Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

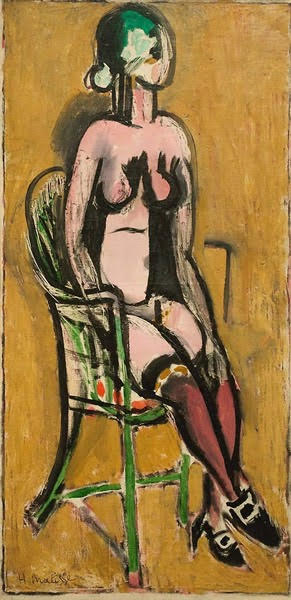

Henri Matisse’s “Seated Nude with Violet Stockings” (1914) arrests the eye with a fierce economy. A tall, narrow canvas holds a single figure perched on a green wicker chair before an ochre ground that behaves more like parchment than room. The nude’s body is mapped by thick black contours; limbs and torso are simplified into assertive planes of pink, gray, and inky black. Violet stockings surge up the legs like columns of color, ending in blunt, black-and-white shoes that declare a modern studio rather than a pastoral bath. The face, scored with emerald and shadow, reads as a mask—deliberately impersonal, a reminder that Matisse is not chasing likeness so much as the decisive architecture of the human form. The painting is lean, urgent, and startlingly contemporary, a hinge between the decorative orchestration of his pre-war interiors and the cool, sunlit harmonies of the Nice period to come.

Historical Moment and Studio Conditions

Painted at the threshold of the First World War, the work belongs to a short but intense phase in which Matisse compressed color and line into a tougher, more structural language. The Tangier journeys of 1912–1913 had taught him to think in large, unmodulated fields; back in Paris and Issy-les-Moulineaux, he turned that clarity inward, testing how much of a figure could be carried by contour and the fewest possible tones. At the same time he was developing the monumental “Bathers by a River” and revisiting sculpture, both of which encouraged him to treat the body as an architecture of masses rather than a vessel for anecdote. “Seated Nude with Violet Stockings” absorbs these pressures. Its palette is reduced, its drawing emphatic, and its surface frank about its making. It feels like a studio decision rendered with the speed and conviction of a verdict.

First Impressions and the Power of Format

The extreme vertical format matters. It forces the viewer to register the figure head-to-toe as a continuous column, like a standing kakemono scroll translated into Western oil. The chair occupies the lowest third, a green lattice that braces the figure’s weight. Above it, the torso narrows and sways, capped by a head tipped slightly back into light. Nothing crowds the field: no drapery, no window, no table of props. The ochre ground is a plane, not a room, which throws the entire burden of interest onto the junctions of line and color that define the body. This is a painting you read from edge to edge, not just from face outward.

Composition and Pose

The pose is classic and unconventional at once. One leg crosses over the other, the right knee projecting forward, the shin sheathed in violet that stops abruptly at the garter. The torso twists slightly, flattening the stomach into a pale panel while pushing the ribcage into relief. Arms hang with a studied neutrality that keeps the silhouette clean. The chair’s ellipse echoes the arcs of hip and shoulder, and the vertical cane supports rhyme with the columnar stockings. Matisse composes with interlocking arabesques and struts: soft curves for flesh, straight accents for furniture and stockings. The result is a taut balance of yielding and insisting, of body and scaffold.

Color Architecture

Though the palette is sparse, it is strategic. Ochre surrounds everything, a warm field against which cool notes can flare. The chair’s green, unusual and saturated, is not descriptive; it is a complementary antagonist to the pinks and violets of the figure. The stockings are the chromatic key. Their violet pushes simultaneously toward red (echoing flesh) and toward blue (answering the green chair), so that they bind the scheme while commanding attention. Black—collar-like swath under the breasts, inner contours along thigh and torso, shoes—does structural work. It articulates planes the way a sculptor scores clay, turning color into volume without resorting to traditional modeling. Small zones of pale green in the face and hair cool the composition at the top, preventing the ochre ground from engulfing it.

Contour as Construction

Few twentieth-century painters use line as decisively as Matisse does here. The contour is not a timid outline but a load-bearing beam. It expands and contracts depending on the force it needs to exert. Around the shoulders and hips it thickens, almost calligraphic; across the stomach it thins, letting the plane breathe. In places the line seems to split, with a second, interior stroke doubling the first, the way a mason lays two courses of brick to strengthen a wall. This duality—line as drawing and as architecture—explains why the figure feels both flat and solid. The body occupies the surface and also convinces as a volume.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface is unvarnished and open. Ochre is dragged and scumbled so that the tooth of the canvas shows, giving the field a handmade vibration. The black passages are laid quickly, with a loaded brush that leaves ridges; their speed communicates certainty. Flesh is thinly painted, a chalky pink that refuses the buttery seduction of oil. Where the violet stockings meet the garter, paint puckers slightly, a tactile sign that color here marks not just hue but material and tension. The chair’s green reads as a single chord built from thin layers, its edges sometimes ragged—a reminder that the chair is a studio object, not a fetish of finish. The whole surface feels argued into being, not smoothed into decorum.

Space, Flatness, and the Stage of the Picture Plane

There is almost no conventional depth. The chair does not cast a shadow; the wall does not recede. Matisse wants the figure to inhabit the picture plane, not a fictive room. He achieves a convincing sense of sit-ness—of weight and contact—through overlaps and directional strokes rather than perspective. The thigh cuts across the seat ellipse; the back slat disappears behind the torso; the shoes flatten against the lower edge like punctuation. This stage-like space, with its frontal horizonless field, aligns the painting with the decorative ideal while keeping the human presence immediate.

The Stockings as Modern Gesture

Stockings in a nude are a charged detail. They do not “dress” the figure so much as declare her modern status—a model in a studio, a person in the present tense rather than in mythic time. They also divide the body into zones, just as the black abdominal band bisects the torso. The garters’ abrupt edge intensifies the sense of touch: fabric gripping skin, paint gripping canvas. Their violet, neither shy nor vulgar, sits halfway between flesh and chair, a chromatic mediator that becomes the painting’s signature. Without them the work would lose its bite; with them it declares its date.

The Chair as Spine and Counterform

Matisse’s green wicker chair appears often in this period, a portable architecture he can bend to each composition’s needs. Here it acts as the painting’s spine. The seat ellipse is the platform on which everything rests; the back’s verticals counter the figure’s curves; the green strands double the black contour, adding resilience to the outline. The chair also ensures that the painting belongs to a studio reality rather than to an invented Arcadia. It is the one object that maintains its identity against the pressure of stylization.

The Mask of the Face

The head is purposefully impersonal—no pupils, no individualizing detail—yet it exerts a powerful pull. Pale green runs across forehead and cheek like a wash of cool light; a darker wedge cuts along the jaw; black hair forms a compact cap. The presentation recalls Matisse’s attraction to the clarity of African and archaic sculpture: faces understood as essential planes rather than as lists of features. In the context of 1914, when anxiety and austerity shadowed European culture, the restraint feels ethical as well as formal. The model is not exposed to psychological probing; she is honored as a pictorial fact.

Body, Erotics, and Restraint

The nude’s frontal torso and assertive breasts announce sexuality, but the painting refuses theatrical eroticism. The stark divisions—the diagonal slash of thigh, the black bar under the breasts, the violet cylinders of stockings—abstract the body just enough to keep desire in check. What remains is a lucid acknowledgement of the body’s architecture and of the painter’s gaze as a structuring force. The work proposes that sensuality can coexist with discipline, that a figure can be tender and monumental at once.

Dialogue with Sculpture and Major Canvases

Looking from this canvas to Matisse’s “Back” reliefs or to “Bathers by a River,” one recognizes shared decisions: bodies simplified into tall, upright formats; heavy contours that read like grooves in stone; color used as a few resonant notes rather than as optical mixtures. “Seated Nude with Violet Stockings” compresses those sculptural lessons into an encounter on a chair. It is less ceremonial than the bathers and more raw than the Nice odalisques, a bridge between two poles of Matisse’s art—the architectonic and the decorative.

Relations to Cubism and Expressionism

Contemporaneous Cubism fractured volumes to explore multiplicity of view; German Expressionism intensified color and gesture to amplify emotion. Matisse takes a third path: he retains the figure’s wholeness, strips the setting, and lets contour and restricted color do the thinking. The black scaffolding might recall Expressionism’s harsh outlines, but the mood is not scream; it is resolution. Rather than deconstructing the body, he consolidates it. Modernity, in this account, is clarity rather than crisis.

Material Time and the Edge of War

The painting carries a compressed urgency that belongs to its date. Lines are decided, not fussed; surfaces are open, not glazed. It is easy to imagine the model posing in a brief, winter-bright session while the studio air holds its breath before history changes. The refusal of luxurious finish, the serialization of forms, and the fixed, sober gaze together suggest an artist who believes painting must be both exacting and swift—alive to the moment without being captive to it.

Anticipations and Aftermath

In the years immediately following, Matisse would relocate to Nice and cultivate a more languorous palette, staging odalisques amid patterned screens and Mediterranean light. Yet the strictness of “Seated Nude with Violet Stockings” remains folded inside those later works like a backbone. The Nice interiors may swathe the figure in textiles and filtered sun, but their clarity of contour and their reliance on a few anchoring hues owe much to this 1913–1914 crucible. The painting is therefore not an isolated experiment but a seed.

What the Painting Teaches About Looking

The canvas instructs the eye to measure relations rather than details: violet against ochre, green against pink, thick line against thin, curve against straight. It models a kind of attention applicable far beyond the studio—how to recognize structure beneath appearance, how to honor decisiveness over decoration. To sit with it is to learn how little is needed to make a body present and how much responsibility a single color or line can carry when chosen without hesitation.

Conclusion

“Seated Nude with Violet Stockings” is a manifesto in the guise of a studio nude. With a handful of colors, a scaffold of black contour, and a format that concentrates the eye, Matisse demonstrates how modern painting can honor the human figure while rejecting illusionistic space and narrative embellishment. The green chair steadies the design; the violet stockings electrify it; the ochre ground dignifies it; the mask-like face withdraws just enough to keep the figure emblematic rather than anecdotal. The painting is not an interlude between famous periods but a core statement: clarity as courage, restraint as intensity, and the body as an architecture of grace under pressure.