920s and 1930s, such as Actors (1924) and The Night (1918–1919). Its cabaret setting prefigures his interest in theater and performance as metaphors for human roles and masks. Moreover, the work’s oscillation between realism and distortion—in the face’s modeling versus the caricature’s hyperbole—signals the tension that would inform his Expressionist‑influenced paintings in the years leading up to his exile.

Artistic Legacy and Influence

Beckmann’s Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass resonated with contemporaries who saw in it a powerful embodiment of postwar ambivalence. Its influence extended to artists grappling with modernity’s contradictions—figures like Otto Dix and George Grosz, who explored the grotesque and the satirical within Weimar society. In subsequent decades, the painting has been studied as an exemplar of self‑portraiture that balances personal confession with social critique. Its insistence on the artist as both participant and observer paved the way for later modernists—Franz Kline, Elaine de Kooning, and Francis Bacon—who similarly used self‑portraiture and performance motifs to navigate the pressures of their historical moments.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Self‑Portrait with Champagne Glass (1919) transcends its immediate subject—a man raising a glass in a café—to become a searing allegory of postwar identity, social rupture, and the precarious pursuit of joy. Through dynamic composition, contrasting color schemes, textured brushwork, and potent symbolism, Beckmann captures the tension between revelry and vigilance, pleasure and anxiety. The masked figure, the half‑empty glass, and the poised cigaret converge to depict a society—and an artist—caught between the promise of renewal and the specter of collapse. As both a document of Weimar Berlin’s cabaret culture and a cornerstone of Beckmann’s artistic evolution, the painting endures as a powerful reminder of art’s capacity to confront history’s most unsettling moments with unflinching honesty.