Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

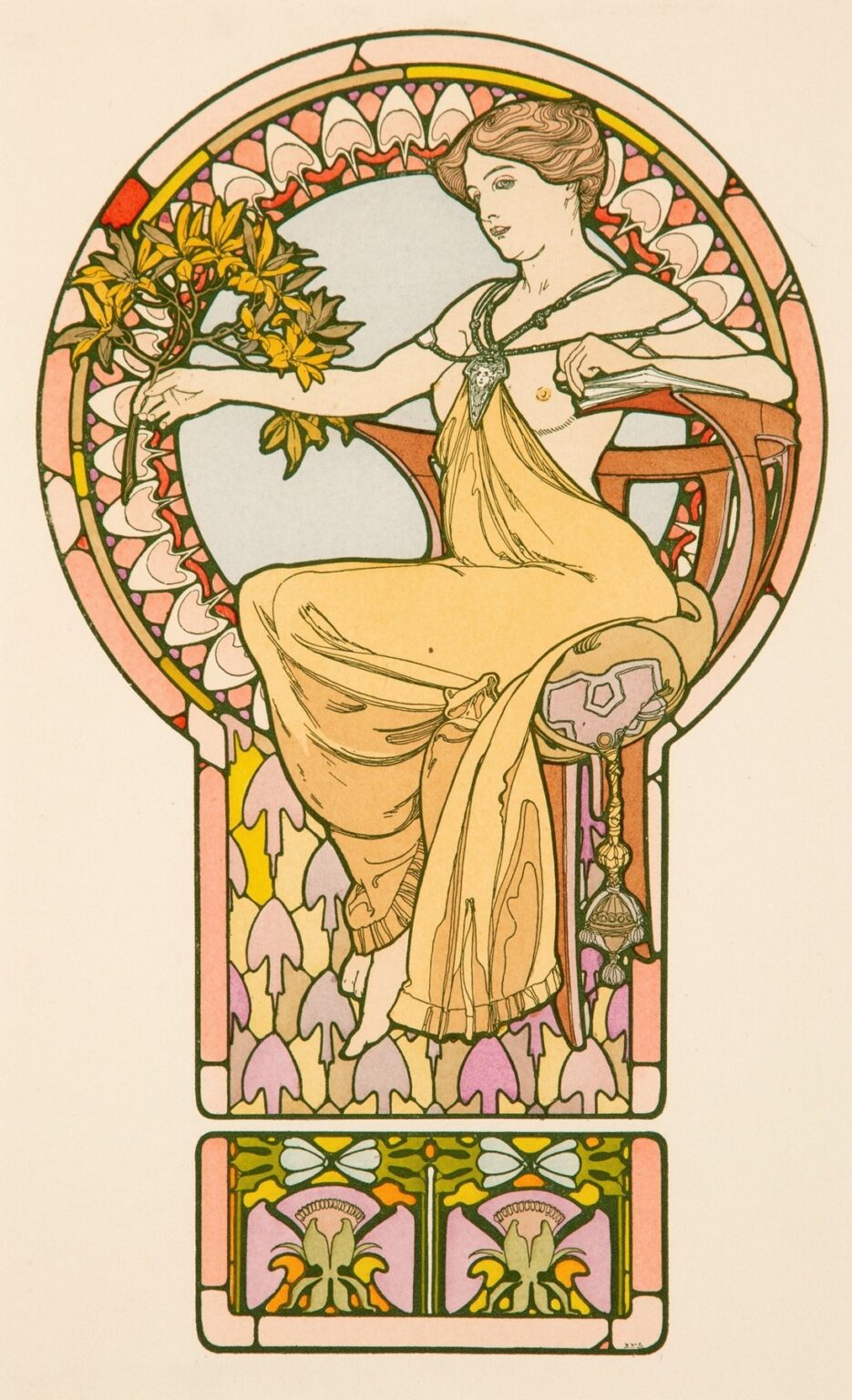

“Seated Woman, plate no. 48 from Documents Décoratifs” by Alphonse Mucha exemplifies the synthesis of fine art and applied decoration that came to define Art Nouveau at the turn of the 20th century. Created in 1901 as part of the influential publication Documents Décoratifs, this lithographic plate presents a serene female figure framed by intricate geometric and botanical motifs. Unlike Mucha’s theatrical posters, this image was intended for designers and artisans seeking fresh vocabulary for interior decoration, textiles, and graphic arts. The woman’s relaxed posture, elegant drapery, and the ornamental structure surrounding her invite contemplation of both individual beauty and the decorative possibilities that flow from natural forms. Through this work, Mucha articulates a vision of ornament as living art, demonstrating how a single image can inspire architecture, furniture, metalwork, and countless other crafts.

Historical and Cultural Context

The early years of the 20th century witnessed a flourishing of decorative arts movements across Europe. In France, Documents Décoratifs served as a seminal showcase for innovative patterns, motifs, and compositions that designers could adapt to various media. Alphonse Mucha, already celebrated for his colorful posters and commercial illustrations, contributed a series of plates that distilled his signature style—fluid linework, stylized botanical forms, and harmonious palette—into modular elements for practical use. His participation in Documents Décoratifs reflects the era’s desire to democratize beauty, bringing artistic excellence beyond gallery walls and into everyday objects. At a moment when industrial production threatened to standardize design, Mucha and his contemporaries championed handcrafted elegance and organic inspiration as antidotes to mechanical uniformity.

Publication in Documents Décoratifs

Documents Décoratifs, founded by architect and designer Eugène Grasset and editor E. de Mirbel, aimed to provide craftsmen and manufacturers with a steady stream of new ideas. Plate no. 48, “Seated Woman,” appeared amid a broader survey of ornamental experiments. Unlike wallpaper repeats or textile swatches, Mucha’s contribution offered a central figural motif surrounded by decorative patterns that could be extracted or reinterpreted. The plate’s circular framing device and rectangular base panel suggest applications in stained glass, mosaic, or inlay work. Interior decorators might echo the circular halo in ceiling medallions, while furniture makers could carve the geometric panels into chair backs or cabinet doors. Through Documents Décoratifs, Mucha’s art transcended its original form, seeding countless variations across European design studios.

Composition and Spatial Organization

“Seated Woman” unfolds through a carefully calibrated composition that balances figure and ornament. The design divides vertically into two zones. The upper, circular section cradles the figure in a decorative halo of repeated petal shapes and subtle color shifts. This circular motif draws the eye inward to the woman’s poised form. Below, a rectangular panel of stylized tulip-like forms and a band of geometric flourishes provide visual weight and grounding. Mucha’s choice to extend the figure’s flowing robe into the base unifies both zones, creating an uninterrupted descent of line from head to hem. Negative space around the circle and rectangle adds breathability, preventing the composition from feeling overcrowded and allowing artisans to imagine the plate in varied dimensions.

Mastery of Line and Contour

Central to Mucha’s aesthetic in “Seated Woman” is his unparalleled command of line. The contours of the figure’s drapery, hair, and limbs trace a continuous, rhythmic path that guides the viewer’s gaze organically through the plate. The garments wrap around her form in elegant, calligraphic sweeps, their edges varying in thickness to suggest folds and volume without heavy shading. The hair, arranged in soft coils, reveals the same sensitivity to line weight, with subtle undulations that evoke both strength and delicacy. Surrounding the figure, the ornamental border lines echo her curves, establishing visual harmony between the human and decorative elements. Mucha’s line work thus accomplishes two feats: it defines the sitter with sculptural precision while weaving her into the broader tapestry of ornament.

Color Palette and Printing Technique

Mucha’s color choices for this decorative plate reflect both his poetic sensibility and the technical demands of lithography. The seated woman’s drapery glows in warm ochre and soft apricot, while her skin remains a gentle ivory that contrasts with the saturated halo behind her. The circular frame alternates pale pink and soft yellow leaf motifs against a neutral ground, suggesting stained glass or enameled metal. The base panel’s lavender and chartreuse forms further diversify the palette, providing a lively counterpoint to the figure’s warmth. Achieving such harmonious yet varied hues required careful planning of color separations across multiple stones. Mucha collaborated with lithographers skilled in precise registration, ensuring that transparent inks overlapped seamlessly to create subtle gradients and preserve the crispness of his characteristic linework.

Symbolic Elements and Iconography

While “Seated Woman” serves primarily as a decorative exemplar, its iconography bears symbolic resonances. The circular halo behind the figure’s shoulders evokes both a rising sun and a sacred mandorla, suggesting themes of renewal and inner illumination. The floral branch she holds—its yellow blossoms rendered with botanical fidelity—may allude to spring’s awakening or the life-giving force of nature. The stylized tulip motifs in the base panel, repeated with rhythmic precision, symbolize devotion and elegance in the language of flowers. By embedding these motifs within a decorative schema, Mucha invites observers to perceive deeper layers of meaning: ornament becomes allegory, and the plate transforms from mere pattern to a meditative composition celebrating the relationship between humanity and the natural world.

The Feminine Ideal and Psychological Presence

Mucha’s depiction of the female figure transcends simple portraiture; it embodies an Art Nouveau ideal of graceful calm and gentle introspection. The woman’s seated posture—one arm extended to present the floral sprig, the other resting lightly on a curving armrest—communicates both openness and repose. Her downcast gaze and serene expression suggest inner contemplation rather than dramatic flair. Mucha elongates her limbs and drapery to emphasize a rhythmic flow, aligning her form with the ornamental lines that envelop her. Although she remains an archetype rather than an individualized portrait, the subtle nuance of her features—a slight tilt of the head, the softness of her jawline—imbues her with psychological presence. She becomes a universal muse for designers, a feminine emblem whose beauty resonates across contexts.

Ornamental Patterns and Decorative Vocabulary

Surrounding the central figure, Mucha assembles a sophisticated vocabulary of ornamental forms drawn from diverse sources. The circular frame’s alternating leaf shapes recall Byzantine mosaic tesserae and medieval illumination, while the base panel’s repetitive tulip forms echo Ottoman textile patterns. Between these, interstitial bands of abstract flourishes and small squares suggest Celtic interlace or early Gothic tracery. Together, these disparate inspirations cohere into a distinctive Art Nouveau lexicon characterized by sinuous curves, botanical stylization, and geometric symmetry. Designers consulting this plate in Documents Décoratifs could isolate individual motifs for surface decoration or adapt entire sections to larger architectural schemes. Through “Seated Woman,” Mucha codifies a modular set of elements that could generate boundless decorative permutations.

Integration of Figure and Background

One of the most remarkable features of this plate is the seamless integration of human form and ornamental structure. The woman does not merely sit against a backdrop; she appears to emerge from the halo and panels themselves. Her drapery flows into the tulip patterns below, while the circular frame seems to cradle her like a throne. There is no hard separation between figure and ornament; instead, each informs the other. Mucha achieves this through consistent line quality and by echoing curves across both domains. The result is an immersive whole—an image designed not for passive viewing but for active adaptation by decorators seeking a unified vision of art and environment.

Influence of Japonisme and Other Artistic Currents

Mucha’s decorative plates synthesize multiple artistic influences that were in vogue at the fin de siècle. Japonisme, with its emphasis on flat color areas and strong outlines, manifests in the plate’s minimal modeling and bold contour lines. At the same time, medieval manuscript illumination informs the treatment of foliage and the medallion-like halo, while classical sculpture resonates in the poise of the seated figure. The geometric precision of the base panel echoes the precision of Moorish tilework and Byzantine icon framing. By weaving these elements into a coherent style, Mucha created a visual lexicon that both celebrated the decorative arts’ eclectic sources and propelled them forward into a new design era.

Technical Process and Materials

“Seated Woman” was reproduced via multi-stone lithography, a printmaking process wherein each color requires a separate limestone plate. Mucha began with detailed line drawings, which were transferred onto stones by skilled craftsmen. He then created color keys to specify ink mixtures for each area—transparent washes for the drapery, opaque blocks for the halo, and stippled gradients for background fields. Precise registration marks ensured alignment across impressions, and careful proofing allowed for minor adjustments before final printing. The resulting prints boast the clarity of original drawings combined with the subtle richness of layered color. For artisans working in textiles or ceramics, lithographic prints like this served as master templates, guiding color separations and motif placements in other media.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its release in Documents Décoratifs, “Seated Woman” garnered immediate attention from architects, textile designers, and furniture makers eager to incorporate Art Nouveau motifs. The plate’s balanced synthesis of figure and ornament proved especially popular for interior schemes, where carpets, stained glass, and friezes echoed Mucha’s patterns. Over the decades, the plate influenced Art Deco stylizations and later mid-century modern abstractions, where designers distilled its sinuous lines into more streamlined forms. Today, collectors prize original impressions for their technical excellence and historical significance. Art schools continue to study Mucha’s decorative vocabulary, and digital platforms have made his plates accessible worldwide, inspiring contemporary designers to reinterpret his harmonious marriage of beauty and utility.

Conclusion

“Seated Woman, plate no. 48 from Documents Décoratifs” stands as a testament to Alphonse Mucha’s conviction that decoration and fine art need not occupy separate realms. With fluid linework, a nuanced color palette, and an inventive assembly of ornamental motifs, Mucha crafted a plate that transcends its original publication context to become a perennial source of inspiration. The serene figure, framed by a radiant halo and grounded by rhythmic floral panels, embodies the Art Nouveau ideal of art integrated into everyday life. More than a static image, this plate serves as a living blueprint, inviting each generation of designers and artisans to draw from its harmonious forms and breathe new life into its graceful vision.