Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Saint Luke as a Painter before Christ on the Cross

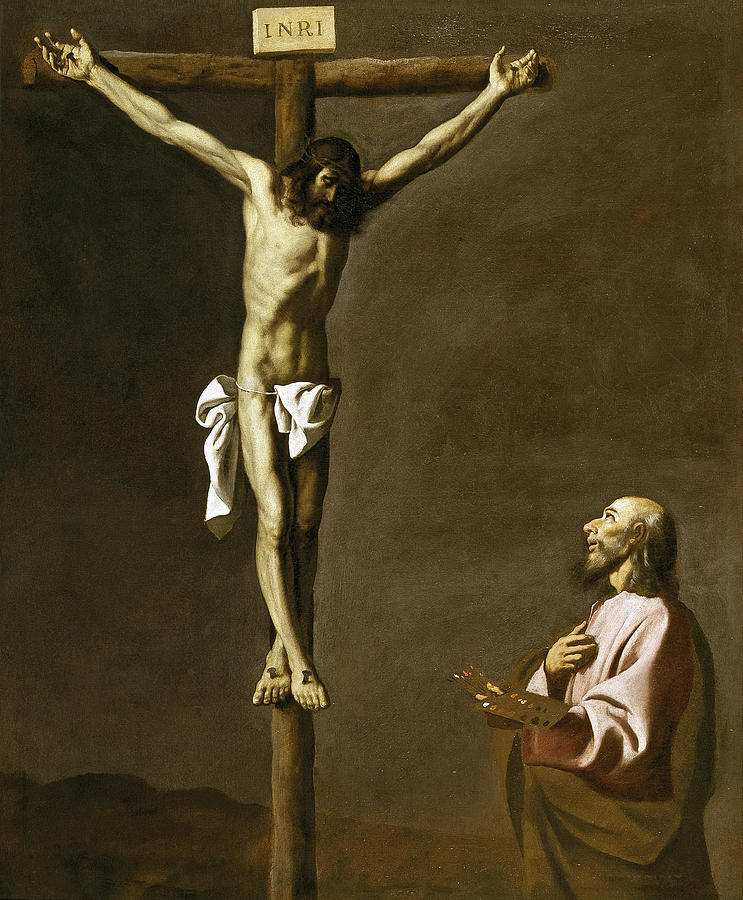

“Saint Luke as a Painter before Christ on the Cross” by Francisco de Zurbaran is one of the most striking visual meditations on the relationship between art and faith in Spanish Baroque painting. In this powerful image, the crucified Christ dominates the left side of the canvas, his body stretched along the vertical of the cross, while the evangelist Luke kneels humbly at the lower right, palette and brushes in hand, contemplating his divine model. There is no bustling crowd, no dramatic landscape. The scene unfolds in a vast, empty space where the focus falls entirely on the sacred figure and the devout painter who looks up in reverent awe.

Zurbaran transforms what might have been a simple representation of the patron saint of painters into a profound reflection on vocation, sacrifice and the purpose of sacred images. The work feels at once intensely personal and deeply liturgical, inviting viewers to recognise themselves in Luke’s posture and to understand art as an act of worship offered before the crucified Christ.

Historical and Devotional Context

The subject of Saint Luke painting the Virgin or the crucified Christ was popular in Catholic Europe during the seventeenth century. According to medieval tradition, Luke was not only a physician and evangelist but also an artist who painted the first image of the Virgin Mary. This legend elevated him as the patron of painters and, by extension, of artistic guilds and academies. For Zurbaran, a painter immersed in the intense spiritual climate of Counter Reformation Spain, Luke offered a perfect model of the ideal Christian artist, combining technical skill with deep interior faith.

Seville, where Zurbaran spent much of his career, was a major religious and artistic center. Monasteries and confraternities commissioned images that could inspire devotion and strengthen orthodox belief. In this context, a painting portraying Saint Luke at work before Christ on the cross would have served both as a didactic statement about the proper role of sacred art and as a spiritual mirror for the artists who viewed it. The message is clear. True painting does not exist for spectacle or vanity; it begins in contemplation of the mystery of redemption.

Although the exact date of this work is unknown, stylistic elements suggest that it belongs to Zurbaran’s mature period, when his characteristic combination of monumental simplicity, strong chiaroscuro and quiet emotional intensity reached full development. The painting sits comfortably beside his images of monks and saints, which often present solitary figures immersed in prayerful reflection. Here, however, the contemplative is an artist who encounters Christ not only as saviour but also as model.

Composition and Spatial Structure

The composition is built on a strong diagonal dialogue between the crucified Christ and Saint Luke. Christ’s body stretches along the tall cross that occupies the left half of the canvas. His arms extend outward in a broad V shape, creating a powerful horizontal that anchors the top of the painting. Luke kneels at the lower right, his head tilted upward, his gaze climbing the vertical shaft of the cross toward Christ’s downcast face.

This arrangement generates a dynamic tension between height and depth. Christ appears elevated and distant yet physically present, his body firmly modelled by light. Luke is closer to the viewer, painted at a slightly larger scale relative to his position, which makes him feel accessible. The contrast in scale and height emphasises the difference between the divine model and the human observer, while the invisible line of sight between them forges a spiritual connection.

The background is almost entirely empty, a broad expanse of muted brown that gradually darkens near the top. A low horizon line with vague hills or mounds barely interrupts the emptiness. This austerity heightens the drama of the figures. There are no architectural frames, crowds or atmospheric details. The cross stakes claim to the space like a solitary tree, and Luke occupies a modest corner of earth beneath it. The viewer’s eyes move naturally from Luke’s upturned face to the nailed feet of Christ, then along his body to the inscription “INRI” at the top, tracing the central mystery of the scene.

The Figure of Christ on the Cross

Zurbaran’s portrayal of Christ emphasises both physical suffering and serene acceptance. The body is slender yet muscular, modelled with great care. Light falls from the upper left, bathing the torso, arms and legs in a cool, even glow while leaving the face partially shadowed by the drooping hair. This lighting reveals the anatomical structure of chest, ribs and abdomen, but Zurbaran avoids the excessively graphic details found in some other Baroque crucifixions. There is blood at the hands and feet, but it is understated, allowing the viewer to focus on the expressive tension of the pose rather than on gruesome wounds.

Christ’s head leans to his right. The eyes are closed or nearly closed, and the mouth slightly parted. The expression is not one of active agony but of exhausted surrender, as if the moment captured is just before or just after death. The minimal loincloth, rendered in crisp white, stands out against both the flesh tones and the dark background. It serves as a visual hinge between spiritual purity and human vulnerability.

Above the head of Christ, the inscription “INRI” appears on a small board attached to the crossbeam. It reminds viewers of the official charge written by Pontius Pilate, identifying Jesus as “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” Zurbaran paints this sign plainly, with no ornament, emphasising its role as a factual statement of worldly condemnation that, in Christian belief, becomes a proclamation of true kingship.

The vertical pole of the cross penetrates the ground off center, slightly to the left of the midline. Its weight is palpable. The lowest portion of the wood appears roughly cut, as though thrust directly into the rocky soil. That physical solidity reinforces the reality of the event and anchors the spiritual drama in tangible matter.

Saint Luke as Devout Painter

In contrast to the naked, suspended figure of Christ, Saint Luke appears fully clothed, grounded and human. Zurbaran dresses him in a soft pink tunic and a muted beige mantle that catch the light in gentle folds. The colors are warm and earthy, harmonising with the background yet distinct from the cooler tones of Christ’s flesh. Luke’s bare head with receding hairline and short beard suggests an older man, perhaps in late middle age, someone whose life has been shaped by years of prayer and practice.

He kneels with his body turned three quarters toward us, but his face and eyes are directed upward. His left hand rests on his chest, fingers spread in a gesture that combines amazement, gratitude and personal offering. In his right hand he holds an artist’s palette along with a bundle of brushes. The palette is angled so that its colored patches are barely visible, indicating the potential for painting rather than its completion.

This detail is significant. Luke is not shown actively applying paint to a canvas. Instead, he is paused between contemplation and action. The tools of his craft are ready, but his attention is fully absorbed in the crucified Christ. Zurbaran suggests that true religious art begins not in the artist’s imagination alone but in a devout gaze fixed on the mystery it seeks to depict. Luke’s posture makes his entire body a gesture of prayer. He embodies the artist who works under the inspiration of faith, acknowledging his dependence on the model who is also his redeemer.

Light, Color and the Play of Chiaroscuro

Zurbaran’s mastery of light is central to the emotional impact of this painting. A single directional light source from the left illuminates Christ’s body and, to a lesser extent, the figure of Luke. The cross casts a subtle shadow behind Christ, blending into the dark background. The result is a dramatic yet controlled chiaroscuro that gives the figures sculptural presence against the void.

The palette of the painting is restrained. Flesh tones dominate the central area, flanked by the warm brown of the cross and the subdued hues of Luke’s clothing. The background remains a uniform, smoky brown that deepens toward the edges. This limited range of color enhances the solemn mood. There are no bright reds or intense blues to distract the eye. Instead, a quiet harmony reigns, aligning with the contemplative purpose of the scene.

The luminance of Christ’s body is the most striking chromatic feature. Although the tones are naturalistic, the way the light isolates his form against the dark field gives his figure a kind of spiritual radiance. Luke, by comparison, is partly in shadow. His face is lit enough for us to read his expression, but his body melts toward the darker right side of the canvas. This unequal distribution of light reinforces the hierarchy of holiness and also suggests that the artist’s illumination comes from the crucified One whose image he contemplates.

Symbolic Meanings in the Painting

Every element in the composition contributes to a rich symbolic network. The cross itself is the central symbol of Christian faith, representing not only suffering and death but also redemption and victory over sin. Its stark, unadorned wooden surface recalls the simplicity of older Spanish crucifixes and aligns with the austere spirituality of monastic orders that often commissioned Zurbaran’s works.

The inscription at the top functions on several levels. It identifies the historical event and emphasises the public nature of Christ’s execution. At the same time, for Christian viewers, it affirms Jesus as true king, hinting that humiliation on the cross becomes exaltation. Placing this sign within the same visual field as Luke’s palette invites reflection on the relationship between written word and painted image. Luke as evangelist recorded the story in words; as painter, he now seeks to render it in color and form.

The palette and brushes are more than professional tools. They symbolise the vocation of artists and, more broadly, the creative capacities of human beings. In Luke’s hands, they become instruments of praise, dedicated to the service of the crucified Christ. The fact that the palette is small and partly in shadow suggests humility and restraint. Artistic talent, in Zurbaran’s conception, is not a reason for self glorification. It is a gift that must be directed toward contemplation and proclamation of divine truth.

Even the empty background carries symbolic weight. The absence of architectural structures or crowds clears away distractions, leaving only the essential relationship between saviour and disciple. The low hills on the horizon hint at Golgotha, but they remain deliberately indistinct. Viewers are not drawn into a detailed narrative reconstruction. Instead, they are asked to remain with Luke in the timeless present of adoration.

Psychological and Spiritual Atmosphere

Despite the subject of crucifixion, the painting is remarkably calm. There is no stormy sky, no twisting figures writhing in grief. The emotion resides in inner attitudes rather than outward gestures. Christ’s body, though stretched and wounded, appears still and dignified. Luke’s expression is intense yet controlled, free from theatrical outcry. This quietness creates a contemplative atmosphere that suits meditative prayer.

The relationship between Christ and Luke generates a subtle psychological drama. Luke’s upward gaze is filled with reverence and, perhaps, professional awe at the beauty and pathos of the model before him. Christ, by contrast, does not look back. His head hangs, eyes closed, absorbed in his own sacrificial act. This lack of direct eye contact emphasises that the crucifixion is an event that transcends any individual observer, even a saint. Yet Luke’s position near the foot of the cross suggests that his contemplation allows him to participate spiritually in the mystery unfolding above.

For the viewer, the painting offers two possible identifications. One may stand at a distance, contemplating Christ as object of devotion. Or one may see oneself in Saint Luke, called to bring one’s gifts, however modest, before the crucified saviour. Zurbaran thus turns the picture into a mirror of vocational discernment. Anyone who works in a creative or expressive field can read the scene as a reminder that authentic creation begins in listening and looking, not in self assertion.

The Role of Art in Faith as Interpreted by Zurbaran

This painting can also be read as Zurbaran’s visual statement about his own profession. By presenting Luke in such a humble posture, he asserts that sacred art must be grounded in theological truth and heartfelt devotion. The goal is not mere imitation of nature but participation in the mysteries of faith. Christ on the cross is more than an anatomical challenge; he is the source and measure of all beauty and meaning.

Zurbaran’s own practice reflects this principle. Throughout his oeuvre he paints saints, monks and biblical figures with a sobriety and concentration that invite prayer. Here, by including an artist within the image, he acknowledges the mediating role painters play between the invisible and the visible. Luke is both viewer and maker. He receives the vision and then translates it into a form that others can encounter.

The painting therefore speaks not only to historical artists of Zurbaran’s time but also to anyone today who seeks to express spiritual themes through visual media. It suggests that the integrity of such expression depends on a living engagement with the subject, just as Luke’s painting depends on his direct encounter with the crucified Christ.

Place within Zurbaran’s Work and Baroque Art

“Saint Luke as a Painter before Christ on the Cross” fits naturally within the broader pattern of Zurbaran’s art. Like his celebrated depictions of Saint Francis, Saint Serapion and other religious figures, it reflects a preference for isolated individuals set against dark backgrounds, lit by a strong, focused light. This formula allows for intense psychological presence and emphasises personal relationship with God.

At the same time, the painting stands out because it shows a saint who is not only a model of piety but also a patron for the artist himself. It is a rare work in which the profession of painting is explicitly honoured and placed in direct relation to Christ’s sacrifice. In the wider context of Baroque art, the image participates in a tradition of self reflective painting that includes scenes of studios, artists at work and allegories of painting. Yet Zurbaran’s version remains distinctly devotional, far removed from the witty or secular self portraits found in other regions of Europe.

By focusing on Luke rather than on himself, Zurbaran avoids overt self promotion. Instead he links his own labour with that of a saintly precedent, suggesting that any artistic achievement worth having must be rooted in humility and faith.

Conclusion A Visual Meditation on Art and Sacrifice

“Saint Luke as a Painter before Christ on the Cross” is a masterpiece of quiet intensity. Through a simple yet powerful composition, Zurbaran brings together the crucified Christ and his evangelist painter in a space of contemplative encounter. The painting explores how art arises from the gaze of faith, how the tools of a craft can become instruments of devotion and how the mystery of the cross informs every genuine Christian vocation.

The stark cross, the luminous body of Christ, the humble figure of Luke with palette and brushes, and the vast, empty background all work together to strip away distractions and focus attention on the central drama of redemption. Viewers are invited to take their place beside Luke, to look upward at the crucified saviour and to consider how their own lives and talents might be offered in response.

Within Zurbaran’s oeuvre and within the broader history of Baroque painting, this work remains a profound statement about the sacred calling of the artist. It continues to speak to anyone who seeks to unite creative work with spiritual devotion, reminding us that the deepest source of inspiration lies not in the artist’s ego but in the silent, powerful presence of Christ on the cross.