Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

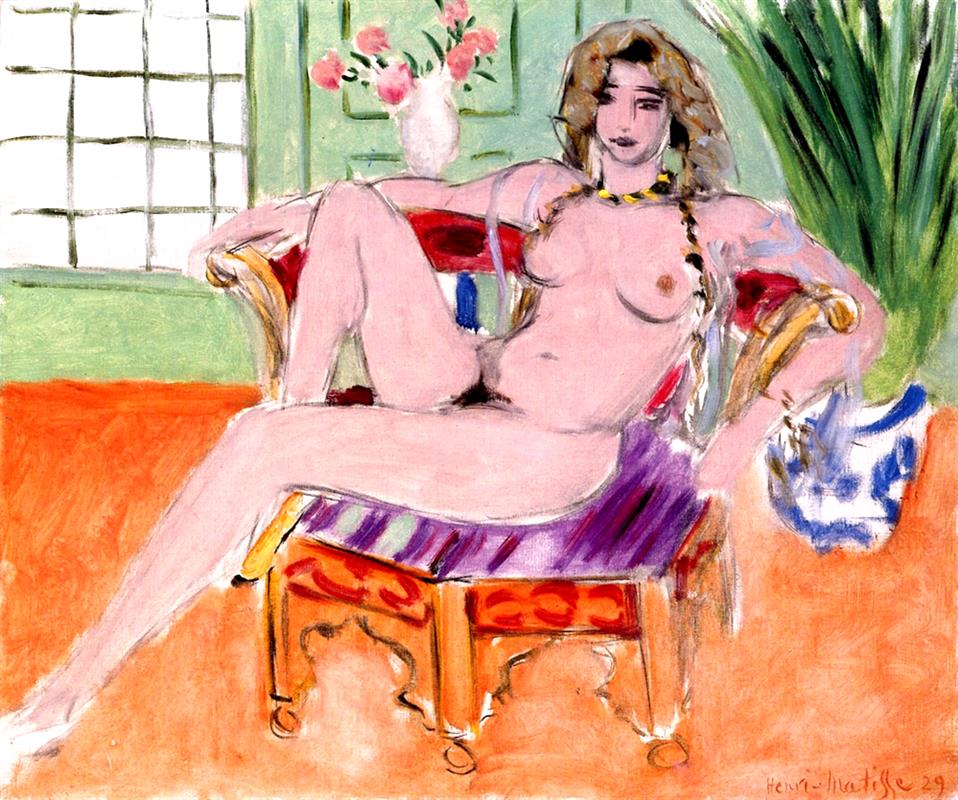

Henri Matisse’s “Seated Odalisque” from 1929 captures a climax of his Nice-period exploration of pattern, pose, and the architecture of color. A model lounges across a small, ornate sofa whose gilded arms flare like scrolls. Her long legs extend diagonally, one thrown over the seat’s purple-striped cushion, the other reaching toward the glowing orange floor. Behind her, a mint-green wall holds a gridded window and a tall plant whose dark fronds counterweight the figure’s pinks and violets. A white vase of pink flowers hovers near her head, while at the right edge a blue-and-white ceramic vessel repeats the cool notes of the window’s panes. The room is shallow and theatrical, yet nothing feels staged for drama; rather, the painting offers equilibrium achieved by measured intervals of color and contour. This odalisque is less a fantasy than a lucid demonstration of how differences—warm and cool, curve and grid, body and ornament—can be tuned into harmony.

The Nice Period Setting And Its Stakes

By 1929 Matisse had spent nearly a decade in Nice, converting rented rooms into portable theaters of light, textiles, mirrors, and screens. The odalisque motif gave him permission to populate these interiors with divans, striped cushions, ceramics, plants, and jewelry that could be rearranged at will. The subject was never ethnography; it was a grammar. In “Seated Odalisque,” that grammar is distilled into a few essential components: a radiant floor, a cool green envelope of wall and window, a central stage of upholstered furniture, and a figure whose relaxed authority organizes the whole. The stakes of the painting are not narrative but structural—how to keep a surface alive and readable when depth is compressed and color is asked to do the heavy lifting.

Composition As A Theatre Of Vectors

The painting’s order rests on the interplay of a few decisive vectors. The most commanding is the diagonal of the model’s legs, which cuts from the lower left into the center and then angles back toward the right arm. This slant converts the sofa into a platform and asserts the human body as the primary axis. A second vector runs horizontally along the seat’s front rail, its red-and-gold molding acting like a stage apron. A third, vertical vector is supplied by the plant at the right, whose upward thrust balances the recline. The gridded window contributes a system of perpendiculars that stabilize the picture and keep the arabesques from melting into decoration. These elements meet at the figure’s torso and head, which Matisse positions near the geometric center so that the curved arms, necklace, and face become a hinge for the surrounding furniture and walls.

Color As Architecture And Atmosphere

Matisse constructs the room with color as boldly as an architect would with walls. The orange floor is not mere ground but a radiant field that warms the entire foreground and sends light up into the body’s pinks. The walls are painted in a cool, chalky green that quiets the space and clarifies the silhouette. Across these complementary fields he lays chords: the violet-lavender of the cushion, the bursts of red on the upholstery, the gold of the carved legs and armrests, the mint-white of the vase, the cobalt patterns on the pitcher at right. Flesh is built from modulated coral and rose, cooled with blue and lilac in the shadows. Because hues borrow from neighbors—the green wall cooling the contour of the right arm, the orange floor ripening the thigh—the palette breathes as a single climate. The whole room reads as a balance of temperature, with warm floor and skin held in check by the cool wall, window, and ceramics.

Pattern, Ornament, And The Discipline Of The Decorative

In Matisse’s hands, ornament is not afterthought but discipline. The sofa’s cushion is striped in alternating violets, whites, and small red flashes; the repetition provides a steady rhythm against which the languor of the pose can unfurl. The gilded scrolls of the armrests echo the curving line of the model’s braid and the tilt of her head, completing a refrain of arabesques across the center. The grid of the window is just as important: it slows the upper left quadrant into a calm meter, preventing the arabesques from dominating. Pattern functions like meter in poetry or time signature in music—it regulates the flow so the melody can be heard.

Drawing And The Breathing Edge

The authority of the painting resides in its contours. Matisse draws the figure with a line that tightens and relaxes, as if tracking breath: crisp at the wrist where the hand rests on the gilded wood, looser along the shin where light erases distinction, firm again around the sternum and jaw. The facial features are simplified but exact, a few dark turns for eyes, nose, and mouth, sufficient to place the face without fixing it into portrait. The sofa’s edges are sketched in strokes that admit the texture of the canvas, so that while the furniture reads as solid, it also participates in the living surface of the paint. Everywhere the edge acts like a seam between color fields rather than a prison wall; the viewer can feel the give of the form.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The Nice light is diffuse and kindly, and Matisse uses it to compress the value range so color can carry volume. There are no black shadows. Instead, lilac and cool blue settle along the underside of the thigh and in the hollows of the shoulder. Warm peach gathers where the floor’s orange reflects into the skin. Gold accents on the furniture pick up white highlights, but even these are measured; nothing gushes or glitters. The light is not dramatic because the drama belongs to arrangement. This diffusion lets the viewer move without glare from window to vase to face to leg, verifying relations rather than chasing spotlight.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Depth is shallow by design. The floor rises like a carpeted stage; the sofa is a low platform; the wall and window sit close behind. Overlaps—arm over armrest, hair over shoulder, vase in front of window—do the work of persuasion. Linear perspective is muted because Matisse wants the eye to stay on the surface, where color and contour are negotiating. This productive flatness ties the painting to his late cut-outs, where interlocking shapes and decisive seams do all the thinking. Here, as there, meaning is produced at the meeting of edges.

Furniture And Objects As Actors

The sofa is the painting’s principal secondary actor. Its carved legs step forward with a balletic articulation, each foot curling under as if poised to move. The cushion’s violets and whites modulate the figure’s pinks, giving the body a harmonic bed. The white vase of pink flowers is not bouquet-as-symbol but a tonal bridge between wall and skin, a cool white that contains warm centers. The blue-and-white vessel at the right repeats the window’s blues and strengthens the cool chord. Together these objects establish intervals, keeping the composition in tune like instruments within a chamber ensemble.

The Model’s Agency And The Tone Of The Room

Matisse’s odalisques are often discussed in terms of fantasy, but the agency of this model is readable in pose and placement. She occupies the chair the way an owner occupies a room, leaning back with a confidence that is social rather than theatrical. The slight tilt of her head and the steady gaze meet the viewer without pleading. Jewelry is present but briskly indicated; the short necklace is a rhythmic series of dabs as much as an accessory. The room feels hospitable and conversational, not voyeuristic. The painting’s pleasure is the eye’s, not a narrative’s.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse’s pictures are built to be read like music. The orange floor sustains a long, warm drone. The cushion stripes supply a bright ostinato. The grid of the window beats in soft quarter notes. The curving armrests and legs of the sofa sketch a melodic phrase that echoes in the figure’s limbs. The plant’s vertical fronds are syncopations that nudge the rhythm upward at the right margin. The eye’s path is orchestrated: from the window’s squares to the vase’s white, across the face and necklace to the violet cushion, down the long leg to the floor’s glow, and back through the blue pitcher to the plant’s green and the wall’s mint. Each cycle discovers fresh harmonies, like variations on a theme.

Handling, Texture, And The Differentiation Of Surfaces

Matisse differentiates materials not through laborious description but through tailored touch. Skin is laid in creamy, even passes that knit into a single field with modest internal shifts. The gilded wood of the sofa is painted with shorter, denser strokes, letting red underpainting flicker through the golden ochres. The cushion receives firmer, flatter sweeps so stripes read as fabric under tension. The wall is a translucent wash that lets earlier layers breathe, while the plant is written in swift, dark, calligraphic gestures. This variety keeps the picture sensuous while maintaining allegiance to the flat plane.

Dialogues Within The Oeuvre

“Seated Odalisque” converses with several canvases from 1925–1929. It shares with the violet-toned odalisques the reliance on cool-warm polarity and the use of ceramics and flowers as tuning forks. It echoes the gridded backdrops of 1928–1929 still lifes, where squares, stripes, and color bands regulate an otherwise lush surface. Compared to the sumptuous pattern storms of 1925, this painting is clearer and more architectural; compared to the gray-blue austerity of “The Abduction of Europe,” it is warmer and more domestic. It foreshadows the large-cut-out interiors of the 1940s in its decisive shapes and its belief that ornament can bear thought.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Harmony

The serenity on the surface is the outcome of trial. Pentimenti are visible at the contour of the left leg and at the backrest where sofa meets wall, showing that Matisse moved edges to find a more persuasive balance. The right hand’s knuckles have been reinforced to keep attention from fraying at the margin. A violet shadow under the thigh is scumbled to avoid merging with the cushion stripes. Such restatements testify to the search for intervals that would cooperate. Equilibrium here is achieved, not given.

Psychological Temperature And Viewer Experience

The room’s temperature is hospitable. The warm floor invites the eye to settle; the cool wall offers rest; the figure provides focus without insistence. The entire scene seems designed for returning attention. One can linger at the tiny conversation between a necklace bead and a gold scroll, or at the place where mint-green steals a touch of blue from the window. The painting’s mood is not ecstatic but companionable. It teaches a way of looking in which the pleasures are structural and renewable.

Why The Painting Endures

“Seated Odalisque” endures because it converts difference into cooperation. Warm floor and cool wall; soft body and carved wood; grid and arabesque; the improvised and the architectural. Each pair finds a workable truce on the painted surface. The result is a poised interior whose pleasures do not depend on novelty. Instead, the painting offers clarity—of color, interval, and touch—that can be rediscovered with every viewing. It is a picture about how to make a room for attention.

Conclusion

In 1929 Matisse condensed years of studio testing into a lucid interior where a seated odalisque presides over a balanced ensemble of orange, mint, violet, gold, and blue. The composition is a theater of calibrated vectors; color acts as architecture; pattern supplies meter; contour breathes; light is kind. Nothing is extraneous, yet the scene feels generous. The painting proposes that the decorative, far from being superficial, is a rigorous system for distributing care across a surface. In its calm, modern way, “Seated Odalisque” is a manifesto for the intelligence of pleasure.