Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Quiet Figure in a Room of Color

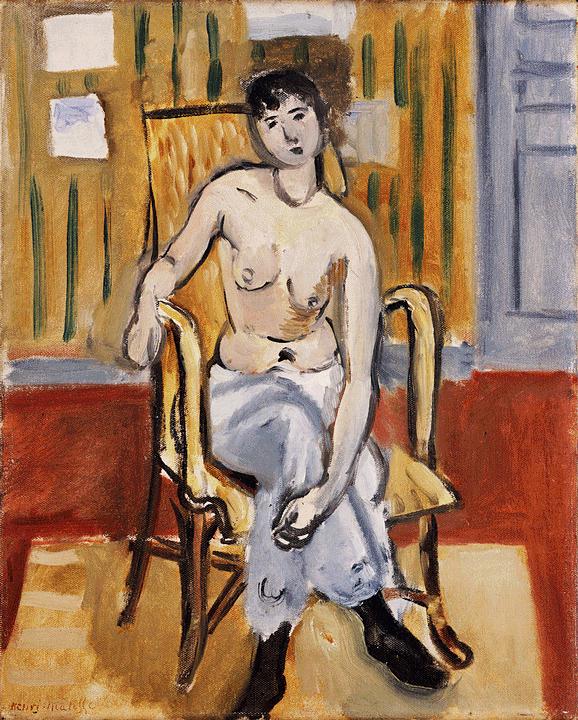

Henri Matisse’s “Seated Figure, Tan Room” offers a pared-down interior where a half-draped model settles into a bentwood chair. Her torso is turned toward us, one leg crossed over the other, the left hand falling loosely, the right arm resting on the chair’s curve. The space is simple yet charged: a tan wall marked by vertical green strokes, a red-oxide floor that glows like warm brick, and a cool blue rectangle at the right that reads as door or shutter. The chair’s honey yellow arcs bracket the body and echo the verticals behind. A soft white wrap pools around the sitter’s waist and thighs; a black shoe grounds the crossed leg. The painting reads at once—large shapes, tuned colors, and a few decisive black lines—but then rewards slower looking with adjustments of edge, temperature, and rhythm.

1918 and the New Key of the Nice Period

The date 1918 places the canvas at the threshold of Matisse’s Nice period, when he pivoted from the carved severity of the mid-1910s toward an art of climate, poise, and patterned air. Instead of shock color and jagged silhouette, he cultivated tuned chords, shallow but inhabitable rooms, and brushwork that keeps the time of its making. In this painting, the new key is unmistakable. Black is not outline but positive pigment. Pattern becomes structure. Light arrives as atmosphere rather than spotlight. And the human presence is quiet, contemporary, and dignified—no myth, no melodrama, only a person in a chair inside a room.

Composition: Chair Brackets, Central Column, and Flanking Fields

Matisse composes with three interlocking blocks. At center, the figure reads as a pale, vertical column, slightly tilted by the head’s cant and the crossed legs. On both sides, flanking fields stabilize the body: the tan-green wall at left and center, and the cooler blue panel at right. The bentwood chair works like golden parentheses around the sitter. Its arms sweep forward to catch the relaxed hands; its back rises behind the head like a haloed rectangle. Underfoot, the red floor spreads as a continuous plane that both supports the figure and warms the palette. Rectangles and arcs negotiate the eye’s passage: vertical wall marks, curved chair arms, the diagonal of the crossed shin, the soft trapezoid of the white wrap. Everything cooperates to keep the viewer’s attention moving, never snagged by detail.

The Pose: Casual Asymmetry and Inner Reserve

The sitting pose is resolved yet unforced. One shoulder slopes; the head tilts a degree to the left; the right wrist slackens over the chair arm; the left hand dangles in front of the crossed knee. Nothing is theatrical, and nothing is rigid. Casual asymmetry makes the figure legible as a living person rather than a demonstration of anatomy. The expression is withheld, inward. The model’s gaze lands just off to the side, consistent with Matisse’s ethical reserve during this period: attention without intrusion, presence without performance.

The Chair as Golden Scaffold

Matisse’s bentwood chair is a structural partner, not a prop. Its ochre arcs echo the wall’s vertical accents and the floor’s warm field, binding furniture to architecture. The chair’s geometry also solves spatial problems: its forward-thrust arms stage the forearms; its back sets the height of the head; its angled seat accepts the cross-leg without contortion. Because the chair is stated with confident strokes rather than fussy description, it remains a scaffold for the figure’s rhythm rather than a piece of inventory.

Palette: Tan, Green, Red, and a Cooling Blue

The color chord is balanced and economical. Tan dominates the wall but is interrupted by vertical green strokes, like simplified wallpaper reeds. The floor is a dense red-oxide that pushes warmth into the figure’s skin and the chair’s ochres. The blue field at right cools the composition and prevents the warm colors from pooling into heaviness. Flesh is a blend of peach, gray, and pale ochre, shifting cooler where planes turn away from the light—beneath the clavicle, under the breast, inside the elbow. The white wrap is not neutral; it modulates from warm near the torso to cooler at the knees, picking up reflections from the blue panel. Black accents—hair, eyes, shoe, and a few decisive seams—anchor the palette and carry drawing inside the color.

Black as Positive Color

No one uses black like Matisse. Here it is a living pigment that structures the room. The black shoe on the crossed foot weights the lower right and keeps the light wrap from floating. Thin, elastic blacks articulate eyelids and curls, the hinge under the breast, the inside contour of the forearm, and the seam where wrap meets thigh. The chair gains definition from a nibbed black drawn along its near arm. These darks warm or cool depending on neighbors—warming against the red floor, cooling near the blue panel—and they keep the airy palette in tune without closing it down.

Light as Climate Rather Than Spotlight

Light in the painting is a continuous atmosphere, not a single beam. The torso’s front plane is gently illuminated; transitions occur by temperature shift, not by hard shadow. The tan wall glows, catching room light and reflecting it forward. The floor carries a reddish sheen as if scrubbed. The blue panel absorbs light and returns it as a stable cool. Because illumination is treated as climate, the figure’s presence feels sustainable—you sense minutes passing, not a frozen instant.

Pattern and Mark as Architecture of Mood

What reads as wallpaper is really a pattern of vertical marks that functions architecturally. The green strokes break the tan field into a rhythm that keeps the wall active and upright. They also echo the sitter’s vertical axis and the chair’s uprights, enforcing posture without rigidity. On the floor, a paler rug field introduces a softer rectangle beneath the chair, a cushion of value that prevents the legs from sinking into the red. Pattern is never ornamental filler; it paces the image and gives the room its slow pulse.

Edges and Joins: How Forms Share Air

Edges in this picture act like seams in a garment. Along the shoulder, the flesh meets the wall with a breathed boundary that reads as air, not outline. The inner contour of the crossed leg is a quick, darker seam that brings the knee forward while keeping the wrap believable. The wrist resting on the chair arm is seated with a short, firmer edge so hand and wood do not fuse. The blue panel meets the wall with a softened join—just enough blur to suggest a reveal or depth in the doorframe. Each join is adjusted to keep the simplified shapes inside the same climate.

Brushwork: The Visible Pace of Making

The surface is candid about its construction. Tan wall strokes are laid vertically and left; greens are added in a second, more pigmented pass. The floor’s red is pulled horizontally with enough pressure to leave ridges and small flashes of ground. Flesh is built with medium-length, directional touches that follow bone and muscle. The white wrap is churned in two temperatures, warm and cool, to imply fold and weight. The chair’s ochre arcs are a few loaded curves, their insides sometimes catching a rim of black. This rhythm of decisions—clear, varied, unlabored—is part of the painting’s modernity.

Space Kept Close to the Plane

Matisse keeps depth shallow and convincing. Overlap does the main work: figure over chair, chair over rug, rug over floor, floor against wall, wall before blue panel. Value steps and temperature shifts finish the job. Because nothing plunges into deep perspective, the painting reads as designed surface and as room simultaneously. That closeness to the plane allows the color chord to function musically while the space remains habitable.

Anatomy Simplified, Presence Preserved

The figure’s anatomy is clarified to planes and inflections. The collarbone spans as a quick bridge; the sternum is a small vertical note; the breast is stated with one warm curve and one cooler shadow; the navel is a dot of dark set inside a slightly cooler oval. The knee is a swivel of warm and cool whites; the shin is a narrow column that turns with a single seam; the elbow is a bent wedge. These simplifications preserve presence without pedantry. The body is recognizable because relations are exact, not because details are multiplied.

Rhythm: Vertical Beats, Curved Phrases, and a Cross-Leg Cadence

The painting’s music arranges itself into three families. Vertical beats drum along the wall and inside the chair back. Curved phrases arc through the chair arms, the outline of the torso, and the u-shaped wrap. A cross-leg cadence accelerates the lower half: ankle, shin, knee, and dangling hand combine into a relaxed yet dynamic cluster. As the eye travels from face to hand to shoe and back, these rhythms interlock and keep the composition supple.

The Blue Panel as Counter-Field

The rectangle of blue at the right edge is a quiet masterstroke. It balances the red floor chromatically, cool against warm. It complicates the wall’s plane by introducing a perpendicular surface, hinting at a door opened to daylight or a shuttered window. It also frames the profile of the sitter’s head with a cool halo, making hair and features more legible. Without this blue, the picture would be all interior heat; with it, the room breathes.

A Room as Self-Portrait by Indirection

Like many Nice-period interiors, the painting doubles as a discreet self-portrait of the artist’s working life. The bentwood chair, the patterned wall, the small rug, the pale door or shutter, and the warm floor are workaday studio facts. But gathered and tuned, they say more about Matisse’s temperament than any literal depiction: he seeks calm through relation, clarity through simplification, intimacy through distance, and beauty through exact restraint.

Dialogues with Tradition, Rephrased

The seated nude in a room has a long history, yet Matisse rephrases the motif in modern terms. He refuses classical finish in favor of visible decision. He replaces theatrical chiaroscuro with temperature modeling. He lets pattern do architectural work where academic painters might build deep perspective. He grants the sitter privacy and the viewer companionship rather than invitation. The result is a picture that honors tradition without quotation.

Guided Close Looking: A Practical Circuit

Begin at the face. Notice the small darks that set the eyes beneath soft lids, the dipped corner of the mouth, the quick shadow under the chin. Slide down the clavicle to the sternum’s small note, then across the breast where a warm curve meets a cooler seam. Drop to the white wrap at the waist; feel how its warm highlights meet cooler shadows as it turns over the lap. Follow the crossed leg to the black shoe, a solid punctuation that prevents drift. Let the eye rise along the near chair arm, across the back’s ochre grid, and up the green strokes of the wall before returning to the tilted head. Each loop clarifies how few elements are needed to sustain the entire scene.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Look for small revisions left in place. The far forearm has a faint earlier line ghosting beneath the final contour. A darker notch at the waist reins in a once-wider wrap. The boundary between wall and blue panel is restated with a softer seam to reduce an initial hardness. These visible decisions are not blemishes; they are the record of arriving. Matisse halts when relations feel inevitable, not when surfaces are cosmetically uniform. That earned inevitability is the painting’s calm.

Lessons Embedded in the Canvas

This work functions as a compact manual for painters and designers. Black can be a living color that stabilizes light chords. Pattern can carry structure when perspective is kept near the plane. Light modeled by temperature is more breathable than light forged by heavy shadow. Edges are tools for seating forms in the same air. And a handful of exact relations—tan wall with green accents, red floor, blue panel, ochre chair, pale body—can replace narrative with presence.

Why the Picture Still Feels Contemporary

A century on, the image retains its freshness because it trusts essentials. Big shapes read at a glance. The palette is sophisticated but unstrained. Process remains visible and honest. The sitter’s privacy aligns with modern sensibilities, and the room’s design language parallels contemporary interiors: warm floor, neutral wall with graphic accents, a single cool plane to oxygenate the scheme. The painting is easy to live with because it invites the viewer’s breathing to match its measured pace.

Conclusion: Calm Achieved through Relation

“Seated Figure, Tan Room” distills a person and a place into a few necessary terms: a golden chair as bracket, a red floor as hearth, a tan wall as field, a blue panel as breath, and a body modeled by temperature and poised by asymmetry. With these means, Matisse composes a humane equilibrium—no spectacle, only a practiced serenity in which color, line, and air do the quiet work of keeping company. The painting offers what many seek from art and from rooms alike: clarity without coldness, warmth without noise, and a space where attention can rest.