Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

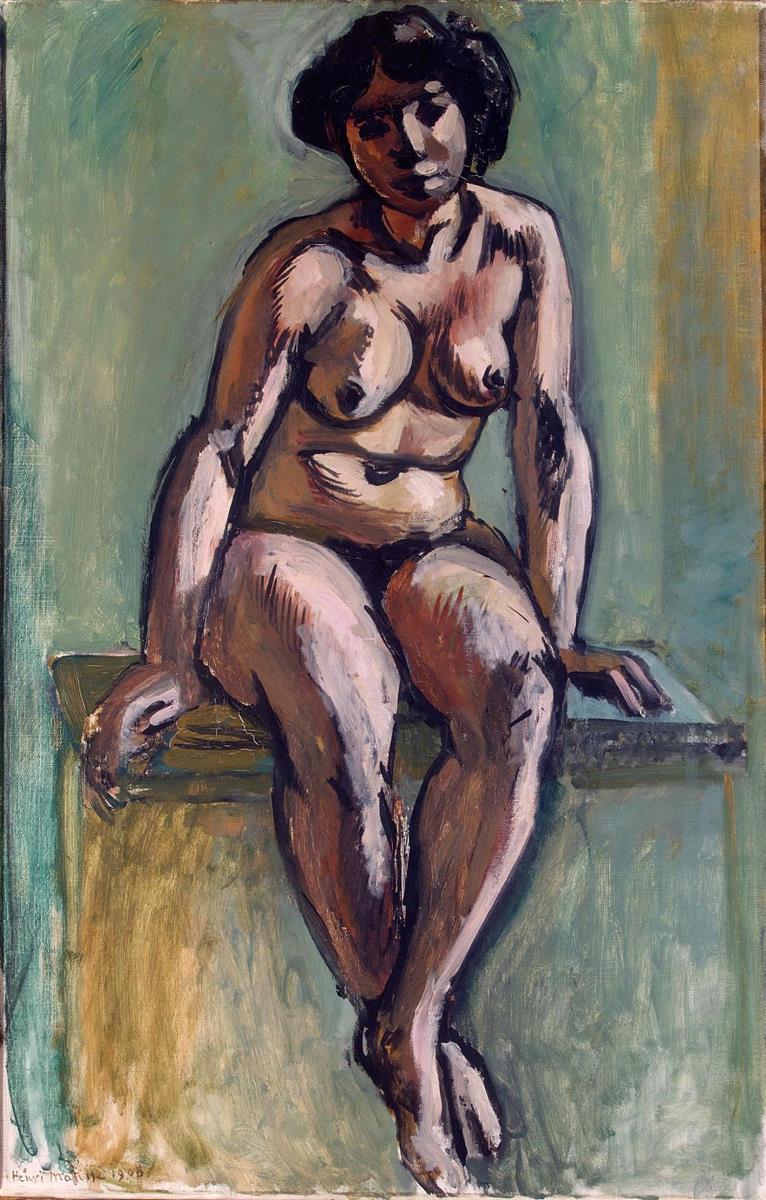

Henri Matisse’s Seated Woman (1908) captures a nude poised on the narrow ledge of a bench, suspended between stillness and slight sway. The figure occupies a tall, narrow field of cool green and ocher, her body built from purposeful slabs of warm color and ringed by assertive black contour. The head tilts with a calm, mask-like reserve; the hands brace behind the hips; the feet dangle toward the lower edge, emphasizing gravity and the body’s real weight. What looks at first like a straightforward studio exercise quickly reveals itself as a compact statement of Matisse’s 1908 ambitions: to unite the freedom of Fauvist color with an increasingly sculptural sense of structure, and to build human presence from a few, well-tuned decisions of line, plane, and temperature.

Historical Context

By 1908 Matisse had already shocked Paris with the blazing chroma of Fauvism. He was now refining that energy into a steadier grammar—fewer hues, clearer shapes, more explicit construction. At the same time he was modeling and casting sculpture, paring the figure into volumes and profiles that would travel back into paint. Seated Woman sits at the center of this pivot. It does not abandon color, but it harnesses it to explain mass and balance rather than to dazzle. The result is a modern classicism: a nude without myth, posed in a room without narrative props, but endowed with dignity through contour, measured contrast, and the unembarrassed display of the painter’s hand.

Composition and Format

Matisse chooses a vertical canvas that echoes the human body. The bench’s horizontal lip cuts across the lower third, creating a stable stage and a clear opposition of axes: the body’s dominant verticals against the bench’s stripe. The figure is slightly off-center, leaning toward the viewer’s left, which keeps the composition from settling into symmetry. The dangling feet, near the bottom edge, close the rectangle with a soft diagonal; the left arm descends along the torso, while the right arm sweeps back to the bench, a pair of lines that firm up the silhouette and lock the body to its perch. Around these vectors Matisse leaves generous breathing space—a field of green to the left, a band of ocher to the right—so the eye can read the figure as an object in a room rather than as a cutout pasted to the surface.

Pose and Gesture

The seated pose is simple and exact. Hips forward, knees angled, hands planted on the ledge, the model carries her weight believably. The tilt of the head turns the neck into a gentle column; the torso slumps a fraction, setting up soft folds at the abdomen; the shoulders round with the slightest fatigue. Nothing is melodramatic. Matisse aims for the dignity of ordinary balance, the way a living body composes itself when asked to hold still. Because the head leans and the knees turn, the figure avoids rigidity; the pose becomes a spiral, a quiet torque that animates the rectangle.

Palette and Color Strategy

The palette is restrained yet potent. Flesh is built from ochers, rose, russet, and lilac grays; shadows are deepened with olive and cool brown; highlights arrive as chalky, pink-tinged strokes that stop just short of white. The environment stays cool: a sea-glass green field occupies most of the background, while a narrow ocher band at right returns warmth without competing with the body. This temperature plan makes the figure advance—warm to cool, dense to airy—without resorting to theatrical lighting. The few darkest accents (under the chin, between the thighs, along the bench) act as hinges that articulate joints and clarify depth.

Contour and Drawing

Black contour is the painting’s grammar. It rings the shoulders and thighs with confident sweeps, thickens at elbows and knees, and thins where the form turns away. These lines are not fussed; they are declarations, laid with a loaded brush that leaves ridges and slight breaks. Within them, Matisse draws again—short internal marks that nudge a fold or indicate the crease at a hip. The contour behaves like the lead in stained glass: it contains the chromatic panes and makes them sing brighter. Because the line is so clear, Matisse can model sparingly; a few cool strokes beside a warm plane are enough to propose volume.

Brushwork and Surface

The painting keeps the history of its making visible. The background is scrubbed in with open strokes that let the canvas tooth breathe through, giving the green field a murmuring texture. On the body, strokes follow form—the long drag down a thigh, the curved sweep across a rib cage—so that touch and structure agree. Corrections remain legible: a ghost line at the calf, a recovered edge at the shoulder, a shifted knuckle. These traces animate the surface and remind us that the figure is constructed in real time through choices rather than revealed by illusion.

Light and Space

Light is generalized and even, a condition rather than a spotlight. The figure turns by temperature shift more than by cast shadow: warm toward cool, pale beside dark. Space is equally economical. The bench lip, the faint seam where the wall meets the ledge, and the cool field behind are sufficient to hold the body in a believable room. Instead of building a deep perspectival chamber, Matisse offers a shallow envelope that presses the figure gently forward while respecting the flatness of the canvas.

Sculptural Spirit

Matisse’s sculptor’s eye is everywhere. The abdomen is a shallow basin bounded by decisive edges; the thigh reads as a cylinder with a single, confident highlight; the breast is a rounded shield turning by abrupt value shifts rather than by soft gradations. The head, heavy with hair, becomes a compact block whose planes catch light at cheekbone and brow. The whole figure feels carved and then painted—built from blocks and softened by the breath of color—an approach that lends the nude monumentality without size.

The Face as Mask

The face is reduced to essential planes: dark sockets, a straight bridge of nose, a small wedge of mouth. This mask-like treatment, common in Matisse’s work from these years, concentrates emotion rather than inflating it. The slight tilt and the calm set of features establish a mood—thoughtful, inward, composed—while freeing the rest of the body to carry expression through posture. By refusing anecdotal detail, the painting keeps the viewer’s attention on relations of weight, balance, and temperature.

The Bench and the Edge

The bench is more than a prop; it is a measuring device. Its hard line across the field flattens the space and provides a crisp counter to the organic contour of the body. Where the hands meet the bench lip, Matisse loads the paint darker, insisting on contact. The left hand drapes over the edge with two or three decisive angles; the right hand, set back, becomes a pale block with dark joints. These points of contact are the composition’s pressure points—the places where gravity is negotiated—and they quietly ground the whole scene.

Background Bands and Atmospheric Field

The background’s broad bands are used with architectural intelligence. The green field, brushed with subtle verticals, keeps the air cool and deep; the narrow ocher at right repeats the warmth of the figure and prevents chromatic isolation; a faint, darker stripe near the bench suggests the room’s corner without building a literal corner. These planes are not decoration; they are the walls of the picture’s house, built from hue rather than from lines of perspective.

Material Scale and Proximity

The scale of the figure within the frame encourages intimate viewing. From a step away, the roughness of contour and the scumble of the ground become palpable; from a few steps back, those same marks resolve into clarity and calm. Matisse calibrates the experience so that the viewer can oscillate: first sensing the tactile facts of paint, then reading the body as volume and posture, then returning to the living edges where those two realities meet.

Relationship to Earlier Fauvism

The canvas carries Fauvism’s lesson—that color can build a world—while declining its fireworks. Instead of complementary clashes across the whole surface, Matisse parcels intensity: the body’s warm notes against the cool room; a handful of near-black joints against mid-tones; a measured ocher echo at the right. The restraint produces dignity. It allows the nude to be modern without spectacle, present without provocation, and it points toward the poised interiors Matisse would soon paint where color fields become architecture and figures quietly inhabit them.

The Viewer’s Path Through the Picture

Matisse designs an itinerary for the eye. We enter at the face, drawn by the tilt and the strong hair mass, descend along the left contour to the hand, cross the bench lip, and then climb the inner arc of the legs to the small highlight at the knee before returning to the torso. This loop is smooth because each segment answers the last: curve to straight, warm to cool, dark to light. The journey is musical, all phrase and cadence, with no dead ends.

Poise, Modesty, and Agency

Although the figure is nude, the painting avoids voyeurism. The downward tilt of the head, the solidity of the seated pose, and the lack of theatrical props signal a worklike session between artist and model rather than a staged display. The hands claim the bench; the body claims the space. The viewer is invited to share the painter’s task—to read structure and color—rather than to project narrative or desire onto the figure.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Placed beside other nudes from 1907–1908, Seated Woman occupies a middle ground between the hot, outdoor blaze of The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) and the somber interior hush of Nude Wearing Red Shoes. It shares with both the commanding contour and the sculptural conviction, but it distinguishes itself through the seated pose and the cool atmosphere that allows the warm flesh to glow without aggression. It also prefigures later interiors where benches, screens, and color bands provide the simplest possible architecture for human presence.

Lessons for Looking

The painting offers a method for viewers: start with structure, not story. Notice how a single contour can declare the weight of a thigh; how a shift from ocher to green can carve a plane; how a bench line can anchor a body more surely than a detailed room ever could. In Matisse’s hands, simplicity is not lack but concentration. The economy of means invites attention to the essentials, and in that attention the figure becomes newly vivid.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Seated Woman endures because it proves that monumentality can be intimate, and that clarity can be tender. It models a path for modern figure painting that sidesteps academic finish and sensational display alike. Artists still learn from its limited palette, its reliance on line, and its trust that a few truthful planes can carry a complex presence. Viewers still find in it a humane gaze—neither cold analysis nor sentimental narrative, but the steady, respectful act of seeing.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Seated Woman is a quiet keystone in his move from Fauvist blaze to sculptural poise. A woman sits on a narrow bench, her body articulated by confident line and warm, breathing color against a cool, simplified room. Everything unnecessary falls away; what remains is balance, gravity, and the slow intelligence of looking. The painting does not shout; it concentrates. In that concentration it achieves what Matisse most valued: a durable harmony where color, contour, and plane hold a human presence with clarity and grace.