Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

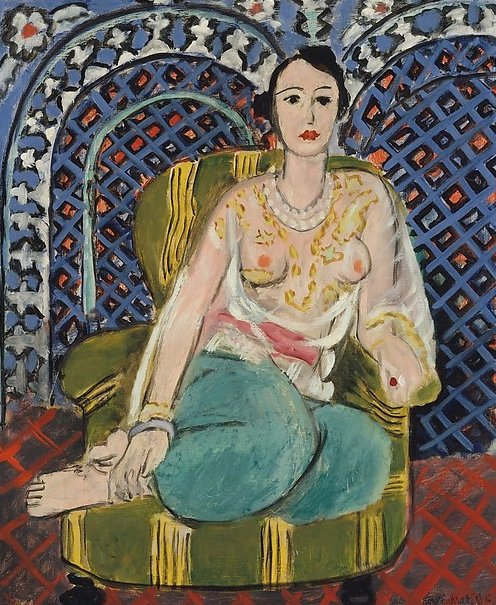

Henri Matisse’s “Seated Odalisque” (1926) is a quintessential statement from the artist’s Nice period, when the studio became a theater of color, textiles, and human presence. A model sits cross-legged on a deep green armchair, her torso draped in a sheer blouse glowing with floral touches and golds, her legs wrapped in turquoise trousers that gather and fold with sculptural weight. Behind her, an ornamental screen of indigo latticework and pale arabesques rises like a stage set. The tiled red floor pushes forward, flattening depth and turning the whole room into a patterned plane. Matisse’s subject is not an exotic narrative but the intelligence of relation—how figure, fabric, and backdrop interlock to produce a calm, durable harmony.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Turn

By the mid-1920s, Matisse had channeled the audacity of Fauvism into a modern classicism founded on measured intervals and long, breathable color chords. Working in hotel rooms and apartments along the Riviera, he staged models among screens, carpets, and simple furniture that could be rearranged like musical instruments. The odalisque became a flexible motif for this endeavor. It permitted relaxed poses, generous textiles, and a decorative atmosphere without the burden of anecdote. “Seated Odalisque” exemplifies this turn. The image is saturated with pattern and color, yet nothing feels crowded. The figure’s clarity and the room’s order make a poised, contemplative space where looking can proceed at an adagio tempo.

Composition As Armature Of Balance

The composition is built on a triangle whose apex is the model’s head and whose base stretches across the chair’s cushion and the planted foot. The right arm descends to the knee, the left foot folds under the opposite thigh, and these countering diagonals lock the torso into equilibrium. The chair, with its broad wings and striped upholstery, amplifies the triangular structure and frames the body in a cushioned heraldry. Behind, two arches of the blue screen repeat the triangular rhythm at a larger scale, while the red tile pattern lays a grid that steadies the lower register. This structural redundancy is deliberate; it allows the eye to circulate through similar shapes in different keys, binding the space.

Color As Architecture And Atmosphere

Color does the architectural work of the painting. The green armchair is not merely furniture; it is a major mass, a cool domain that holds the warmth of the figure. Yellow stripes on the upholstery echo the gold notes in the blouse, linking plane to body. The trousers form a broad lake of turquoise and blue-green, modulated with grays and soft shadows so that volume remains while the color stays luminous. The screen behind the model is a concert of blues—cobalt lattice glazed over indigo, with pale highlights that read as reflected light. That cool field both recedes and presses forward, an active tapestry against which flesh can register. Across the bottom, the terracotta and wine reds of the tile inject warmth back into the chord, their angled lines guiding the eye toward the chair’s base. Whites are pearly rather than stark; blacks are sparing and used to articulate features, jewelry, and a few structural edges. Nothing is pure; every hue borrows from its neighbor, which keeps the picture breathing.

The Figure’s Presence And Modern Agency

The model does not perform for a fictional harem. She sits with the sober dignity of a collaborator. Her head is upright, gaze level, mouth calmly set. One arm rests, the other hand cups the opposite knee, creating a closed circuit that holds energy in. The pose is sculptural, almost classical in its symmetry and restraint, yet it remains humanly relaxed. The sheer blouse—white cooled with lilac and warmed with pink and yellow floral marks—lets the body’s warmth appear without literalizing anatomy. The trousers, heavy and modest, ground the figure and resist theatrical sensuality. Matisse reclaims the odalisque from voyeurism and turns it into an instrument for modern poise.

The Authority Of Contour

Matisse’s line confers authority without heaviness. The jaw is a continuous curve, toughened near the ear; the nose is rendered as a single plane; the contour of the arm tightens over the elbow and relaxes along the forearm. The chair’s wings are drawn with confident, breathing edges that swell and thin, keeping upholstery alive. In the screen, lattice diamonds are established by economical strokes that never lock into mechanical repetition; they remain human marks. These lines do not imprison color; they give it a place to act. The figure’s silhouette stays legible even as patterns crowd the field, because contour has been attentively weighted.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The painting glows with Mediterranean light—diffuse, reflected, and generous. Shadows rarely sink to black. Cool violets and grays gather under the arm, along the knees, and in the folds of the trousers, shaping form while maintaining color. The blouse’s highlights are milky rather than chalk white, catching the light that bounces off the blue screen. Jewelry brightens in small dabs of pale tone, and the red of the lips holds a compact heat that answers the floor. The effect is a room lit from several soft sources rather than a spotlight. It is a climate more than an effect, one that lets color carry modeling.

Pattern As Structural Rhythm

Pattern is not applied decoration; it is structural rhythm. The blue screen’s diamonds act like a visual metronome, pacing the field with medium beats. The pale arabesques and medallion bands layered over the lattice supply a higher register of ornament, a lace that keeps the large blue plane from becoming inert. The chair’s stripes mark a slower tempo and seat the figure in a sequence of verticals that echo the screen while resisting it. The tiled floor supplies the lowest beat, a regular diagonal that asserts the plane beneath the chair. Together these patterns act like sections of an orchestra—percussion, woodwinds, and strings—supporting the solo line of the figure.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Space in “Seated Odalisque” is shallow by design. The chair presses close to the picture plane, the screen behaves like a wall tapestry, and the floor tilts forward. Yet the figure sits with convincing weight because overlaps and value changes create just enough recession: foot before cushion, cushion before chair wing, chair before screen. This productive flatness keeps attention on the surface where the primary drama—color against color, pattern against silhouette—takes place, while permitting the human body to occupy space persuasively.

The Green Chair As Pictorial Engine

The chair deserves special attention. Its green is mixed with yellow and olive notes that lift and settle across its bulges, so that the upholstery reads as substance rather than patch of color. The yellow stripes are not decorative afterthoughts; they lock the chair’s curves to the picture plane and restate the figure’s vertical axis. Moreover, the chair’s green modulates the turquoise of the trousers and the blues of the screen, acting as a hinge between warm and cool. In a room crowded with pattern, the chair is the great reconciler.

Tactile Intelligence And The Variety Of Touch

Matisse differentiates substances through touch. The blouse is laid with thin, scumbled paint that lets underlayers whisper, creating a persuasive gauze. The trousers are handled with broader, creamier strokes whose weight conjures gathered cloth. The screen’s lattice is painted with deliberate, repeated marks that stack like tiles, while its pale flourishes are dropped in with quick, calligraphic flicks. The floor’s red is dragged across the surface so the canvas tooth participates, implying the granular feel of fired clay. This tactile intelligence gives the painting body without illusionism. One senses not only how things look but how they might feel.

The Face As Compact Anchor

Amid the room’s saturation, the face remains a compact anchor. Features are simplified to planes and arcs—a dark hairline, the precise comma of an eyebrow, the small triangle of nose, the red punctuation of lips. This mask-like clarity is not impersonal; it is the means by which the face holds its own against the blue screen and green chair. The necklace circles the neck in small, even notes that cool the warmth of the lips and blouse, and a faint shadow at the jaw settles the head into space. The face’s gravity organizes the gaze. Whatever routes the eye takes across pattern and fabric, it returns to this center.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

The very word “odalisque” carries a history of Orientalist fantasy. Matisse acknowledges that lineage through costumes, screens, and carpets; he then redirects it. The model’s modern haircut, the frankness of paint, and the democratic treatment of figure and ground remove the subject from ethnographic spectacle. Here, the so-called exotic resides in color and pattern—domains that apply equally across person and room. The painting’s ethics lie in this redistribution. Every part of the canvas is granted dignity; no single element exists merely to decorate another.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse frequently compared painting to music. “Seated Odalisque” clarifies the analogy. The screen supplies a steady meter, the chair’s stripes offer slower pedal tones, the floor’s diagonals sustain a bass pulse, and the figure sings the melody. The viewer experiences the image by following these tempos: up through the screen’s arches to the head, down along the arm to the knee, across the cushion to the foot, and back again in a measured loop. Each circuit reveals new harmonies—a yellow in the blouse answering a stripe in the chair, a blue shadow on the trousers aligning with lattice, a red tile echoing the lips. The painting is built for prolonged listening with the eyes.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

This canvas speaks to several companions from 1925–1926. Compared with the reclining odalisques on striped divans, this seated variant emphasizes vertical balance and heraldic presence. With “Odalisque with a Tambourine” it shares the ornamental blue screen, but the present work trades overt movement for contained poise. In relation to still lifes like “The Pink Tablecloth,” it shares a pearly light and a reliance on a few strong accents to energize a quiet chord. Looking forward to the cut-outs, one senses how silhouette already behaves like cut paper, the figure reading as a single shape set into a patterned field. Across these dialogues, the painting confirms the continuity of Matisse’s project: to make the decorative a vehicle for thought.

Material Presence And Evidence Of Process

The surface carries the memory of work. Near the shoulder one can see a softened line where the contour was moved; in the screen a lattice diamond has been painted over and shifted to square with the arches; along the chair’s edge a dark drawing stroke peeks through green. These pentimenti deepen rather than disturb the calm. They reveal that equilibrium was reached through revision, not formula. The serenity projected by the final chord is the earned outcome of many small decisions.

Why The Painting Endures

“Seated Odalisque” endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return uncovers a fresh hinge: a turquoise half-tone on the trousers that recruits a cooler blue in the screen; a yellow stripe on the chair that realigns with a gold note in the blouse; a red tile that balances the lips; a small white glint on jewelry that keeps the head aloft. None of these discoveries exhausts the image because they are symptoms of a deeper rightness: the spacing of differences has been tuned so that the canvas holds together under repeated viewing. The room remains generous because its order is alive.

Conclusion

Matisse’s “Seated Odalisque” is not a tale of the exotic but a demonstration of modern harmony. A human figure, a green chair, a blue screen, and a red floor are arranged so that color becomes architecture, pattern becomes grammar, and contour becomes breath. The shallow space keeps everything near the surface where relations can be felt, yet the body sits with convincing weight. The result is a poised interior that invites slow attention and rewards it with consonances that continue to unfold. In this painting, the decorative is not superficial; it is the very means by which thought and pleasure become visible.