Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

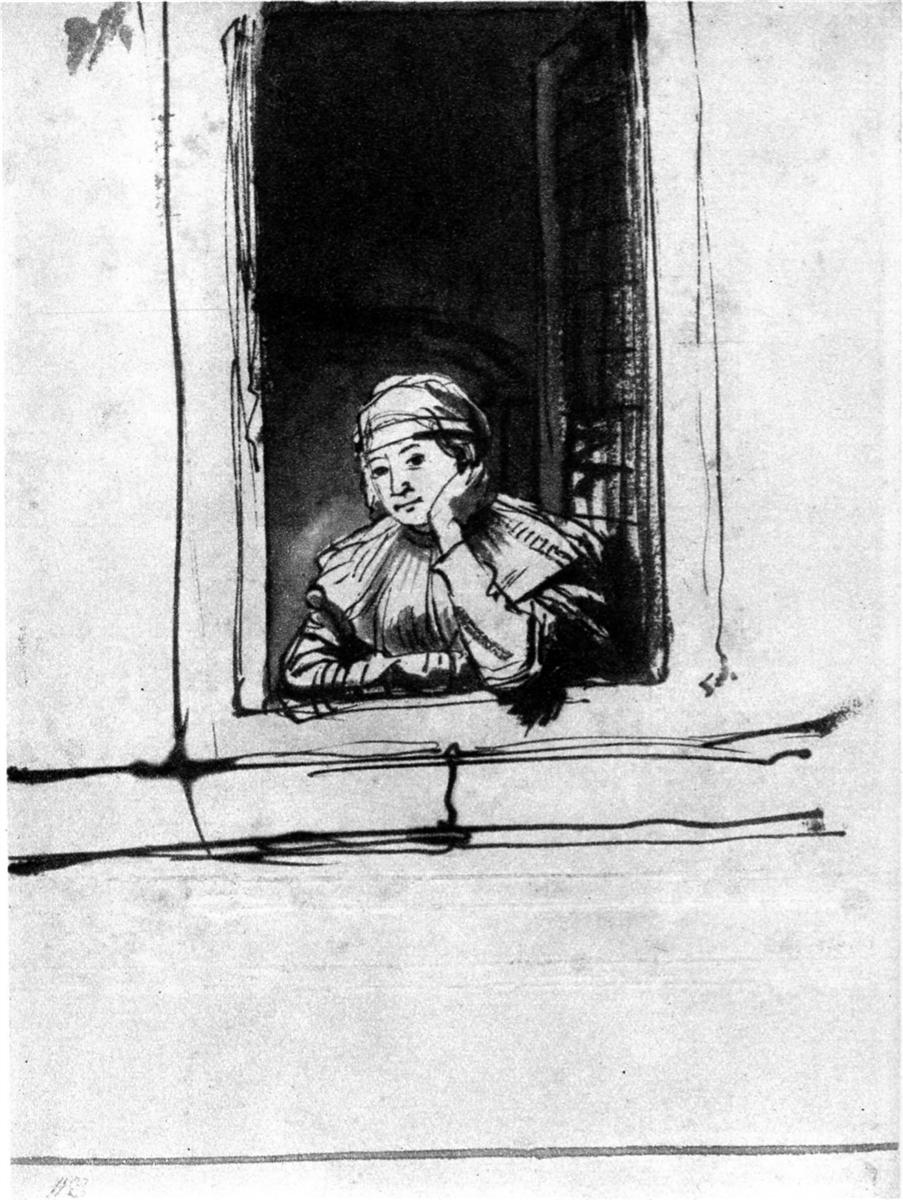

Rembrandt’s “Saskia Looking Out of a Window” (1635) is a quiet burst of intimacy. In a few urgent strokes of pen and a handful of smoky washes, he catches a young woman leaning on a sill, chin in hand, dawdling at the border between interior and street. The rectangle of the opening is a stage and a shelter; her small, thoughtful face glows against the surrounding dusk. This is no stiff allegory or public commission but a tender, observational drawing—swift, candid, and disarmingly modern. It compresses love, architecture, and light into a simple motif: a pause at a window.

Subject, year, and why it matters

The date matters because 1635 was the season when Rembrandt’s relationship with Saskia van Uylenburgh—the cousin of his art dealer and soon his wife—was blooming. He sketched her obsessively in these years, testing costumes, attitudes, and moments of ordinary life. In this sheet Saskia isn’t a goddess, a biblical queen, or an emblem of plenty; she’s a person at ease, caught in the kind of unguarded moment lovers notice and remember. The drawing is a chamber-sized companion to Rembrandt’s larger studio ambitions of the mid-1630s and proof that his most durable power was attention rather than pomp.

Composition: the architecture of a glance

The design is startlingly economical. A tall, almost doorlike aperture frames Saskia. The left jamb and lintel are evoked with two or three confident lines; the right side disappears into dark wash, suggesting a recess or a shutter. The sill runs horizontally across the sheet like a white stage apron with a few elastic, wobbling lines on top, as if the artist’s hand were vibrating with energy. Saskia is placed low and right inside this opening, forming a diagonal that runs from the upper left corner of the aperture down through her head and resting elbow to the lower right. This diagonal animates stillness; the eye enters, finds her face, and then tracks the gentle slope of her arm to the ledge where the scene breathes.

The language of line

Rembrandt’s pen lines have a conversational ease. He doesn’t “finish” the window; he suggests a world with controlled incompleteness. The outline of Saskia’s cap is set down with springy curves; the bridge of the nose is a tiny hook; the lips are only a couple of quick flicks; the collar gathers into knots of short hatch that imply soft fabric rather than diagram it. The sleeve swells in two or three bulges that persuade the eye of volume. Around the aperture, long, almost calligraphic strokes describe masonry with a music closer to handwriting than to blueprint. The whole sheet feels written rather than merely drawn—an affectionate note in ink.

Wash and the weather of the room

A few diluted passages of gray-black wash supply air and time. Rembrandt floats darkness inside the window, letting it pool behind Saskia’s shoulder to push her forward. A vertical band at the right edge suggests the inside wall or shutter; whispery washes in the lower register imply reflected daylight off the sill. These tonal pools keep the drawing from becoming a cartoon of lines; they stage the face as a warm, thinking point in a cool space. The spareness is the point: where a lesser hand would fuss over bricks and panes, Rembrandt uses wash to give us breath and hush.

Light that behaves like understanding

The light does not glare; it listens. Because the ground is largely untouched paper, the brightest thing is the sill, then Saskia’s cheek and cap. The effect is of daylight drifting in, catching skin and linen and fading into the corridor behind. That gentle hierarchy—paper white, then face, then wash—reads as a visual ethics. The drawing values the human presence first, the architecture second, and everything else only as much as it helps those two meet.

Gesture, mood, and the sound of quiet

Saskia’s posture is a chord of small, truthful notes: chin propped by a relaxed palm, fingers half-curled, other arm slung across the sill, shoulders loose, gaze lowered and slightly sideways. It’s the pose of someone who isn’t waiting for anything in particular; she’s thinking, or simply letting time happen. The expression is not a smile, not a frown—just a soft availability to whatever passes in the street below. Through this everyday gesture, Rembrandt gives us not an emblem, but an afternoon.

The window as motif and metaphor

Windows in art are double agents: they promise a view and set a limit. Here the motif does three jobs at once. First, it frames Saskia, making her glow in a shallow stage that disciplines the composition. Second, it nails the theme of thresholds—between private and public, between love’s interior and the world outside. Third, it literalizes looking. We look at Saskia looking out; Rembrandt looked at her looking out; the drawing becomes a triangle of gazes. The subject is observation itself, turned into affection.

Domestic Amsterdam and the life of thresholds

Seventeenth-century Amsterdam was a city of windows: shopfronts opening to the street, upper-story sills where residents leaned to gossip and watch, canals that mirrored faces back to their rooms. Rembrandt absorbed this culture of looking. The masonry here is generic, not architectural portraiture, but it summons the feel of a narrow lane, where a passerby might glance up and catch exactly this sight: a young woman in a cap, thoughtful, unhurried. The drawing honors those fleeting social exchanges that knit neighborhoods together.

A private likeness colliding with public art

Rembrandt often folded private life into public pictures by casting Saskia as mythic or biblical figures. This sheet works the other way: it keeps the public world out and invites us into the private. Because nothing encodes the scene as “History,” the drawing reads across centuries with no translation required. You don’t need to decode iconography to understand a human leaning on a sill, half lost in thought. The image, for all its seventeenth-century ink and cap, belongs to anyone who has paused at a window.

Speed, spontaneity, and the accuracy of love

The drawing looks fast because it probably was. The springy line, the opportunistic wash, the uncorrected “wrong” lines along the sill—everything suggests immediacy. But speed here isn’t carelessness; it’s a form of sincerity. Rembrandt knew Saskia’s features so well that he could afford abbreviation. What a slow, polished portrait might lose in freshness, this quick sheet preserves: the rhythm of the moment, the little tilt of the head, the not-quite-smile that looks like thought budded into feeling.

Comparison with related works

Placed beside Rembrandt’s etched “Saskia with a Flower” or the painting “Saskia as Flora,” this drawing reveals a complementary register. In those more formal works she is costumed, emblematic, luminous. Here she is uncostumed, local, human-scale. Together they form a portrait of a relationship: public celebration and private recognition. The window motif also echoes later masterpieces—think of the figure at the casement in “Girl at a Window”—where a person at a threshold becomes a theater of inwardness. This 1635 sheet is an early, crystalline instance of that idea.

The page as a room

The physical sheet of paper feels like part of the architecture. Rembrandt leaves broad breathing fields untouched; the margin is not an afterthought but a light wall around the dark aperture. You can almost hear the scratch of the quill where the long vertical at left ends bluntly and the line stutters, then recommits. Those traces of making—pressure variations, slight blots—costume the drawing with time. They feel like the equivalent of footsteps and a chair’s creak in a quiet room.

A study of edges

Edges do the heavy lifting. Saskia’s right contour dissolves into the wash behind; the left cheek is crisply edged against light. The cap’s rim crispness softens into hair rendered with a few curly dashes. The sill’s front edge is a parade of three or four overlapping lines, not quite parallel. Those “errors” are intention: they animate the inert stone and keep the eye alert. Rembrandt understands that accuracy is more than correct geometry; it is the capture of life’s small imprecisions.

Time held between inside and outside

There is narrative potential, but it is modest. Perhaps Saskia has paused at the window because a cart rattled by; perhaps she is waiting for Rembrandt to set down his pen so they can walk; perhaps she watches the studio’s street with the fond half-detachment of someone newly arrived in a big city. The drawing gives no answers and needs none. It offers a temporal state—idle attention—that is as universal as it is unremarkable. That’s its beauty.

Sound and silence in a monochrome world

Monochrome can be noisy or quiet. Here it’s quiet. The wash is the hush of a room shaded from midday; the white paper is daylight bouncing off plaster; the thin pen lines are the tiny noises of domesticity, the mouse-scratch of a quill echoing the soft scrape of a sleeve on stone. The silence is not empty; it’s expectant, the kind that makes us suddenly aware of our own breathing when we look too long.

The viewer’s position and the ethics of looking

Where are we, relative to Saskia? Down in the street, looking up. That angle matters because it transforms the scene from domestic snapshot to social exchange. We are strangers who happen to glance up and meet her resting gaze. Rembrandt, who surely drew from within the room or from memory, nonetheless composes as if we were outside. It’s a quiet acknowledgment that seeing can be a form of contact, even without words. The sheet models an ethics of looking: respectful distance, attentive regard.

Preservation of spontaneity and the aura of a first thought

Some drawings feel like scaffolds for later paintings; this one feels sufficient unto itself. It preserves what poets call a “first thought”—fresh, unlabored, full of the energy of inception. That doesn’t make it less crafted. It takes years of practice to risk an unfinished edge or to trust a wash to do the work of a hundred lines. The confidence to stop is part of the artistry.

The resonance today

Modern viewers often find the drawing startlingly contemporary. Its minimalism anticipates reportage sketches, street photography, even comic panels where a frame pops open on a private moment. More importantly, its feeling is familiar: the urban pause, the little lean into air, the mind wandering beyond the room. In an era saturated with polished images, this frank, quick notation feels honest and humane.

What it tells us about Rembrandt and Saskia

The sheet is a love letter disguised as observation. It shows a painter attentive to the everyday ways someone he loves occupies space and time. It shows Saskia not as a symbol but as a companionable presence. The survival of such drawings is a gift: we witness the couple’s life not only at their grand, costumed peaks but also in their quiet, window-lit hours. That balance—splendor and ordinariness—is one reason Rembrandt remains the most human of the Old Masters.

Conclusion

“Saskia Looking Out of a Window” is a small marvel: a rectangle of ink and wash that carries the weight of intimacy without sentimentality. With a few sure lines Rembrandt builds a room; with a few warm strokes he gives us a face; with a patch of paper he makes daylight. The window becomes an emblem of everything the drawing accomplishes—opening outward while keeping a tender interior intact. To stand before it is to feel a breeze from 1635 move across your own present tense, and to hear, in the smallest possible voice, how love sees.