Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

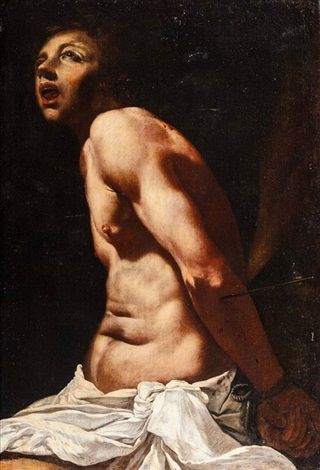

Caravaggio’s “Saint Sebastian” presents the Roman martyr with a closeness that feels almost unbearable. The young man is half-turned in a tight, vertical composition; his arms are bound behind him; a single arrow darkens the flesh of his side; a white cloth, tied hastily at the hips, gathers into a knot that both covers and emphasizes his vulnerability. Illumination presses hard from the left, carving the torso into planes of light and blood-warm shadow, while the background collapses into darkness. No architecture, no crowd of archers, no angelic consolation interrupts the scene. Caravaggio builds everything from body, light, and breath, and the result is a portrait of martyrdom as a human event rather than a public spectacle.

The Legend and Why It Matters Here

Sebastian, an officer in the imperial guard and a Christian in secret, was condemned to death for his faith and shot with arrows. Popular imagery often shows him pierced repeatedly and transformed into a kind of living pin-cushion. Caravaggio chooses the opposite approach. Instead of multiplying wounds, he concentrates on one. He shows Sebastian not as an emblem of endurance but as a man caught at the instant when pain and revelation touch. The face tilts upward, mouth parted; the body tightens in the cords; the small arrow becomes enough to carry the whole story. By withholding the usual historical set pieces, the artist emphasizes the decisive interior moment: this is what it looks like when a human being holds on to a truth while violence closes in.

Composition and the Architecture of the Body

The composition is anchored by a powerful diagonal that runs from the head at upper left down through the arched back to the bound wrist at lower right. This diagonal is set against the vertical of the torso, a muscular column interrupted by the knot of the cloth and the dark stripe of the arrow. The eye reads the forms as a sentence: cry, chest, cord. Because the setting is nearly absent, anatomy becomes architecture. The ribcage makes a vaulted nave; the shoulder is a buttress; the turned abdomen marks the shift from one bay to the next. Caravaggio uses this architecture to funnel emotion. The viewer cannot drift; the figure keeps the gaze captive, returning it always to the line where life is threatened and affirmed at once.

Tenebrism as Moral Stagecraft

Light in this painting is a moral actor. It strikes forehead, cheek, clavicle, and the taut band of the biceps, then falls over the belly and ignites the knot of cloth before sliding into darkness along the thigh. The beam refuses the space behind Sebastian; it has come only for him. This is typical of Caravaggio’s tenebrism, which selects rather than floods. The drama is not theatrical blaze but surgical attention. Shadows are not emptiness; they are the world withdrawn so that the viewer and the saint can meet without distraction. Even the arrow reads like a line of shadow rather than a glittering object, denying spectacle in favor of fact.

The Face and the Grammar of Breath

Sebastian’s expression is the painting’s hinge. The parted lips register breath caught between cry and prayer. The head is lifted but not thrown back; the eyes seem to search the dark. Caravaggio avoids ecstatic trance and sentimental suffering. He records the difficult poise between pain and vision, the second when the body tells the truth of harm while the soul refuses collapse. This discipline of expression is central to the painter’s realism. He trusts that viewers will feel more when given less, and he understands that a single well-observed face can carry more spiritual weight than a crowd of angels.

Flesh as Landscape of Revelation

Caravaggio models flesh with a candor that marries anatomy to theology. The shoulder’s round catches a hard highlight; the sternum climbs like a ridge; the abdomen turns with a soft torque that makes the arrow’s penetration more acutely felt. The paint never prettifies. It records the faint marbling of skin, the warm transitions from light to shadow, the small tension at the corner of the mouth. In this honesty, the body becomes the site of revelation. The saint’s sanctity is not abstract; it is written in muscle and breath at the very point where a weapon has found purchase.

The Arrow and the Ethics of Restraint

Caravaggio places one arrow, not many. Its smallness is startling given the subject’s iconographic tradition. But the restraint is strategic. A single wound becomes legible. The viewer has the space to contemplate what a puncture means—the entry of a foreign object into living tissue, the shock of the first pain, the onset of bleeding. The moral rhetoric of the picture trusts that a single true detail is stronger than accumulation. By refusing gore, the painter honors both the saint and the viewer. He lays the burden of interpretation not on sensation but on recognition.

The White Cloth and the Poetics of Modesty

The cloth at the hips is more than cover; it is a rhetorical device. Its whiteness catches the same light that sculpts the torso, linking purity and exposure. The knot gathers the fabric into a sturdy shape that anchors the composition, a bright counterweight to the darker mass of the upper body. At a symbolic level, the cloth recalls baptismal linen and shroud, folding initiation and death into a single gesture. Caravaggio’s drapery never floats; it has weight. Here, that weight reads as the stubborn dignity of a man whose body remains his own even when bound.

Cords, Hands, and the Language of Bondage

Sebastian’s right wrist is tied behind him, the fingers half-curled into a suppressed reflex. Caravaggio often writes meaning with hands—open palms for blessing, splayed fingers for shock, a knuckle pressed against a tabletop for certainty. Here the bound hand is a clause in the picture’s grammar: action denied, self-possession maintained. The cords themselves are not decorative loops but blunt evidence. Their rough texture catches the light just enough to be read. They do not sensationalize restraint; they state it.

Space, Depth, and the Viewer’s Entry

The stage is shallow. A rough vertical at the far right hints at a post or tree, but the rest is a soft, enveloping dark. This compression pulls the viewer close. There is no corridor of space for neutrality. You stand, in effect, next to the young man. Caravaggio’s great insight was that sacred drama grows more persuasive as it grows more intimate. By eliminating architecture and audience, he converts the martyrdom from public theater into a private meeting, asking each viewer to decide what kind of witness they will be.

Dialogue with Earlier Images of Sebastian

From Mantegna to the High Renaissance, Sebastian often appears as a pale, smooth figure pierced with a flurry of arrows, bound to classical columns or tree trunks in bright landscapes. Caravaggio reimagines the type by darkening the stage, limiting the wounds, and intensifying the sense of breath. He keeps the erotic charge—Sebastian has long been a figure in whom beauty and suffering mingle—but he refuses the decorative distance in which pain can be admired. His Sebastian is not a statue; he is a person. The transformation sets the pattern for Baroque treatments that make the saint a psychologically convincing presence rather than a decorative emblem.

The Tension of the Sacred and Sensual

Caravaggio, more than perhaps any other painter of his time, understood that the sacred lives in bodies. The painting acknowledges the sensual appeal of the young male form—the smooth chest, the ascending line of the neck, the flushed lips—and it places that appeal in tension with humiliation and harm. The result is not titillation but complication. Sebastian’s beauty intensifies the moral stakes: violence against such a body is both injustice and sacrifice. The painter allows the viewer to feel desire, sorrow, and reverence without resolving them into a single emotion, which is why the picture continues to unsettle and to move.

Color and the Economy of Means

The palette is deliberately limited to warm flesh, black-brown ground, and the cool white of the cloth. This economy heightens the drama by refusing ornament. A single patch of reflected light in the background or a warm glint along the arrow’s shaft becomes eloquent because the painting has taught the eye to read small events. Caravaggio’s late manner often works this way: pared-down color elevates structure, gesture, and light to primary language.

Technique, Brushwork, and Surface

The surface reveals the painter’s confidence. Broad shadows are laid thinly so the ground breathes through; lit passages build up with denser paint that can hold shape under the dramatic beam. The transitions through half-tones on the torso are exquisitely judged, neither over-smoothed nor crude. Highlights on the shoulder and along the ridge of the ribs are placed with a surgeon’s certainty. The white cloth is handled with swift, ridged strokes that turn paint into fabric. There is no display for its own sake; every decision serves the illusion of a body at risk in a dark room.

Theological Resonances

Sebastian’s upward tilt has often been read as prayer at the edge of death. Caravaggio refuses the literal angel or the distant vision, but his beam of light implies visitation. In Christian terms the martyr shares Christ’s passion; here that sharing is signaled not by narrative details but by the way light dignifies wounded flesh. The painting suggests that grace is not an escape from pain; it is a way of being present to it. The single arrow becomes a sign of participation rather than defeat.

Psychology of Pain and Courage

Pain in most pictures is either minimized or melodramatic. Caravaggio aims for truth. The mouth is open enough to suggest breath taken sharply; the abdomen tightens; the muscles around the shoulder assert themselves. But the face also shows control. The gaze is not shattered; it is lifted. Courage appears as attention rather than bravado, as a willingness to keep looking even when the body demands retreat. This psychology feels startlingly modern. It honors both the sensory fact and the moral choice.

The Role of Time

The painting captures a precise second—after the strike, before collapse. That suspended moment lets viewers inhabit a liminal zone where significance becomes legible. We are not in the chaos of action or the stillness of aftermath; we are in the charged pause where meaning is made. Caravaggio loved such hinges. He knew that the mind works most intensely when the world is about to tip and has not yet done so.

Contemporary Resonance

For modern audiences, “Saint Sebastian” often reads as a study in vulnerability that refuses victimhood. It speaks to anyone who has endured harm and chosen dignity. The bound hand, the small arrow, the stubborn lift of the head—these are recognizable gestures beyond their religious frame. They honor the human act of not looking away from one’s own suffering. In diverse communities Sebastian has become an emblem of resilience. Caravaggio’s version, stripped of pageantry, makes that emblem feel earned.

Why This Image Endures

The painting endures because it is unsentimental and merciful at once. It records a body and a moment with uncompromising accuracy, and it turns that accuracy into compassion. It shows how light can make a wounded person visible without exploiting them. It teaches an ethics of looking that remains essential: to pay attention, to refuse ornament where it would cheapen truth, and to allow beauty and pain to speak together without forcing a premature harmony.

Conclusion

Caravaggio’s “Saint Sebastian” condenses martyrdom to its human core. In a shallow chamber of darkness, a young man breathes after the first arrow. Light writes his body into being, and the knot of a white cloth holds the composition together like a promise. No crowd, no architectural stage, no cascade of arrows intrudes. The drama is the meeting of courage and harm in flesh, the second when the soul chooses its posture. With the fewest means—one arrow, one body, one beam—Caravaggio creates an image that feels both ancient and contemporary, sacred and painfully real. It is a lesson in how to look and, by looking, how to love the truth.