Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

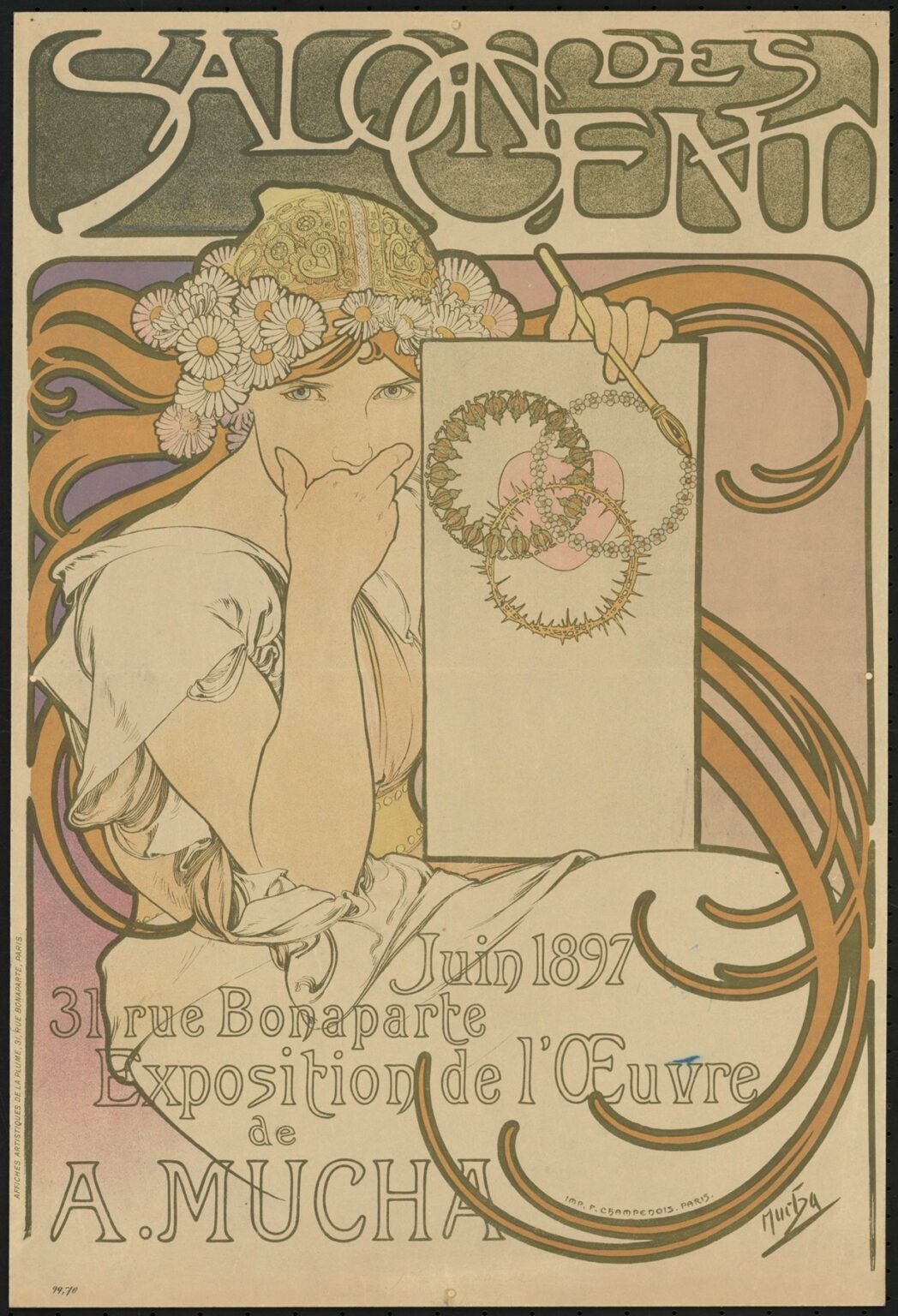

Alphonse Mucha’s 1897 poster “Salon des Cent. A. Mucha” is both a public announcement and a self-portrait of the artist’s method. Designed to advertise Mucha’s one-man exhibition at the Salon des Cent in June 1897, the sheet condenses the signature features that made him synonymous with Art Nouveau: a lyrical female figure, calligraphic hair that doubles as ornament, supple typography that seems drawn with the same pen as the picture, and an exquisitely choreographed page where negative space is as eloquent as ink. At a glance the poster reads clearly on the street; up close it unfolds a slow drama about looking, making, and the moment before revelation.

The Salon des Cent and Why This Poster Matters

The Salon des Cent—organized by the literary review La Plume—was a progressive, commercial exhibition devoted to original prints and drawings. It provided artists with a marketplace independent of the official Salon and catered to a growing middle-class audience that collected portfolios and posters for the home. By 1897 Mucha was already a star, thanks to his theater sheets for Sarah Bernhardt and his calendar-like allegories. A dedicated Salon des Cent exhibition of “l’œuvre de A. Mucha” was a way to consolidate that fame, and this poster had to sell both an event and a viewpoint: posters are not throwaway publicity but modern art one can own.

Composition as a Stage for Introspection

Mucha stages the action as a compact triangle of head, shoulder, and hand set against a large, pale rectangle: a painter’s board that the model lifts like a shield. The rectangle behaves like a stage curtain, giving the composition a foreground plane without using traditional perspective. It also provides space to quote Mucha’s own motifs—three interlacing floral garlands—so that the poster becomes meta-poster: a picture about pictures. Behind the figure a band of lavender and peach arcs like a proscenium, while the top is capped by a dark olive title block. The result is both stable and fluid; every curve has a counter-curve, every mass a quiet partner.

The Enigmatic Model and the Gesture of Secrecy

Unlike the dreamers who populate Mucha’s earlier Salon des Cent sheets, this woman looks directly at us. Her eyes are calm but alert; her right hand grazes her lips in a gesture that reads as a playful “hush.” That single sign turns the poster into narrative. She knows something—the content of the show, the trick of the studio—and we are invited to come find out. The gesture also links seeing and speaking: Art is what happens right before you break the silence. Few posters ask the viewer to lean in; this one does, and that intimacy is its most persuasive tool.

Crown of Daisies, Cap of Craft

Around her head runs a coronet of daisies, a flower long associated with freshness and candor. Set behind it is a small embroidered cap, the sort of artisanal headgear that suggests the workshop rather than the stage. Together they fuse innocence and mastery, a smart emblem for an exhibition meant to show that commercial illustration could be both popular and finely made. The daisies also become a miniature laboratory for Mucha’s line: each petal a clean arc, each disk a warm dot, building complex texture from very simple parts.

The Painter’s Board and the Three Garlands

The vertical board she holds displays three interlocking rings of small blossoms. At poster distance they read as a decorative knot; up close they look like the “wreath-halos” that Mucha loved to place behind his heroines, now abstracted into pure modules. It is hard not to read the trio as a manifesto of method: the artist’s vocabulary is a limited set of simple, repeatable units that can be overlapped, scaled, and recombined to generate endless variety. The triple interlace also nods to cyclical time—seasons, months, zodiac—recurring themes in his calendars and portfolios. By putting this grammar on the painter’s board, Mucha shows his working without demystifying the spell.

Hair as Ornament and Architecture

From behind the panel, the model’s hair surges outward in long, rivulet-like ribbons that spiral into the lower right corner and loop back under the text. In Mucha, hair is never mere description; it is architecture. Here it does at least three jobs. It frames the face; it knits picture and lettering into one field; and it provides the tempo of the page, a rising and falling rhythm that the eye follows in slow arcs. The thick key line keeps the curls crisp for street reading, while interior openings—small lakes of paper showing through—prevent the dark mass from feeling heavy.

A Palette Tuned to Whisper

The colors are restrained and edible: toasted creams for skin and paper, olive and moss for the title block, pale mauve and apricot-peach for the bands and shadows, honey-brown for hair, and tiny bursts of yellow at the daisy centers. Nothing shouts. Even the headline SALON DES CENT is filled with a soft, stippled green. This hush is tactical. The poster lives in the same tonal family as the parchment pages and matte walls of the cafés and bookstores where it would be posted, so it feels at home even as it announces something new.

Typography that Breathes the Same Air

Mucha’s hand-drawn letters are inseparable from the image. SALON DES CENT at the top is a tapestry of swelling strokes and rounded counters that echo the hair’s organic pattern. In the lower half, the informational text—“Juin 1897, 31 rue Bonaparte, Exposition de l’Œuvre de A. Mucha”—is written in a narrower, more legible register but still with the same flexible tool. The descenders and curves thread through the hair ribbons as if letters and locks were composed together. Advertising becomes one continuous drawing, and the usual hierarchy of “image above, type below” dissolves into unity.

Printing Intelligence and the Craft of Chromolithography

The poster’s easy grace rests on hard technical choices. It is engineered for chromolithography: flat color shapes that register neatly under a strong key line, transparent inks that create gentle gradients without moiré, and enough unprinted paper to keep the sheet bright and affordable. The speckled fill in the top cartouche is more than a style; it disguises small variations in ink lay-down and gives the heavy band a textured life. The veil of color around the board’s edges keeps the rectangle from looking cut-and-paste while preserving its visual function as a stage.

The Title Block as Visual Anchor

That top block is a masterstroke. It handles three problems at once. It gives the poster a headline that can be read at a distance; it provides the necessary weight to balance the airy lower half; and it creates a ceiling against which the hair and the painter’s board can push. Without it, the composition might float. With it, the image has the architecture of a façade: pediment, frieze, and figure.

Between Publicity and Self-Portrait

Although no likeness is intended, the sheet is a portrait of Mucha’s artistic identity. The daisies name his fresh, accessible style; the cap stands for craft; the board displays his modular ornaments; the hair declares his calligraphic line; the hush gesture asserts the private spark that precedes a drawing. Even the address, 31, rue Bonaparte, situates him within the Left Bank’s web of publishers and printers who made Paris the capital of poster art. The poster says: come meet the method, not just the man.

Dialogue with the 1896 Salon des Cent Poster

Placed beside his 1896 “XXme Exposition du Salon des Cent,” the 1897 design looks cleaner and more analytical. The earlier sheet is all dream—eyes closed, veil drifting, stars exhaled toward a brush. Here the eyes are open, the hand holds a tool, and the compositional engine is a square board that organizes the page. The two images read as consecutive steps in a creative cycle: reverie and then articulation. For a returning audience, the difference signaled growth; the artist who charmed Paris in 1896 now showed the construction kit behind the charm.

The Viewer’s Journey Across the Page

Eye-tracking this poster reveals how carefully Mucha plans attention. We start in the top left at the large title, drop to the model’s gaze, slide along the finger-to-lip gesture, and meet the white rectangle that interrupts the body. The brush at the top right corner of the board makes a tiny arrow that points into the center where the three wreaths overlap; from there the hair’s arcs carry us to the lower right where the signature sits like a cadence. The information copy can be read at any point without breaking the flow. It is a page you don’t so much scan as drift across.

Symbolism without Pedantry

Mucha rarely loads a poster with fixed meanings; he prefers suggestive symbols that work at multiple levels. Daisies can be innocence or just summer. Three interlinked rings can be the grammar of design, a nod to cyclical time, or simply a pleasing geometry. The hush gesture can be secrecy, concentration, or flirtation. Because no single reading is enforced, the poster remains fresh on repeated viewing—an essential quality for a sheet that might hang for weeks in a bookstore window.

A Business Card for a New Kind of Artist

In 1897 the line between commercial work and high art was fiercely debated. Mucha’s poster quietly erases it. This is an advertisement, yes, but also a manifesto in which the artist shows his hand and claims the page as a site of personal style. The Salon des Cent understood the modern audience: people wanted images that improved daily life, that could be framed, saved, and lived with. “Salon des Cent. A. Mucha” operates as a large, beautiful business card for that idea.

Influence and Afterlives

The poster’s intertwining of type, hair, and modular ornament proved enormously influential. Designers borrowed the floating rectangles, the swelling letters, and the deliberate hush of the central gesture. Later waves—from Jugendstil in Germany to the psychedelic posters of the 1960s—replayed its formulas of line and halo, sometimes knowingly, sometimes because Mucha’s language had become the shared DNA of decorative graphics. For contemporary branding, the sheet remains a primer in how to sell atmosphere and authorship rather than just logistics.

Why the Image Still Works

The poster endures because it is economical and generous at once. There are only a handful of colors, a few strong shapes, and one memorable gesture, but the arrangement invites the eye to linger. It respects the viewer’s intelligence; it leaves space for breathing and interpretation. It also offers something rare in advertising: humility. The model does not demand attention; she withholds a bit and asks us to approach. That invitation—quiet, confident, and beautifully drawn—is very hard to refuse.

Conclusion

“Salon des Cent. A. Mucha” is more than an announcement for a June 1897 exhibition. It is a distilled statement of what made Mucha the emblem of Art Nouveau: rhythmic line, humane ornament, integrated typography, and a belief that everyday printed objects can carry poetry. The poster shows the artist as artisan and magician, revealing just enough of the trick to make the wonder stronger. Over a century later, its curves still guide the eye, its colors still calm the room, and its hush still promises that something worth seeing waits just beyond the edge of the page.