Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

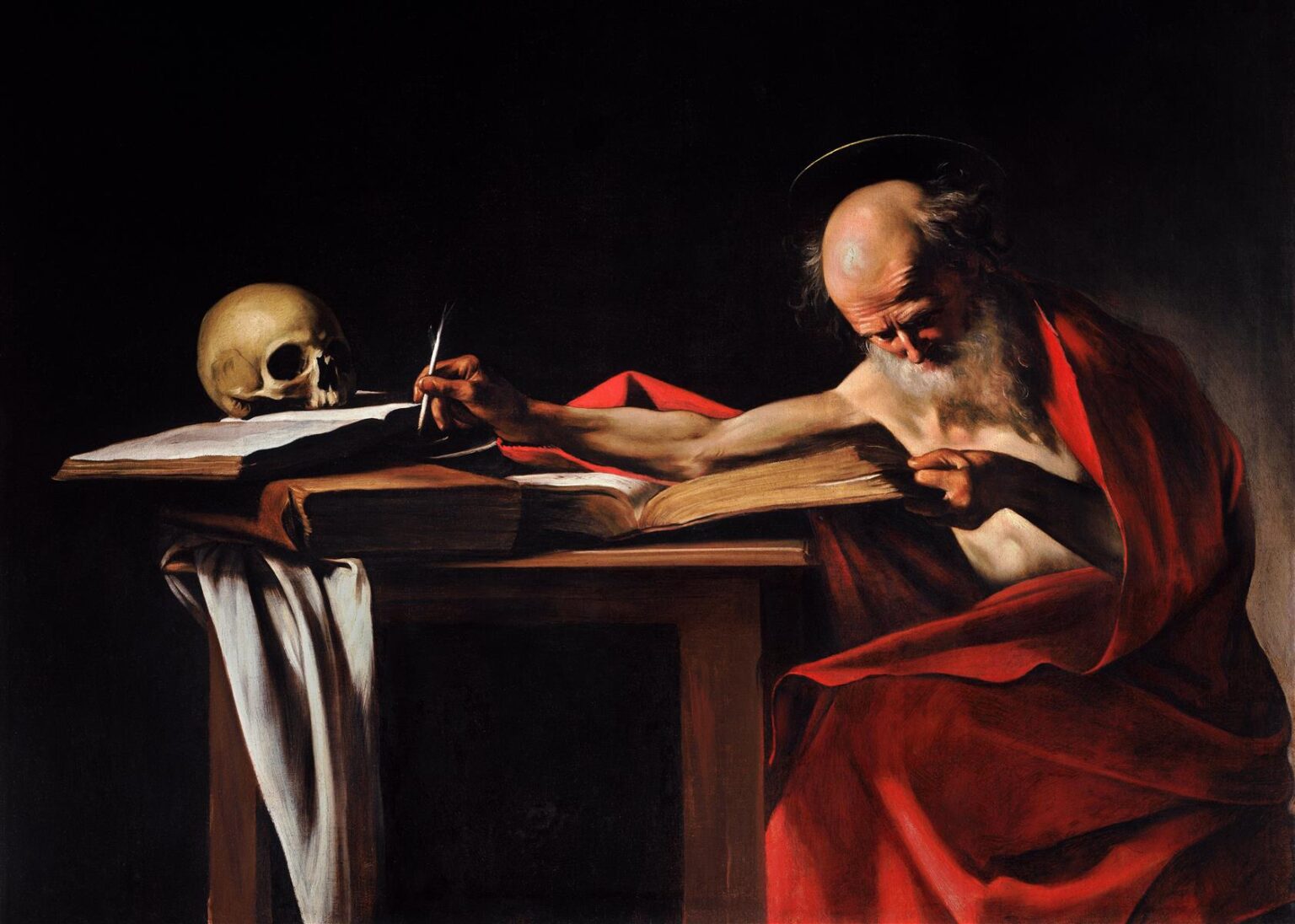

Caravaggio’s “Saint Jerome Writing” (1605) is a portrait of intellectual fire sharpened by mortality. An old man in a red mantle bends over a massive book, quill extended toward a page that lies beside a skull. A long beam of light cuts across the scene so decisively that objects feel carved from darkness rather than placed in it. There is no vista, no library, no furniture beyond a rough table, a draped cloth, two volumes, a feather, and a bone-white cranium. With these essentials, Caravaggio turns the scholar-saint into a living instrument of translation, his body stretched between the book he consults and the page he writes, his thought bridged by an arm that seems almost too long for the task. The painting condenses the labor of a lifetime—the Latin Bible, the Vulgate—into one concentrated gesture.

Historical Context and Subject

Saint Jerome (c. 347–420) is the church’s great translator, remembered for rendering Scripture into Latin and for his ascetic life in the desert. By 1605, Jerome had become a favored subject for Baroque artists because he allowed painters to stage an encounter between learning and penitence, intellect and death. Caravaggio’s Rome prized devotional images that were legible to common worshippers and psychologically convincing to the learned. The artist answers with an image stripped to the bone. No lion, no desert cave, no heap of erudite props: just the scholar, his books, and the friendly skull that keeps time. In Counter-Reformation terms, it is an ideal: clarity of doctrine (Scripture), clarity of moral purpose (penitence), clarity of destiny (mortality), all modeled with unflinching naturalism.

The Chosen Moment

Caravaggio arrests Jerome at a hinge of action, not beginning or finishing but transferring. The saint’s left hand grips the consultation volume; the right arm reaches, quill poised to set a word onto the waiting page. His head inclines in severe concentration, bald crown haloed by a thin ring of light. The skull sits near the page like a quiet editor. Nothing is extraneous to the act. Even the mantle, red as embers, has slid from the shoulder to free the arm for work. The moment vibrates with purpose because it is so ordinary: a person writing, caught between what was read and what must be said.

Composition as a Bridge of Thought

The picture’s structure is an exercise in long diagonals and right-angled anchors. Jerome’s arm forms the dominant diagonal, a muscular bridge running from the consulted book to the blank page. The table’s front edge gives a stabilizing horizontal; the vertical of its leg locks the mass like a lintel. The skull, left of center, occupies the space where a companion might sit; its roundness softens the geometry and, by mirroring the bald head of the saint farther right, creates a visual rhyme: skull to skull, bone to living mind. Three great triangles run through the design—the mantle’s fold, the open book’s wedge, and the wedge of light that begins at the saint’s head and lands on the page. These shapes corral attention onto the channel of work, sharpening the sense that the entire studio bends toward the word Jerome will write next.

Chiaroscuro and the Ethics of Light

Light is the picture’s principal moral actor. It arrives raking from high left, striking first the skull and the white of the page, then traveling along the sinews of the extended arm, then pooling across the saint’s shoulder and head before dissolving into the red cloak. This beam functions like a rule of life: remember death, enact the sentence of work, submit the mind to illumination. Darkness provides a capacious backdrop, refusing any distraction. Tenebrism here is not theatrical violence; it is discipline. Things are permitted to exist only insofar as they serve Scripture and thought. Even the linen draped over the table breathes light with austerity, the folds described by a handful of decisive strokes.

The Body as Instrument

Caravaggio’s anatomy carries meaning. Jerome’s torso is lean, the skin loose at the ribs, the muscles in the forearm corded by use rather than by show. The long reach reads as effort distilled; the tendons pull like strings on a bow, firing meaning from book to page. The left hand’s grip on the folio is a laborer’s hold, thumb locking the quires, fingers bracing the fore edge so the text will not slip. The eyes, half in shadow, do the work of a monk at matins—close reading more felt than seen. This is not a heroic athlete painted as a scholar; it is a scholar whose heroism is stamina and accuracy.

The Red Mantle and the Color of Zeal

Jerome’s cloak flares a deep, iron-rich red, a hue associated with cardinals and with the burning of charity. Caravaggio makes it heavy and practical: it warms the body, provides a field for light to articulate form, and dignifies the subject without gilding him. The cloak also offers the painting its only saturated chroma, allowing the flesh tones to register as humanly warm against a sea of browns and blacks. Where the mantle catches the beam, it glows like banked coals. Where it falls into shadow, it reads as a weight the saint gladly bears—habit, duty, and protection.

Books, Quill, and the Page That Waits

The two volumes are characterized with lover’s attention: the swollen spines of parchment, the deckled edges, the slow give of vellum that tells you these are not neat printed tomes but manuscripts heavy with history. Caravaggio paints the book under Jerome’s hand as a living thing, the pages splayed like gills, the paper rough enough to bite into a quill’s nib. The feather itself—a narrow, angled line—describes a vector from thought to inscription. The page near the skull is not blank; faint lines are sketched in, but its central field glows emptier than the rest, an open future. Everything conspires to ask the delicious question: what word will come next?

The Skull and the Literature of Vanitas

Memento mori had become a visual habit in Catholic Europe, but Caravaggio’s skull is unusually companionable. It is not tucked into a corner or rendered as a scarecrow prop. It rests beside the open page, on the same plane of use as the book. The proximity transfigures it from threat to tutor. Its sockets aim toward the writing hand; its jawline echoes the slope of the quill. In this company the skull reads not as morbidity but as clarity. For Jerome, death is not a negation of thought; it is the memory that keeps thought honest, preventing the scholar from confusing ink with truth or memory with hope.

The Halo and Sanctity as Availability to Light

The halo is a thin, almost reluctant ring. Caravaggio refuses the golden trumpet of radiance; he paints a whisper. Holiness is not spectacle here but availability—skin exposed to illumination, attention given to the task that God has placed on the table. The ring hovers at the head like a margin note: this is sanctity as studiousness. The effect dignifies labor itself. Sanctity arrives not with ecstasy but with a steady hand and a mind that knows what matters.

Space, Proximity, and the Viewer’s Seat

The shallow space and low table lip place the viewer at the saint’s elbow. We stand where a novice might stand, close enough to see the small tremor on the quill’s point or the notch cut into the book’s fore edge. The staging removes museum distance; the image reads like an invitation to apprentice. Caravaggio does not stage Jerome on a throne of books or in a grand library. He is a worker at a workbench. By trimming space to only what the task requires, the painter suggests that wisdom does not need a theater—only light, time, and a table.

Technique and the Persuasion of Paint

Caravaggio builds the scene with large shadow masses that swallow everything not essential. Over this bedrock he floats midtones until volumes breathe and then needles the eye with small, controlled highlights: a bead of light on the skull’s brow ridge, a chalky edge on a page, a glint on the tendon at the saint’s wrist. The brush moves long and economical across the cloak, then switches to tight, almost calligraphic flicks along the book edges and the quill. Flesh is layered thinly, translucence letting a warm ground show through cool greys so that the body looks lived-in rather than polished. The result is a surface that declares facts without fuss, a perfect mirror of the subject’s ethic.

Comparisons with Other Jeromes

Painters before and after Caravaggio often amplified the narrative: lions at the saint’s feet, a stone for penitential beating, landscapes, altars, angels dictating. Caravaggio keeps only what serves translation. Compared with his earlier “Penitent Magdalene,” where sanctity is repose, here sanctity is reach. Compared with his “Inspiration of Saint Matthew,” where an angel swoops to guide a Gospel writer’s hand, Jerome is on his own: the only angel is light. This independence makes the painting quietly radical. It insists that God’s grace is fully compatible with the rigor of scholarship; revelation does not negate discipline, it uses it.

The Psychology of Concentration

The head tilt, the furrow between brows, the slightly pursed mouth—these small elements add up to a portrait of attention. Caravaggio paints not just a saint who writes, but a mind in flow. The long arm that many viewers note as exaggerated is psychologically right; it feels like what concentration does to the body: stretches it toward the object, lengthens reach, narrows world. Even the cloth draped over the table contributes to this mentality; its weight quiets the edge, mutes the scrape of wood, and helps us hear the whisper of the quill.

Color and Emotional Weather

The palette’s austerity keeps the mood courageous and calm. Reds, bone-whites, honeyed flesh, deep browns, and the black of the abyss set an atmosphere of serious joy. There is no cold blue to chill the scene, no gilded ornament to flatter it. The red mantle warms and warns; the whites of page and cloth offer clearings in the dark; the browns steady the eye like earth. The emotional climate is monastic afternoon, the hour when light is high yet tender and work feels both finite and infinite.

Gesture as Theology

Caravaggio lets gesture preach doctrine. The left hand holds tradition; the right hand writes translation. The arm between them is the church at work across time. The tilted head confesses humility before the text. The mantle acknowledges office and responsibility, but it slides back to free the arm, a visual promise that status will not obstruct service. The skull keeps the sermon honest: all this labor is for mortals who die, and therefore every good word must be practical, consoling, exact.

The Page as Future

One of the painting’s most moving effects is the glowing field of the page Jerome is about to mark. Nothing in the canvas is brighter. The virgin paper becomes a theological symbol: the future of faith depends on words carefully chosen by the living, aware of the dead, obedient to light. The saint’s shadow almost touches the margin, as if to remind us that even the holiest scribe writes under limits—time, body, breath—but that these limits, accepted, become the place where meaning takes ink.

How to Look

Begin at the white cloth and the skull that share the table’s edge. Let the light guide you along the quill to the blank page and ask yourself what word you would write. Follow the long diagonal of the arm back to the consulted book and feel its weight. Climb to the saint’s head and note the fine ring of the halo, the concentration of the mouth. Drift across the mantle’s field and watch how red falls into darkness. Then make the circuit again more slowly, feeling how gesture, light, and objects form a single sentence: remember, study, write.

Devotional Meaning for a Modern Viewer

The canvas honors any vocation that translates difficulty into nourishment. You do not have to be a monk to recognize the truth of tools, tables, and deadlines. Caravaggio offers the dignity of attention in an age that starves for it. He shows that the pursuit of understanding can be a form of prayer, that mortality clarifies rather than depresses, and that the most persuasive miracles are not spectacles but sentences shaped under a good light.

Conclusion

“Saint Jerome Writing” distills intellect, penitence, and mortality into the simplest stage: a table in a dark room. With a beam of light, a red cloak, two books, a feather, and a skull, Caravaggio composes a hymn to concentration. The saint is not a legend; he is a worker who knows what matters and gives himself to it. The painting’s authority arrives from restraint. There are no angels dictating, no lions roaring—only the long arm of a man who reads, remembers death, and writes so others may live by the Word.