Image source: wikiart.org

A Lively Still Life at the Edge of the Sea

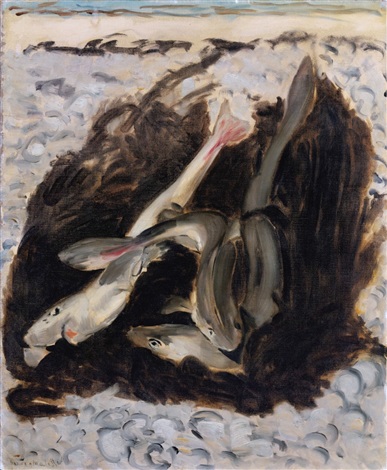

Henri Matisse’s “Sea Dogs” (1920) is a compact, energetic canvas that transforms a humble subject—several small dogfish—into a rhythmic drama of line, light, and motion. At first glance you might think you’re looking at a cluster of living forms caught in a whirl of surf; step closer and the painting resolves into a still life staged on the shore, the fish twisting over a dark patch like a tidepool carved into foam-streaked sand. The surprise of the picture lies in how it straddles categories. It is both a study of nature and an essay in pure pictorial orchestration, using a pared palette and sweeping, calligraphic brushwork to make the sea’s agitation palpable without ever literally depicting waves. Matisse takes an ordinary coastal motif and distills it into a visual tempo—quick, circling, almost musical—that has the taut clarity he sought after World War I.

The 1920 Moment and Matisse’s “Return to Order”

By 1920, Matisse had moved beyond the blazing Fauvist color of 1905–1908 and the densely patterned interiors of the 1910s. The war years and their aftermath led many European artists toward a “return to order,” emphasizing structure, legibility, and classical calm. For Matisse, this did not mean renouncing freedom; rather, it meant a new equilibrium between expressive gesture and disciplined drawing. His Nice period favored lucid light, simplified volumes, and compositions that read cleanly from across a room. “Sea Dogs,” painted early in that decade, embodies this balance. The forms are few, the palette restrained, yet the touch is as alive as ever. You sense an artist revisiting nature with fresh sobriety, interested not in spectacle but in the essential: how a form curves, how light skims a slick surface, how a dark void can anchor an entire field of scattered whites and greys.

What the Title Names: Dogfish, Not Dogs

The French phrase “chiens de mer” designates dogfish—small sharks commonly caught near the coast. Matisse’s title, rendered in English as “Sea Dogs,” may amuse the ear, but it is precise. These are fish lying where the tide meets the shore, their pale bellies catching light, their fins flushed with a pinkish note. The subject is unpretentious and local, the kind of thing a painter might have observed during a walk by the water. Yet Matisse refuses the picturesque. He gives us no horizon and no scenic context. By cropping tight and pressing the fish into a knotted cluster, he emphasizes their sinuous profiles and the way they echo one another, turning a casual sight into a study of repetition and variation.

The Architecture of the Image

Compositionally, the painting pivots on a dark, almost bean-shaped mass that occupies the central right portion of the canvas. It reads as a wet hollow in the sand, a pocket of pooled water, or even the shadowed underside of the catch. Against this sinkhole of tone, the fish flare into view as light forms bending across the void: two pitch diagonally upward, one curves back, another glides horizontally. Their bodies establish a sequence of S-curves, a choreography that carries the eye in a looping path around the center before dispersing into the stippled field of surf. This centrifugal arrangement—spiraling out from a dark core—gives the image tension and coherence. The corners remain light and airy, while the middle compresses; the whole picture breathes like a lung.

Color, Light, and the Discipline of Restraint

The palette is deliberately limited: chalky whites and soft greys for surf and sand; a near-black brown for the core shadow; muted ochres and umbers to warm edges; and sparing notes of coral-pink at mouths and fins. The overall effect is tonally cool, which suits the marine theme, but the few warm accents prevent chill. Matisse isn’t trying to “match” nature’s color so much as to state a harmony that feels inevitable. Notice how the pink of a fin appears only where the eye needs a lift, how the lightest whites cluster near the center, and how the greys break into small circular touches that evoke foam without describing it literally. Light here is not a single source but a general, pearly illumination gleaned from the sky and bounced off wet surfaces. The fish glisten because the surrounding field is matte and broken, making their smoother highlights pop.

Brushwork and the Calligraphy of Form

If you track Matisse’s brush, you can almost reconstruct his process. He seems to have scrubbed in the field of foamy sand with quick, circular, wet-on-wet marks, leaving small intervals of canvas that sparkle like aerated water. Over this he laid the dark heart of the composition in long, confident sweeps, dragging pigment so that it feathers along the edges. Finally he drew the fish with an economy of strokes that belies how convincing they are: a single pull for the spine, a pressure change to widen the belly, a decisive flick to close the mouth. Here and there he reinforces a contour with a darker line, but he often lets edges dissolve into the background, the classic “lost and found” treatment that gives life to an outline. The result is an image that looks spontaneous and controlled at once, as if tossed off in a burst and yet perfectly judged.

Depth, Movement, and the Energy of the Sea

Though the surface is shallow—no deep perspective, no panorama—Matisse conjures a surprising sense of movement. The foam marks are not random; they align in slanted clusters, like gusts of wind whipping across the water. The fish bodies, varying in angle and scale, shift the viewer’s sense of depth in micro-steps: one head thrusts forward, another recedes, a tail slices underneath. The dark cavity functions like a pivot point around which all other elements spin. In effect, Matisse compresses the sea’s ceaseless churn into a tabletop drama. The canvas behaves like the shoreline itself, where solid and liquid keep trading places, and where still life can turn kinetic because the setting refuses to hold still.

A Hybrid of Genre: Marine Painting Meets Still Life

Is “Sea Dogs” a marine piece or a still life? It is both. In conventional still life, objects rest on a table; here the “table” is a slice of littoral terrain. In conventional marine painting, the horizon and sky dominate; here they are absent, replaced by a close view of what the sea leaves behind. This hybridization allows Matisse to do two things at once: study the tactile presence of bodies and translate a landscape element into an abstract pattern. The foam field reads as a decorative ground, almost textile-like, while the fish retain the particularity of living creatures. The tension between pattern and specificity is a hallmark of Matisse’s art from the beginning, and here it is renewed in a salt-streaked idiom.

Touches of Naturalism, Hints of Abstraction

The fish are recognizable—snub-nosed, sleek, the dorsal fins short and blunt as befits dogfish—but Matisse refuses minute description. He gives just enough anatomy to satisfy recognition and then shifts attention to the larger orchestration of shapes. The dark pool is not modeled in detail; it is a single, resonant tone. The foam is not foam so much as a mosaic of ovals and commas. This oscillation between observed fact and pictorial invention allows the painting to be read on multiple levels. From a distance it vibrates as an arrangement of pale, buoyant forms against a single anchoring mass. Up close it yields small pleasures of touch: a sweep that suddenly thins, a wet edge that bleeds into grey, a pink accent that rides the crest of a curve. The discipline of leaving things out—of refusing illustrative excess—is what gives the work its modern bite.

Postwar Sensibility and the Poetics of the Ordinary

After a decade of upheaval, European artists often found poetry in ordinary subjects. “Sea Dogs” participates in this sensibility. There is no grand allegory here, but the image quietly touches themes of vulnerability and persistence. Fish pulled from the water lie poised between life and consumption; the sea that bore them presses near, rolling up in flecks and swirls. The painting thus registers a human world—the world of catching, cleaning, cooking—without depicting any people. Its drama is not tragic but elemental, a reminder that art can locate depth in the familiar. Matisse’s refusal to sentimentalize or moralize keeps the image open, capable of being read simply as a beautiful arrangement or, if one wishes, as a meditation on cycles of nature and appetite.

Conversations Within Matisse’s Own Work

Matisse painted and drew fish throughout his career, from aquaria glimpsed in studios to silver-scaled catches laid out on plates. “Sea Dogs” compresses that interest into one of his tightest, most graphic solutions. Compare it to an earlier Fauvist still life and you notice how the high-key chroma has been dialed back; compare it to later Nice interiors and you recognize the same love of economy and clear contour, but now harnessed to a rugged outdoor subject. The rounded foam shapes even anticipate the organic cut-outs of the 1940s, where repeated motifs—leaf, heart, teardrop—build rhythmic fields around a powerful void. In this small coastal canvas you can sense the seeds of those later abstractions, proof that Matisse’s experimentation with pattern was never confined to carpets and screens.

Material Presence and the Look of Oil Paint

The painting’s pleasures are inseparable from oil paint itself. Oil allows the thin, quick scrubbing of the ground and the buttery, opaque strokes of the fish to coexist without jarring. It accommodates the wet-in-wet blending at the foam edges and the crisp, dry touch that defines an eye or lip in a single mark. Matisse always used materials with finesse—choosing when to let the brush skate and when to press—and here he exploits the medium’s full dynamic range. The dark pool has weight, the whites sparkle, and the pink notes feel suspended on the surface like tiny flags. The facture is evident but never heavy; you read the hand without being distracted from the image.

The Logic of Simplification

One of Matisse’s guiding beliefs was that simplification leads to intensity. In “Sea Dogs,” simplification operates at every level: a narrow palette yields a strong tonal design; cropped forms create immediacy; minimal anatomical detail concentrates our gaze on silhouette and rhythm. Even the omission of the horizon is a simplification that heightens the picture’s impact, because it prevents us from relaxing into narrative. We are kept inside the painting’s closed system of curves and counter-curves, where every brushstroke helps sustain the central spiral. This is not simplification as emptiness; it is simplification as compression, the act of removing everything that does not contribute to the theme of motion around a dark core.

How to Look Closely at “Sea Dogs”

Begin by letting your eye fall on the darkest region and notice how it tethers the composition. Then track the longest fish from head to tail, feeling how its S-curve skims the pool’s rim before flicking outward. Jump to the small fish near the bottom; observe how its angle resists the others, like a syncopated beat that keeps the rhythm lively. Step back and let the foam read as a field of repeated marks; step closer and count the variations—some ovals closed, some open, some pressed so hard the brush left a ridge. Finally, return to the pinks. There are not many of them, and each is placed where it will pierce the surrounding grey. The painting rewards this oscillation between overview and detail because it was built on the same principle: large tonal forces animated by exact, quick touches.

Why the Picture Feels Fresh a Century Later

“Sea Dogs” feels surprisingly contemporary, not because of any shock value, but because it solves a perennial problem with serene confidence: how to make a convincing, engaging image with very little. Its energy comes from the negotiation between opposites—light and dark, curve and counter-curve, description and abstraction—rather than from narrative or novelty. Viewers used to the blunt brights of Fauvism sometimes underestimate Matisse’s quiet 1920s canvases; in truth, they are laboratories where he refined his syntax. The spare means and tactile presence of this work resonate with painters today who seek clarity without rigidity and gesture without chaos. It is a masterclass in how to let marks breathe, how to allow the eye to complete what the hand only suggests.

A Coastal Meditation in Paint

In the end, “Sea Dogs” is a meditation on the meeting of bodies and elements. The fish are solid but slippery, the ground is firm but saturated, the water is transient yet structuring. Matisse catches that hinge-moment when forms are most legible—right after the tide has pulled back, right before the next surge. The painting’s beauty lies in how that hinge becomes a visual principle: everything turns around a center, like tide around a rock or thought around a theme. There is no rhetoric here, no dramatic sky or heroic vessel. There is only a handful of fish, a dark pocket, and a field of marks that crystallize the sea’s ceaseless pulse. From these few parts Matisse builds a complete experience.