Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

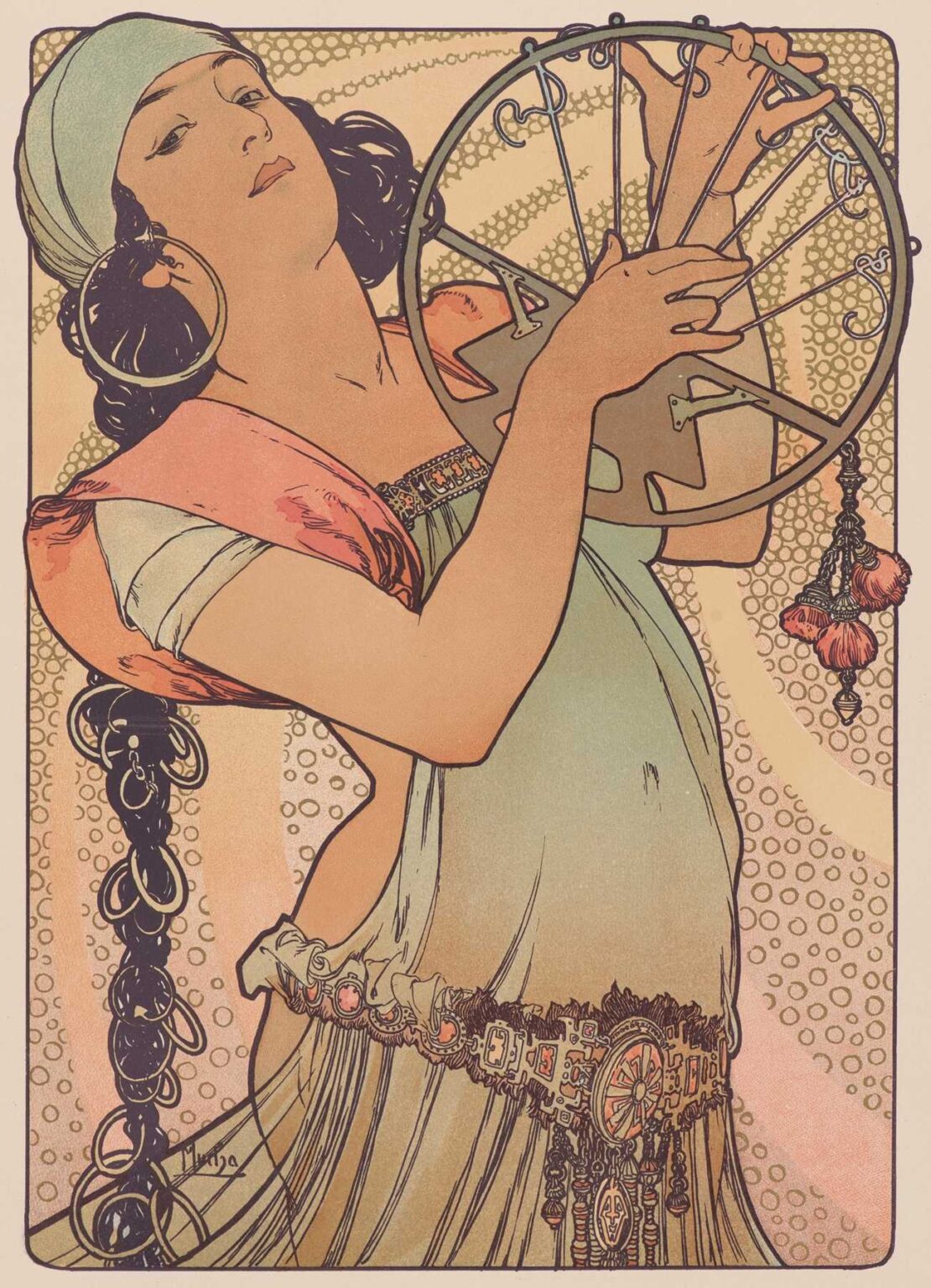

Alphonse Mucha’s 1897 lithograph Salomé represents a defining moment in the evolution of Art Nouveau and graphic poster design. Commissioned to advertise the era’s fascination with the Biblical figure of Salomé—famed for her Dance of the Seven Veils and the beheading of John the Baptist—Mucha’s portrayal transcends mere illustration. With sinuous linework, stylized ornament, and a muted yet rich color palette, he transforms a theatrical subject into a symbol of modern elegance and psychological intrigue. This analysis delves into the historical context, Mucha’s stylistic development, compositional strategies, iconographic depth, color and lighting techniques, decorative vocabulary, typographic considerations, technical lithographic process, contemporary reception, and enduring influence of Salomé.

Historical and Cultural Context

The late 1890s in Paris witnessed a surge of interest in Orientalist and biblical themes on stage and in visual arts. Sarah Bernhardt’s acclaimed performances of Oscar Wilde’s play Salomé in 1896–97 sparked public fascination with the enigmatic heroine. The press, posters, and program covers became battlegrounds for artists vying to capture her sensual mystique. At the same time, Art Nouveau emerged as a reaction against academic historicism, blending organic forms with modern design. Mucha, having revolutionized theatrical posters with his Gismonda sheet for Bernhardt two years earlier, was uniquely positioned to shape the visual identity of Salomé. His lithograph appeared amid a cultural landscape eager for images that fused exotic narrative with contemporary decorative flair.

Mucha’s Stylistic Evolution by 1897

By the time he undertook Salomé, Mucha had honed his signature style: elongated female figures, ornate floral halos, flowing drapery, and custom lettering. His training at the Académie Julian and early work as a magazine illustrator equipped him with precise draftsmanship, while exposure to Japanese woodblock prints inspired flattened planes of color and bold outlines. The success of his theater posters in 1894–1896 allowed him to refine his lithographic technique—mastering multi‐stone printing and experimenting with metallic inks. Salomé reflects this mature phase: the figure’s anatomy is more naturalistic than in his earliest works, the ornamentation is both abundant and controlled, and the palette is richer yet subtle. Mucha channels the drama of the stage into a still, jewel‐like composition.

Commission and Purpose

The Salomé lithograph served dual purposes: it advertised Bernhardt’s revival of Wilde’s play and demonstrated the printing prowess of Ferdinand Champenois’s workshop. Rather than depicting a literal scene, Mucha chose to evoke Salomé’s emotional aura—her calculated seduction and inner turmoil. The poster’s placement in theaters, cafés, and newspaper displays positioned it both as marketing collateral and as autonomous graphic art. Champenois benefited from the sheet’s decorative appeal, selling it as a portfolio print in stationery shops. Thus, Salomé straddles commercial function and aesthetic ambition, capturing the public imagination while showcasing Art Nouveau’s capacity to elevate advertising to fine art.

Subject Matter and Iconography

Mucha’s Salomé is not a simple narrative illustration; it is an allegorical portrait of the heroine’s complex persona. She stands in three‐quarter profile, her head turned in a suggestive glance that communicates both allure and danger. The wreath of lilies de mer—symbolic of purity—and red roses—symbolic of passion—adorns her coiffure, suggesting the paradox of innocence and seduction. Her fingers, elongated and poised, hold a stylized wheel or platter bearing the letters “Salomé” in Mucha’s distinctive type. This object may allude to the severed head of John the Baptist or to Salomé’s dance as a circular rite. By abstracting these elements, Mucha invites viewers to project their own interpretations onto the figure, blending mythic resonance with modern symbolism.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Mucha arranges Salomé within a roughly oval cartouche, itself set against a neutral background that allows the figure and ornament to command attention. The composition follows a gentle S‐curve: Salomé’s neck and torso lean back, her drapery cascades forward, and her hair flows in rhythmic arcs. This dynamic posture energizes the otherwise static format of a poster. The oval frame unites figure and decorative motifs, while its calligraphic outline echoes the sinuous lines of the hair and drapery. Negative space around the upper shoulders and below the drapery provides visual relief, ensuring that the image remains legible from a distance. Mucha balances these elements to create a composition both harmonious and subtly unsettling, reflecting Salomé’s dual nature.

Color Palette and Light Effects

Mucha’s palette for Salomé is at once lush and restrained. The background is a warm ivory, allowing other hues to glow. Salomé’s skin is rendered in pale peach, contrasted by the deep ebony of her hair. Her drapery incorporates soft greens and grays, while the floral wreath introduces accents of crimson and cream. Metallic bronze ink outlines key ornamental details—the oval frame, hair loops, and floral motifs—catching ambient light in evening street postings. Mucha layered translucent lithographic inks in successive passes, achieving subtle transitions between shadow and highlight. The overall effect evokes the flicker of stage lamps and the sheen of silk, reinforcing the theatrical subject.

Line Work and Decorative Motifs

Central to Mucha’s Art Nouveau vocabulary is the continuous “whiplash” line, and Salomé exemplifies its use. Hair strands, drapery folds, and floral stems all flow in unbroken curves that intersect and diverge across the composition. The decorative motifs—stylized water lilies, scrolling vines, and concentric halos—are integrated organically, never forming a distracting border but rather becoming part of the pictorial narrative. Mucha varies line weight to establish hierarchy: thick outlines emphasize the figure’s silhouette, medium strokes define floral and ornamental forms, and thin lines articulate fine details in hair and fabric textures. This orchestration of line unites subject and decoration in a seamless visual rhythm.

Typography and Lettering

Mucha’s custom lettering for Salomé appears in the circular object she holds—a wheel or platter—bearing the heroine’s name in stylized serifs. Each letter is carefully drawn to fit within the curved segments, echoing the circular frame. The choice to embed the title within the image rather than in a separate panel reinforces the poster’s integrated design philosophy. Mucha believed text should be a natural extension of imagery, and here the letters become decorative elements themselves, participating in the composition’s overall flow.

Technical Lithographic Process

Creating Salomé required meticulous collaboration between Mucha and the Champenois printery. Mucha first executed a full‐scale watercolor and pencil study, delineating color areas and line work. This study was transferred onto multiple limestone plates—each responsible for one color or ink—for eight to ten separate printing passes. Printers used registration marks to align the curved and flowing forms precisely. Translucent inks allowed the warm base paper tone to function as natural highlight, reducing the need for opaque white. Metallic bronze ink was applied in a final pass to accentuate lines and give the print a subtle gleam. The resulting lithograph married artisanal warmth with the crisp delineation possible through mechanical reproduction.

Reception and Contemporary Impact

Upon its release, Mucha’s Salomé lithograph generated buzz in both theatrical and artistic circles. Newspaper reviews noted the poster’s “haunting beauty” and its departure from literal scene depiction to emotional portraiture. Salon exhibitions featured the sheet alongside other Art Nouveau works, attracting collectors eager for decorative lithographs. Private buyers displayed Salomé in salons as proof of modern taste, while café‐goers admired its beauty on café walls. The poster’s success further solidified Mucha’s reputation and inspired his contemporaries—Georges de Feure, Eugène Grasset, and international designers—to explore similar fusions of figure and ornament.

Influence on Graphic Design and Beyond

Mucha’s Salomé contributed to the broader dissemination of Art Nouveau principles across Europe and North America. Its seamless integration of typography, decorative motifs, and figure influenced poster art in Germany’s Jugendstil, Britain’s Arts and Crafts movement, and the Vienna Secession. Print designers incorporated Mucha‐style letterforms into magazines and bookplates; interior decorators adapted his floral patterns for stencils and textile prints; jewelers translated circular frames and organic lines into necklace and brooch designs. The poster’s emphasis on psychological mood and elegant form anticipated modern illustration’s focus on atmosphere and stylization.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

More than a century after its creation, Mucha’s Salomé remains a touchstone of graphic poster art. Original lithographs are housed in institutions such as the Musée d’Orsay, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Victoria & Albert Museum. Conservation efforts preserve their delicate paper and shimmering inks, while digital reproductions introduce Mucha’s vision to new audiences. Graphic design curricula study Salomé as a prime example of integrated composition, custom typography, and emotional resonance. Contemporary artists and designers continue to draw inspiration from its harmonious curves, floral symbolism, and the boldness of its theatrical allegory.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Salomé stands as a masterful interplay of art, commerce, and narrative. Through sinuous linework, a refined pastel palette, and emblematic ornament, Mucha transcends the conventions of theatrical advertising, offering instead a portrait of mythic allure and psychological depth. The lithograph’s technical brilliance and harmonious design cement its place as a cornerstone of Art Nouveau and graphic history. More than a century later, Salomé continues to captivate viewers with its timeless elegance and the radiant mystery of its heroine.