Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

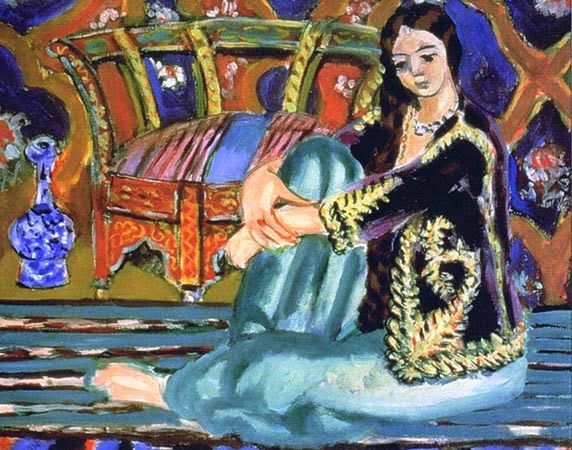

Henri Matisse’s “Seated Odalisque” (1928) distills the spirit of his late-Nice interiors into a tableau where color is architecture and pattern is rhythm. A young woman sits on the floor with her knees drawn up and arms looped around her shins. She wears loose turquoise trousers and a black velvet jacket lavishly trimmed with gold embroidery; pearls glint at her throat. Behind her unfurls an ornamental world: a scalloped, trellis-like wall of violet, blue, and russet; an arched, inlaid bench with salmon and cerulean cushions; and at the far left, a blue bottle or ewer that catches the room’s cool light. Across the foreground, wide stripes run like musical staves. The composition is intimate and frontal, yet the space feels ceremonial, even theatrical. Matisse arranges every element so the figure can rest in a climate of saturated color without surrendering her quiet autonomy.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Ideal

By the late 1920s Matisse had refined the experiments of Fauvism into a classicism of intervals—strong hues spaced with care; shallow, tapestry-like rooms where objects behave like chords; and models posed not for narrative but for clarity. Nice offered the Mediterranean’s steady light and the privacy of hotel-studio interiors that could be staged with screens, textiles, and portable furnishings. The odalisque theme supplied a permissive frame for languor, drapery, and pattern. In “Seated Odalisque,” however, the emphasis shifts from reclining sensuality to mindful presence. The sitter’s upright, folded pose, her lowered eyes, and the containment of her limbs convert the room from harem fantasy to modern chamber, a place for attention and repose.

Composition As A Calm Engine

The composition is built on nested curves and countered by measured horizontals. The sitter’s body forms a compact oval—knees, forearms, and face circling a central emptiness—that rests on the striped floor. Behind her, the back of the bench traces a flamboyant arc that repeats and enlarges the figure’s curve, creating a halo-like cradle. The ornamental wall sets a sequence of interlocking lobed shapes, each one a soft quatrefoil, that extends the logic of curves to the perimeter. To keep this lyricism from floating away, Matisse anchors the image with stripes across the floor, the bench’s straight lower rail, and the vertical accent of the blue ewer at left. The eye moves in looping circuits—ewer to bench, bench to face, face to clasped hands, hands to stripes—never snagged, never rushed.

Color As Structure And Temperature

Color here is both temperature and architecture. The overall climate is warm, driven by russet, orange, and rose on the wall and bench, but it is cooled decisively by pools of blue and turquoise: the trousers, the bench cushion, the bottle, and the shadowed violets in the wall’s medallions. The black jacket trimmed with gold mediates between heat and cool, absorbing and re-radiating the surrounding palette. Flesh tones are apricot and shell-pink tipping toward olive in shadow; tiny pearly lights insist on the evenness of Nice studio illumination. Because hues borrow from their neighbors—a teal reflection riding the trouser folds; a rose warming the cheek; a greenish echo in the bottle’s glass—the palette breathes. Nothing screams, even when the contrasts are bold.

Pattern As Meter And Memory

The room is saturated with pattern, yet none of it is gratuitous. The wall’s scalloped modules meter the whole surface like a slow ostinato; the bench cushion’s stripes, the foreground bands, and the jacket’s embroidered scrolls supply quicker beats; the pearls around the neck add a delicate ostinato at the top of the register. Pattern is not surface chatter—it is the instrument that paces attention. It also carries memory. The lobed wall evokes Moroccan architectural tracery; the gold trimming recalls textile craftsmanship; the bottle and bench repeat motifs seen across Matisse’s Nice interiors. The room becomes a condensed anthology of the objects he loved to paint, now tuned to support rather than overwhelm the sitter.

The Figure’s Pose And Modern Agency

Unlike the languid, prone odalisques of 1925–1927, this model sits firmly in her own gravity. The posture is self-containing: legs drawn in, hands clasping, torso tilted slightly forward as if listening inward. The softened triangle of face, with its lowered gaze, is composed but not coy. She is visible without performing. The trousers’ volume and the jacket’s weight add to a sense of modern agency, shifting emphasis from exposed flesh to the composed intelligence of bearing. Even the pearls read less as luxury than as rhythm—small measures that echo the embroidery’s cadence.

The Bench, Bottle, And Floor As Supporting Voices

Three nonhuman actors steady the drama. The arched bench is a brilliant stabilizer: its flamboyant back frames the sitter, its vermilion sides deliver weight to the left, and its cool cushion aligns with the trousers to relay blue across the center. The blue bottle at far left declares the room’s cool axis in one compact silhouette; its patterned skin repeats the room’s decorative grammar at miniature scale. The striped floor offers the clearest horizontal in the painting, preventing the composition from tipping into ornamental turbulence. Together they form a triad—bench, bottle, stripes—that keeps the figure grounded.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

Light is even and reflective, a hallmark of the Nice studios. There is no theatrical spotlight; instead a broad, breathable illumination lets color carry volume. Shadows are chromatic—a violet gray under the chin, greenish cools within the trouser folds, warm browns under the bench. Highlights are small and exact: a milky dot on a pearl, a pale ridge along the shin, a touch of light on the bottle’s shoulder. Because the value range stays moderate, saturation remains high without fatigue; the viewer’s eye can dwell without squinting.

Contour And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s drawing holds the composition together. The outer contour of the figure is elastic: it tightens at the ankles and wrists, eases along trouser bulges, and softens at the cheek’s contour. The bench’s arabesques are drawn with calligraphic pressure that asserts the hand over geometry, keeping ornament alive. The bottle’s profile is a single, confident turn, its interior pattern a few abbreviated scrolls—enough to convince without fuss. These living edges ensure that the large color planes feel handmade and humane.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Space is shallow and intentional. The bench, wall, and floor behave like interlocking screens. Overlaps—figure against bench, bench against wall, bottle against background—persuade depth, but perspective is otherwise suppressed. This productive flatness directs attention to the surface, where the real interplay occurs: curve against stripe, warm against cool, pattern against plane. The room is less a window and more a tapestry one steps into with the eyes.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

The painting rewards slow, musical looking. The wall sustains a slow beat; the floor keeps a regular march; the embroidery flickers at a faster tempo; the pearls tick lightly; the bottle and bench strike resonant chords at measure points. The eye traces repeating routes: bottle to bench to face to hands to stripes and back; or wall medallion to jacket braid to pearls to bench cushion to trouser fold. On each pass, new consonances emerge—a blue caught in the bottle that reappears as a cool inside a shadow; a gold braid answering a bench inlay; a rose bloom in the wall echoing the flush in the cheek. The image becomes a score: not noisy, always alive.

Cultural Frame And The Ethics Of Ornament

Matisse’s odalisque imagery sits in tension with Orientalist histories. What distinguishes this canvas is the redistribution of dignity. Ornament is not weaponized as exotic spectacle; it is the room’s structural logic. The figure is not a passive emblem but a calm center—clothed, composed, and granted the same clarity of handling as the bench and bottle. The decorative is treated as a universal language of spacing and rhythm rather than an ethnographic label. The result is a modern interior in which pleasure, attention, and respect are coextensive.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Seated Odalisque” converses across Matisse’s 1920s. With “Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background” it shares the trellised wall and arched furniture, but here intimacy replaces monumentality. With “Playing Chess” it shares a seated figure and patterned surround, though the present canvas dispenses with tabletop anecdote to focus purely on posture and climate. Compared to the earlier, hotter odalisques, the color here is more intermixed—violets and teals complicate the reds—and the contour more meditative. At the same time, the broad, flat planes and clipped silhouettes anticipate the logic of the late paper cut-outs, where figure and ground become interlocking color shapes.

Materials And The Intelligence Of Touch

The paint’s handling differentiates materials with remarkable economy. The jacket’s velvet is laid in thicker, darker masses, then braided with swift, bright strokes to simulate metallic embroidery. The trouser fabric is all elasticity: long, supple passes curve around the knees and slump into resting folds. The bench reads as lacquered wood through denser, glossy passages; the bottle’s glassiness is achieved by thin, translucent blues that let undercolor glint. Skin is knit with smoother, creamy strokes and set off by slender, warm contours. The variety of touch keeps the surface sensuous while preserving overall clarity.

Evidence Of Process And The Earned Harmony

Close looking reveals small revisions: a softened edge where a trouser fold was moved; a restated stripe to adjust the floor’s cadence; a brightened braid to lock the jacket’s rhythm with the bench’s inlay; a corrected curve in the bench back to align with the figure’s silhouette. These pentimenti anchor the calm we feel. Harmony here is achieved, not automatic; the intervals have been tuned by hand and eye.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The prevailing mood is companionable and inward. The sitter’s lowered gaze and gathered limbs suggest self-containment rather than display; the surrounding room, though saturated, behaves like a supportive climate rather than a spectacle. For the viewer, the image offers a place to dwell. Each return reveals a fresh hinge: the pearl glint repeating in a braid highlight; a violet echoing in the shadowed cheek; a turquoise reflection entering the bottle; a russet bloom in the wall answering the bench’s leg. The painting sustains daily looking—the highest compliment for decorative art with intellectual ambition.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its satisfactions are structural and renewable. Strong differences—curve and stripe, warm and cool, black velvet and translucent glass—are spaced so that they cooperate. The figure holds the center without strain because the room is tuned to receive her: arcs cradle, stripes stabilize, colors reciprocate. The pleasure it offers is not a single effect but a network of relations that remain interesting under patient attention. It is both a record of a particular studio and a portable climate of calm.

Conclusion

“Seated Odalisque” is a lucid manifesto for Matisse’s belief that the decorative can carry thought. A young woman, gathered into herself, sits within an interior composed of interlocking curves, tuned colors, and measured patterns. Color acts as structure; pattern meters time; contour is a breathing edge; light is chromatic and kind. The result is an image that offers hospitality to the eye: a modern room where intensity and repose are not opposites but harmonized partners. In its poise and clarity, the painting shows how much can be said with a few well-placed intervals and a confidence in color’s ability to build a world.