Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

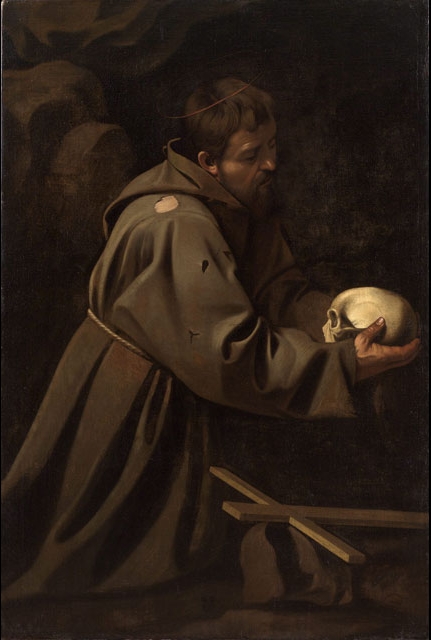

Caravaggio’s “Saint Francis in Prayer” (1610) is a late, distilled meditation on poverty, mortality, and grace. The saint kneels in a cave-like darkness, his patched habit pooling around him as he cradles a skull with both hands. A rough wooden cross rests on the ground in front of him. No landscape, choir of angels, or decorative architecture competes with the encounter. Caravaggio reduces the scene to three essentials—Francis, the skull, and the cross—and then lets light perform the theology. A sharp beam grazes the friar’s face and sleeves, polishes the skull to a fragile glow, and leaves everything else to silence. What emerges is not a legend spread across space but a prayer held within breath. It is a painting about looking at the end with honesty and discovering, inside that honesty, a new beginning.

Historical Context and the Artist’s Late Style

By 1610 Caravaggio had refined his language to an austere clarity. Years of flight, imprisonment, and petitions for pardon had stripped away ornamental devices. The late canvases favor shallow settings, small casts, and a tenebrism in which illumination chooses rather than describes. “Saint Francis in Prayer” belongs to this late phase and to a broader devotional culture that prized the example of Franciscan humility. In Seicento Italy, Capuchin and Observant houses encouraged images that ordinary believers could understand at once. Caravaggio’s realism—patched cloth, worn cord, the weight of a skull set in soft palms—answered that pastoral need while maintaining artistic authority. The result is an altarpiece for the private soul, a picture designed to function in a side chapel or oratory as a companion to silence.

Composition and the Architecture of Bodies

The composition is built from a stable triangle. At its apex, Francis’s head leans forward in profile, eyes lowered to the skull. The base is formed by the spread of his habit and the laid cross. Everything funnels toward the fragile oval caught between his hands. Caravaggio sets the figure slightly off-center so that the diagonal from the saint’s head to the cross keeps the painting alive with tension. The habit’s folds create a rhythm of large, shadowed planes that make the skull’s ivory smoothness startling. Space is shallow; the dark stone at left reads as the wall of a grotto. The absence of depth locks the viewer into the same small chamber as the saint, a tactic consistent with Caravaggio’s lifelong strategy of putting sacred moments at arm’s length.

Tenebrism and the Beam of Grace

Light in this painting is an event. It finds Francis’s brow, knuckles, and sleeves and then spills onto the skull, establishing a chain of attention that becomes prayer itself. The background remains nearly black. No torch or candle is shown, yet the beam feels natural—like a stray shaft that has slipped through a crack in the rock. In Caravaggio’s late works such light often functions as grace: unearned, directional, uninterested in decoration. It both reveals and judges. Here it honors the poor habit as surely as it clarifies the emblem of mortality. In so doing it declares the pair—poverty and death—worthy of contemplation rather than avoidance.

The Habit, Cord, and the Vows Made Visible

Francis wears the coarse brown of his order, cinched with a rope. Caravaggio paints the cloth with tactile heaviness: stitched seams, thin spots, a visible patch near the shoulder. The habit is not costuming; it is biography. It tells the viewer, without inscription, about the saint’s embrace of poverty. The rope cord is tied with knots that in Franciscan tradition recall obedience, poverty, and chastity. Set against the skull’s polished bone, the fabric’s weight implies a discipline planted firmly in the practical world. Caravaggio insists that sanctity lives in the ordinary materials of daily life—cloth to keep warm, rope to secure a promise, wood to mark a cross.

The Skull as Memento and Mirror

The skull is not a prop of horror; it is an instrument of clarity. Francis does not recoil from it or wield it theatrically. He holds it gently, as one might hold a fragile vessel or a relic. The bone’s pale sheen records the painter’s gift for surfaces, but the object’s meaning is interior: remember death. In the Counter-Reformation, such memento mori were common, yet Caravaggio’s treatment is unusually compassionate. He gives the skull a tender polish, as if reminding viewers that mortality is not the enemy but the context in which love and fidelity become urgent. The saint’s gaze suggests not dread but recognition. To look at the skull is to read one’s own life with honesty.

The Cross on the Ground and the Way of Descent

Two rough boards form a cross on the floor, low and unexalted, nearly blending into shadow. The sign is there to be knelt beside rather than admired. Caravaggio places it where the viewer’s eye arrives last, after following the light’s path from face to hands to skull. The progression is deliberate: knowledge of death leads to the cross, not as spectacle but as a way. In Franciscan spirituality the imitation of Christ means a downward path—toward the poor, toward humility, toward wounds accepted in love. By placing the cross at knee level, Caravaggio turns symbol into posture. To see it truly, one must bow.

Gesture as the Grammar of Prayer

Caravaggio composes with hands. The saint’s fingers cradle the skull with an economy of pressure that reads as reverence. His shoulders slope in a quiet arc, the curve of a man gathering himself inward. The mouth is closed; the eyes nearly so. Nothing in the face is theatrical. The prayer occurs in the body’s small decisions—weights shifted, elbows drawn in, head inclined. This restraint keeps the scene credible and transferable. Viewers can, in their own rooms, copy these gestures and thereby find entry into the saint’s practice. The painting is devotional technology as much as picture.

Psychology Without Spectacle

Much religious art of the period communicates sanctity through ecstasy—eyes upturned, lips parted, drapery flung back in rapture. Caravaggio chooses comprehension instead. Francis is absorbed, but not transported. He appears to be thinking with his whole body, allowing the facts in front of him—the skull, the rough cross, the darkness of the cave—to order his heart. This psychological realism is central to the painter’s project. It affirms that encounters with God may look like concentration rather than display, and that a life of prayer can be legible in the quiet of a room.

The Cave as Interior Wilderness

Although barely described, the rocky backdrop matters. Francis often withdrew to grottoes and hermitages; Caravaggio echoes that setting to locate the saint on the margins of society where conversation with God becomes possible. But the cave is also metaphor. A shallow, unornamented space stands in for the interior chamber of the soul where distractions have been removed. The blackness is not threat but invitation. Within it, the smallest glints of light—on a fingernail, a fold, a jawbone—take on luminous importance. The painting trains the eye to notice grace where there is little else to see.

Color, Palette, and the Poetics of Restraint

The palette is almost monochrome: brown habit, gray-brown stone, the warm beige of bone, a few pinkish notes in the hands and face. Caravaggio uses restraint as a virtue, allowing tonal subtleties to carry feeling. Against this earthbound harmony the skull’s pale oval reads as a bright word in a quiet sentence. The limited color forces attention toward structure and light; there is no gilded distraction, no cool landscape receding into distance. The effect is as modern as it is Baroque: clarity achieved through subtraction.

Technique and the Convincing Flesh of Truth

Caravaggio’s oil handling is precise without pedantry. The habit’s broad planes are laid in with confident, opaque strokes that catch just enough reflected light to describe volume. Hands and face are modeled with tighter values, giving skin a lifelike translucency as the beam moves across it. The skull is polished with small, firm highlights along brow and zygomatic arch, proof of the painter’s observation. Nothing is over-finished; a few strokes suffice to suggest a hem or a nicked edge on the wood. The surface supports the illusion without calling attention to labor—a signature of the artist’s late confidence.

Franciscan Theology Made Visible

The painting is an image of the Franciscan charism translated into objects and posture. Poverty appears in the patched garment and the absence of luxury; humility in the kneeling stance and the lowered gaze; meditation on the Passion in the cross; contemplation of mortality in the skull. Yet none of these are treated as programmatic symbols. Caravaggio makes them credible by the way they inhabit the same world of light and texture as the viewer’s own body. The saint’s sanctity is not a haloed abstraction (though a faint thread of light circles his head); it is a way of being with things—cloth, bone, wood—in truth.

Dialogue with Earlier Francis Images

From Giotto onward, painters had portrayed Francis receiving the stigmata, preaching to birds, or embracing a crucifix. Caravaggio advances a more intimate icon: the saint alone with a skull. Earlier Counter-Reformation artists sometimes dramatized memento mori with theatrical lighting and elaborate still-life arrangements. Caravaggio, by contrast, strips the motif to essentials and enlists tenebrism to soften rather than sensationalize. The innovation is subtle but influential. Later artists will borrow his close framing and quiet psychology to create Franciscan images designed for personal prayer rather than public processions.

Viewer’s Position and the Ethics of Nearness

Because the figure nearly reaches life-size and the space is shallow, the viewer stands within the saint’s orbit. This nearness is not invasive; it is invitational. The picture asks you to kneel, if only inwardly, to adopt the angle from which the skull and cross are seen. Caravaggio often composes to enlist the viewer as participant. Here that enlistment serves the painting’s purpose as a spiritual exercise. It is easier to imitate what you can see up close, easier to let the saint’s calm become your own when the image is built from gestures the body can remember.

Silence as a Subject

The dominant impression of the canvas is quiet. The brush has left no glitter, the composition no loud diagonals, the color no sudden shouts. Even the light behaves with courtesy, touching and passing on. This silence is not emptiness; it is charged attention. Caravaggio’s genius is to make silence visible, to turn looking at a skull into a credible form of prayer. In a devotional culture crowded with eloquent preaching and lavish ceremony, such a picture would have offered worshippers another route: the abstention from noise that allows the smallest truths to register.

The Saint’s Face and the Work of Memory

Look at Francis’s profile: the brow gently creased, the eyelids lowered but not shut, the mouth relaxed. It is the face of someone remembering. Perhaps he recalls his embrace of the leper, his renunciation before the bishop, or the nights when he begged God for a sign. Caravaggio refuses to specify because he wants the viewer’s own memory to enter the scene. The skull is a universal. All humans, saint or not, must learn to look at their end and choose how to live in light of it. The painting models a way of remembering that is neither bitter nor sentimental: honest, tender, and firm.

Function in Devotion and Everyday Practice

As an object of prayer, this image teaches technique. It asks you to hold mortality with both hands, to measure it not with dread but with respect, and then to lay it at the foot of the cross that is never far from the ground. It encourages poverty of attention—focusing on a few things deeply rather than on many things shallowly. In that sense it is also a remedy for the distracted mind. Like a spiritual director who says “start here,” the painting offers a small, repeatable exercise: breathe, look, accept, and ask.

Contemporary Resonance

Modern viewers often find “Saint Francis in Prayer” unexpectedly contemporary. Its minimalism, tactile realism, and contemplative mood feel at home in an age seeking quiet. The painting refuses triumphalism and respects grief; it acknowledges the body’s finitude without despair. In a culture anxious about endings, Caravaggio offers an image in which acceptance becomes a form of peace. The saint’s patched sleeve and the simple cross suggest that the resources for such peace are not exotic. They are the humble materials already within reach.

Conclusion

“Saint Francis in Prayer” is one of Caravaggio’s purest statements. With a handful of objects and a disciplined beam of light, he builds a room where a human being meets truth without drama. The saint’s rough robe, the skull’s clean oval, the low cross, and the surrounding dark together create a pedagogy of humility. In that humble space, grace appears not as spectacle but as clarity. The painting’s achievement is to show sanctity as a way of paying attention—of holding mortality honestly, bending near the cross, and letting light teach the hands how to rest. At the end of a turbulent life, Caravaggio leaves us an image of lasting calm.