Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Odalisque

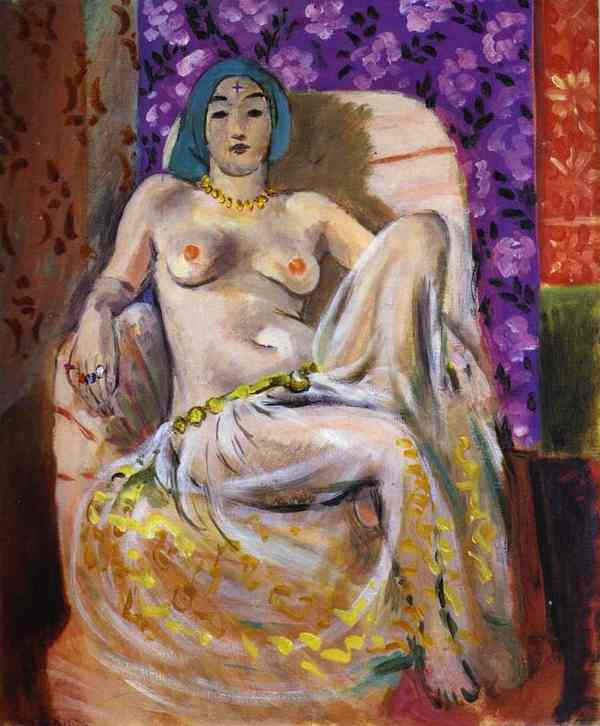

Henri Matisse painted “Seated Odalisque” in 1922, at the heart of his Nice period, when he turned modest hotel rooms into stages for color, pattern, and repose. During these years he explored the odalisque theme with unusual persistence, not to reenact harem fantasies, but to test how a reclining or seated nude, framed by saturated textiles and studio props, could become a finely tuned instrument for light and hue. The Mediterranean climate offered a soft envelope of illumination; secondhand shops and dealers supplied embroidered shawls, patterned screens, and jewelry; and a rotating cast of models gave him varied silhouettes upon which to orchestrate paint. This canvas belongs to that sequence yet stands out for its frontal authority: the sitter occupies a high-backed chair like a throne, surrounded by curtains and a violet screen that elevate the figure from private model to emblematic presence.

Composition As A Theater Of Planes

The composition is organized as a shallow, frontal theater. A large armchair fills the center, its pale upholstery setting a cool stage on which the body appears as a warm, luminous mass. Behind the chair a vertical panel of purple patterned textile anchors the background, flanked by strips of red and green at the right and a darker, rose-colored field at the left. These flat planes act like wings and backdrop in a small proscenium, pushing the nude forward without resorting to deep space. The figure’s pose generates diagonals that energize the rectangle: the left arm drops and bends at the wrist; the right arm arcs over the chair’s arm; the left leg rises beneath gauzy drapery while the right leg descends, forming a lively zigzag. A belt of beads or coins crosses the abdomen like a hinge, focusing attention at the body’s center before the eye resumes its circuit around the chair.

The Odalisque Pose And Modern Authority

The odalisque motif afforded Matisse freedom to show the nude as a self-contained architecture rather than a narrative character. Here the model faces nearly frontally, chin lifted, eyes half-lidded, shoulders open. The pose is relaxed yet sovereign, a studied balance between ease and command. Jewelry at neck and waist and the ringed hand emphasize joints and pivots rather than status; they punctuate the long curves with small, bright accents that assist the eye. The body’s mass is mapped with soft temperature shifts rather than hard chiaroscuro, so that flesh reads as breathing surface. Drapery is not modesty’s veil but an active contour that describes the lifted thigh and the chair’s seat while staging an elegant cascade at the picture’s right.

Color Chords And The Temperature Of Pleasure

The palette is tuned to a warm–cool duet moderated by the room’s textiles. The figure’s flesh carries apricot and rose notes cooled by bluish grays in shadow; the chair is milky beige with violet half-tones; the background unfolds as a saturated violet patterned field against which red and green panels flare in narrow bands. The drapery is pearl white shot with cool grays, while the skirt or cushion at the base glows with yellows and citrons that catch stray light. Against these orchestral areas, jewelry appears as compact sparks—gold and ultramarine at the necklace, small blue stones at the ring—tiny, decisive notes that enliven the chord without tipping it toward glitter. The temperament of the whole is generous warmth contained within cool architecture, a climate in which color saturates yet never blares.

Pattern As Architecture Rather Than Decoration

Pattern saturates the setting but serves structure. The violet screen blooms with floral motifs that repeat at measured intervals, stabilizing the back plane and preventing it from dissolving into emptiness. At the right edge a red panel with small floral marks and a green block stacked beneath it work like vertical piers that frame the stage. These patterns are never fussy; they are painted with broad, confident marks whose slight variations keep the surface alive. Ornament becomes a means of building space and distributing weight. The patterned world does not compete with the body; it receives it and gives it scale.

Light As A Continuous Veil

Light arrives as a soft, coastal veil rather than a spotlight. The pale chair seems to reflect illumination upward into the torso and drapery, causing local highlights to bloom without glare. Shadows are colored rather than black: cool gray-violets lodge under the breast and along the rib cage; greenish notes cool the drapery where it turns away; warmer browns settle at the chair’s base. Because light remains continuous, color carries emotion. The figure feels present and breathable, not carved from darkness. This is the Nice-period ideal: a room bathed in even light that allows the painter to speak with temperature instead of theatrical contrast.

Drawing Inside The Paint

Matisse draws here with the pressure of the loaded brush. The shoulder line thickens and thins, catching bone and soft tissue with a single pass. The right hand is a few supple angles set against the chair’s pale plane; the left hand, gripping the arm, is summarized by knuckle notations and a ring flare. The head’s contour is crisp but elastic, giving the features room to breathe. Eyebrows, nose, and mouth are calligraphic, interior accents that set the mask-like calm of the face. The drawing’s authority comes from restraint: no detail interrupts the large rhythms, yet nothing essential is omitted.

Drapery As Moving Contour

The gauze that passes over the thigh and spills down the side is a major actor. It tracks the leg’s rise, pools into folds that echo the chair’s curves, and flashes with citron tassels and gold flecks that dance across the lower register. These tassel strokes form a repeating border that rhymes with the floral repeats behind, knitting figure to setting. In places the drapery deliberately loses descriptive clarity and becomes pure paint, a cascade of grays and whites swept by the brush’s belly. This alternation—between convincing fabric and abstract flow—keeps the surface endlessly readable.

Space Built By Planes And Overlap

Depth is shallow and deliberate. The chair’s interior, the figure, and the backdrop sit like consecutive panels stacked close together, each clarified by overlap rather than by measured perspective. The right leg projects slightly forward, catching a deeper shadow that grants a hint of protrusion; the left arm rides the chair’s arm and uses the ring to announce the near edge. The background’s strips create side aisles that prevent the composition from ballooning. Matisse avoids recession in favor of presence; everything needed for a full experience of the body and room occurs within arm’s reach.

Brushwork And The Velocity Of Touch

The handling is brisk and frank. Across the chair you can see soft, sweeping strokes laid wet into wet; across the screen the brush deposits thicker, patterned touches that sit like velvet on the surface; across flesh the paint thins into pearly veils for translucent volume. This variability of touch—heavy, then quick; opaque, then transparent—enlivens every zone. The viewer reads not just image but process, the tactile record of decisions made at a human pace.

Ornament, Costume, And Their Meanings

The odalisque genre carries a historical freight. In the nineteenth century it often staged fantasies of the “Orient” for European eyes. Matisse, studying Islamic art and collecting textiles, found in these materials not exoticism to reenact but abstract intelligence to learn from—repeating geometry, carpet medallions, calligraphic rhythms, a belief that pattern could be architecture. In “Seated Odalisque” the jewelry, coins, and headscarf are signs, but the painting refuses anecdote. The model’s modern haircut altered by a cool headwrap and the commanding pose keep the scene anchored in studio reality. The elements from Ottoman or North African dress become visual tools that permit saturated color, metal glints, and ornamental edges to coexist around a figure without clutter.

The Head As Mask And Likeness

The face is simplified to an iconic mask—arched brows, almond eyes, straight nose, small firm mouth—but it is not impersonal. The cool teal of the headwrap cools the forehead and heightens the warmth of cheeks and lips. A small cross-like mark at the headwrap’s center reads as seam or ornament and stabilizes the vertical axis of the composition. Necklace beads echo the head’s small darks, binding top and torso. This mask-like clarity is a signature of Matisse’s Nice portraits: he wants faces that can hold their own against vibrant fields of pattern and color.

Rhythm, Repetition, And Visual Music

The painting’s pleasure lies in rhythm. Petal motifs repeat in the purple field; tassel dashes repeat around the lower edge; bead circles repeat at neck and waist; curving chair arms repeat the body’s curves. These repetitions create a steady beat that guides the eye. The path is reliable: enter at the luminous torso, descend the drapery to the tassels, rise along the chair’s curve to the jewelry at the hand, cross the breastbone to the necklace, then ascend to the face and headwrap before drifting back through the violet pattern. Each lap reveals a new color echo or brush inflection, making the image a score that can be reread indefinitely.

Material Presence And Tactile Cues

Despite simplification, the scene is tactile. You feel the soft nap of the chair where paint is dragged lightly; you sense the drapery’s cool slip in the long gray sweeps; you perceive the coin belt’s small relief where thicker yellow strokes sit proud of the surface; you register the smoothness of skin where paint thins to pearly films. These cues anchor the visual music in the body’s memory of touch and keep the picture from becoming merely decorative.

Comparisons Within The Odalisque Series

Placed beside other 1922 interiors, this work is a fulcrum between calm rooms and more extravagant harem fantasies. Some odalisques recline languorously on divans amid carpets; “Seated Odalisque” chooses the erect, frontal seat and a stricter proscenium built from three or four big planes. The color is saturated but not explosive; the drawing is assertive but not hard. It anticipates the increasing clarity of the 1930s portraits while preserving the lush envelope of Nice.

Psychological Weather And The Poise Of Ease

The emotional tone is clear and poised. The sitter neither beckons nor withdraws; she occupies the chair with an ease that reads as self-possession. Pattern and color intensify the scene without unsettling it. The room is warm enough to admit pleasure and cool enough to sustain attention. This dual temperature—sensual and lucid—explains why the painting continues to feel modern. It offers a vision of bodily presence that is neither sentimental nor clinical, neither coy nor confrontational.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

The image structures a loop of attention that lengthens time. The eye lands on the bright torso, traces the diagonal to the lifted knee, plays among tassels and drapery edges, rises along the chair, pauses at the jewelled hand, crosses the necklace to the face, then drifts back through the purple pattern to begin again. Each circuit is slightly altered by small discoveries—a cooler gray under the breast, a hotter yellow among the tassels, a faint red seam in the chair. The painting does not exhaust itself; it teaches how to keep looking.

What The Painting Offers Today

“Seated Odalisque” offers a durable lesson in how color, pattern, and figure can be integrated without theatrics. Designers find in it a primer on balancing saturated fields with pale grounds; painters learn how to draw inside paint and how to make ornament carry structure; viewers encounter a humane tempo of seeing in which beauty is not noise but relation. The painting’s frank modernity lies in this ethic of attention: it proposes that sensual pleasure and compositional intelligence need not be opposites.

Conclusion: Presence Held By Pattern And Light

Matisse’s “Seated Odalisque” condenses the Nice period’s ideals into a compact theater of presence. A frontal figure sits in a pale chair; violet, red, and green planes frame the stage; jewelry and gauze provide small, quick notes; and light arrives as an even kindness that lets color do the speaking. Pattern acts as architecture, brushwork records the body’s speed, and the nude becomes a clear, self-possessed chord within a room tuned to pleasure and calm. The painting remains a touchstone for how modern art can honor the body and the eye at once.