Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

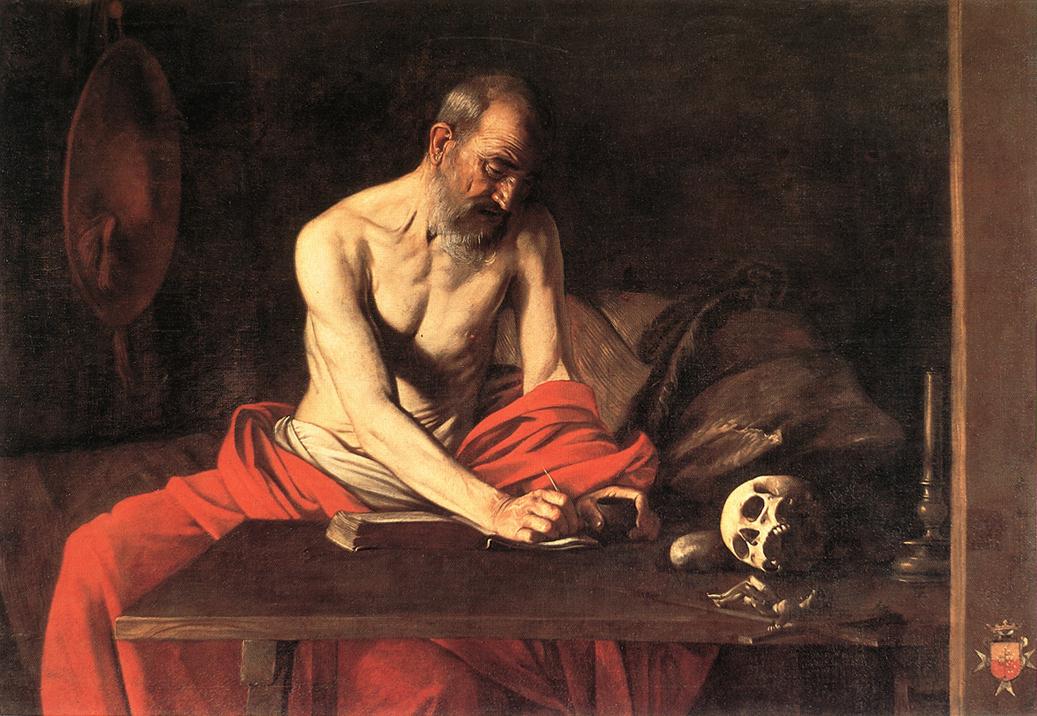

Caravaggio’s “Saint Jerome Writing” from 1607 is a meditation on intellect, mortality, and grace staged with the fewest possible elements: an aged scholar, a book, a skull, a candle, and a bench that doubles as desk and altar. The saint leans forward, quill poised, while a river of red fabric gathers and pools around his waist and across the tabletop. Darkness presses from every side yet yields where the painter’s light insists, as if revelation happened one plane at a time. It is a picture about the cost of thinking and the tenderness of attention, rendered with the tangible weight that marks Caravaggio’s Neapolitan period.

The Historical Moment And Caravaggio’s Neapolitan Turn

By 1607 Caravaggio was working in Naples after his escape from Rome. Exile tightened his art. He swapped architectural stage sets and anecdotal extras for chambers of shadow where figures emerge like facts. The city’s fervent devotional culture, with its appetite for images that could be prayed to rather than merely admired, met the painter’s evolving austerity head-on. “Saint Jerome Writing” belongs to that dialogue: it is a devotional image that trusts the reality of a single body and a few objects to carry both story and doctrine. Instead of a crowded study or desert cave, the saint inhabits an indeterminate room—more cell than studio—whose darkness behaves like architecture.

Saint Jerome As Scholar And Penitent

Caravaggio offers Jerome not as an ecstatic visionary but as a worker. The saint’s shoulders and back rise out of the red mantle with the strain of long labor; the left shoulder glows, the right falls into shadow, and the spine draws a pale furrow that records the hours. Jerome’s head tilts, eyes half-lidded, as if tracking a sentence through to its end. He is the translator of Scripture and the model of learned penance; Caravaggio fuses those identities in posture alone. The nude torso acknowledges asceticism, while the poised quill insists on intellect. Nothing about the face is idealized. Age is an instrument here, not an inconvenience, and wisdom appears as a way of paying attention to both book and skull.

Composition As A Tabletop Drama

The composition is a long rectangle punctuated by right angles. Jerome’s body creates a diagonal that travels from the exposed shoulder to the writing hand; the tabletop meets it like a threshold. Objects lie at the far edge, half within the lumen of the saint’s thought: skull at right, a candle beside it, bones and stone nearby, a small book used as a wedge to brace the parchment. The red mantle runs like a river from left to right, binding body, desk, and symbols into a single field. Behind Jerome, a cushion and bedroll hint at a place of rest that has been abandoned for work; even this softness reads as penance when set against the wooden plank and rough skull.

Chiaroscuro As A Form Of Thinking

Light falls from upper left and models the saint’s chest with sculptural care: clavicle, rib cage, and deltoid emerge one from the other like ideas generating implications. The light declines toward the writing hand, where fingertips and quill catch a decisive glint. The background remains a dense brown-black—not emptiness but a medium as thick as oil itself—so that each illuminated plane feels earned. In this painting, light behaves like thought: selective, clarifying, judgmental. It refuses ornament and chooses what matters.

The Still Life Of Bones, Book, And Candle

Caravaggio’s still-life cluster is a philosophical sentence. The skull is not a prop but an interlocutor, leaning toward Jerome like a companion in dialogue. The candle—snuffed or yet unlit—is time arrested, a column of wax that will vanish once fire begins its work. Bones on the tabletop double the skull’s reminder, and a stone lies nearby, recalling the ascetic’s practice of striking his chest or the desert ground in contrition. The small book used as a wedge is a beautiful practicality: learning serves devotion; theory props up the page so truth can be written clearly. Every object operates at both literal and symbolic levels and is painted with the exacting tenderness usually reserved for faces.

Anatomy And The Ethics Of Realism

Caravaggio’s Jerome is no marble hero. Muscles are softened by age; skin shows the slight looseness that comes with fasting and years. Yet the body is undeniably powerful. The painter relishes the way light grazes the serrations of the serratus anterior, the thin film of skin over the ribs, the ropey forearms that have lifted books and held quills for decades. The realism is ethical: by refusing to idealize the saint, Caravaggio honors a holiness achieved in a mortal body. The viewer recognizes a familiar anatomy and is invited to imagine a familiar conversion.

Color As Emotional Weather

The palette is austere—earths and flesh tones tempered by the enormous mantle of red. That red is not festive; it is ardent, sacrificial, closer to the color of coals than to celebration. It warms the composition without dissolving its gravity. The rest is a measured scale of umbers and ochres that flips between warm light and cool shadow. Subtle green-gray notes in the skull and bone check the heat of the mantle and keep the image balanced on the edge between contemplation and warning.

The Table As Altar And Desk

Caravaggio’s plank is both desk and altar. It hosts the book to be written and the relics of mortality side by side. Its near edge, sharply lit, is like a step toward the viewer’s space, inviting entry into the saint’s labor. The far edge, where the skull sits, meets darkness like a shoreline meets night sea. The table’s roughness keeps the picture grounded; its function is utilitarian, yet because it supports the writing of scripture, it becomes liturgical. The dual identity supplies the painting’s quiet drama: scholarship as sacrifice, pen as instrument of worship.

Space Reduced To Conscience

There is little architecture beyond the bedroll, rounded shield or drum hanging at left, and the horizontal of the table. The room is defined by darkness that acts like a wall, absorbing anything that would distract. This spatial parsimony is also spiritual. The saint’s world is narrowed to essentials: text, memory of death, light enough to see by. The viewer encounters the same economy and must ask which objects on his own table belong to necessity and which to noise.

Gesture, Gaze, And The Time Of The Painting

Caravaggio chooses a moment that feels both instantaneous and unending. Jerome’s quill is mid-stroke; the other hand steadies the page; the head inclines in the manner of someone silently sounding out a line. The painting therefore reads as a continuous present, the kind of time one enters during study or prayer. Even the shadows obey that slowed tempo; they do not rush, they accrue. The viewer is not invited to anticipate an event but to inhabit a state—concentrated, penitent, generous toward detail.

Brushwork, Layers, And The Persuasion Of Paint

The surface shows the painter’s late economy. A warm ground provides middle value; the deepest areas are thin, transparent passages that let the ground glow through like breath under skin. Flesh is built with semi-opaque strokes laid confidently across larger pools of tone; sharp highlights—on shoulder, knuckles, skull—are placed sparingly, like the final words in a carefully revised sentence. Edges alternate between crisp and lost. The contour of the saint’s shoulder catches a hard light; the boundary where torso dissolves into shadow is softened, encouraging the eye to move without snagging. Caravaggio’s paint thinks for the viewer, guiding attention and meaning.

Comparison With Caravaggio’s Other Saints Jerome

Caravaggio revisited Jerome more than once. Earlier versions emphasize an angel’s dictation or the table’s frontal grandeur. This 1607 canvas pushes us closer to the man and pares away intermediaries. There is no winged messenger; illumination arrives as light alone. The emphasis on the torso’s twist and the precarious staging of objects on the table reflect the Neapolitan appetite for immediacy. If the Roman pictures are symphonic, this one is a quartet: fewer instruments, more space for each line to be heard.

Theological Reading Encoded In Material Facts

The theology is plain and rigorous. The skull is memento mori, but placed beside the book it also blesses learning with humility: knowledge without the memory of death becomes vanity. The candle stands for time and spirit; its unlit state allows the saint’s interior flame—the one lighting his chest and hand—to become the true illumination. The red mantle evokes both cardinalate dignity and martyr’s charity, making the scholar’s labor a form of witness. The quill’s arc across the page is not just writing; it is translation, the act that moved scripture into the common tongue of the Latin West, and therefore a form of incarnation.

The Humanity Of Sanctity

What distinguishes this painting is the humanity with which it handles sanctity. Jerome is not seated on a throne of books nor set in a landscape of signs. He is tired, intent, and gentle with his tools. Even the skull is treated gently; it is a neighbor, not a prop. Caravaggio’s compassion for work transfigures the entire scene. The saint’s holiness appears not in the fireworks of vision but in the ordinary courage of staying with a demanding task.

The Viewer’s Place In The Room

The desk’s near edge and the saint’s forward lean draw viewers into the space of study. We stand where the quill will soon travel. The composition therefore implicates us. Do we become colleagues, lending our attention to the same text, or do we remain visitors, impressed by the spectacle of concentration? Caravaggio quietly asks for collaboration. He stages the picture so that the viewer’s silence becomes part of the saint’s labor, as if the painting could be finished only in the minds that contemplate it.

Mortality, Memory, And The Craft Of Translation

Jerome’s task—translating sacred words—depends on memory as much as on grammar. The skull beside the page is memory’s anchor. It says that language must answer the body’s destiny and that words worth writing must be hospitable to endings. That is why the torso, so carefully modelled, matters: flesh is the text that all other texts interpret. When Caravaggio paints a rib cage as precisely as he paints a book’s edge, he aligns scripture with incarnation. The saint grasps this truth with both hands, one on page, one steadying the parchment’s edge. The scene is not only about what he writes; it is about what writing is for.

Material Culture And Sacred Poverty

The objects on the table are few and modest. The book is unadorned, the candle simple, the skull unpolished, the stone unremarkable. Even the bedroll looks coarse. This material humility echoes the Counter-Reformation’s demand that images teach without distracting ornament. Yet Caravaggio avoids didactic stiffness. He paints each thing as if it had a biography: the book’s corners worn by fingers, the candle nicked by earlier flames, the skull’s surfaces smoothed by devotion. Poverty becomes specificity; holiness happens in the details of use.

Influence And Afterlife

“Saint Jerome Writing” shaped how later painters imagined the scholar-saint: Rembrandt’s monks at tables, Ribera’s solitary philosophers, and countless Neapolitan tenebrist studies trace back to this image’s grammar of light and labor. Beyond art history, the picture persists in cultural memory as a template for serious work done under pressure—night, deadline, conscience. In a world saturated with noise, the canvas demonstrates the elegance of reduction: a body, a task, a truth told in light.

Conclusion

Caravaggio’s 1607 vision of Jerome is both intimate and monumental. It turns a small room into a theater where time, language, and mortality negotiate a covenant. Light judges without cruelty, shadows protect concentration, and color warms the chill of bones. The saint’s back carries the weight of centuries and yet remains simply a back, mortal and tender. Few paintings make thinking look so physical or devotion so exact. To remain with it is to feel one’s own posture change, to sense the quill in your fingers, and to hear in the quiet the sentence you have been avoiding begin, finally, to form.