Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context of 1928

In 1928, Europe teetered between the cultural exuberance of the Roaring Twenties and the political tremors that would lead to global upheaval. The Weimar Republic in Germany experienced a flowering of avant-garde art, theater, and literature even as economic crises and rising nationalist movements cast shadows over daily life. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, although physically withdrawn in the Swiss Alps since 1917, remained intellectually and emotionally invested in the artistic discourses of Berlin and Dresden. His travels between Davos and urban centers infused his work with dual sensibilities: the solitude and regeneration of mountain air alongside the restless innovation of metropolitan modernity. Rower, painted in this liminal year, encapsulates those tensions, marrying a subject drawn from contemporary leisure—with its modern athleticism and mechanized boats—to a painterly language charged with Expressionist urgency.

Kirchner’s Late Berlin Period and Artistic Transitions

By 1928, Kirchner’s early Die Brücke fervor had matured into a refined synthesis of bold gesture and compositional clarity. His pre-war canvases had pulsated with the frenetic energy of city street scenes, raw color contrasts, and jagged linework. In the post-war years, the alpine environment offered him respite and new pictorial registers—air, light, and natural forms. Yet his return visits to Berlin’s rowing clubs and riverside cafés rekindled his fascination with the modern body in motion. Rower reflects this hybrid phase: its subject is unmistakably urban and athletic, but its handling of pigment and form bears the quiet intensity of alpine studios. In this period, Kirchner navigated between two worlds—one shaped by communal vigor, the other by solitary exploration—embedding both in his layered visual commentary.

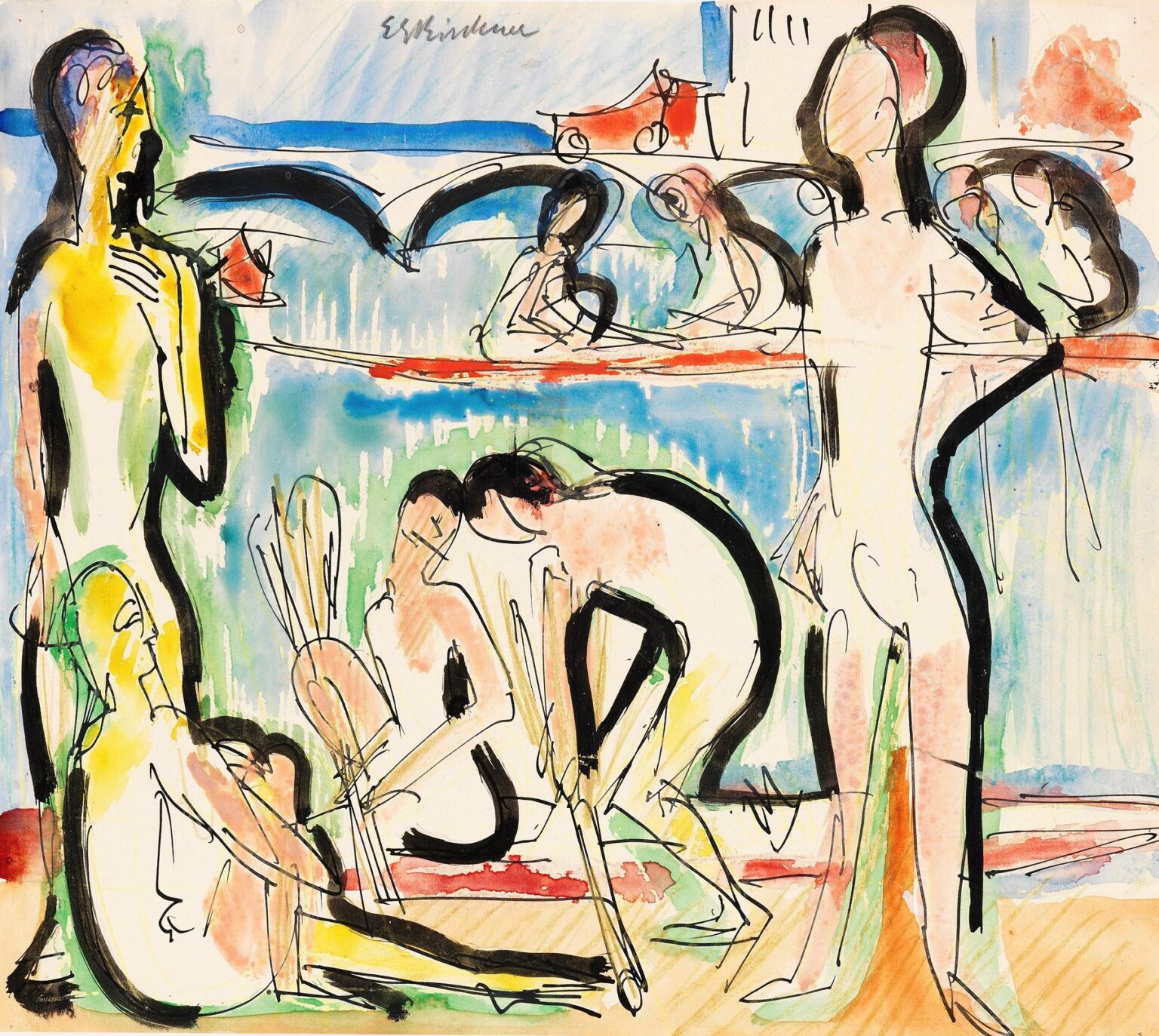

Subject Matter: The Rower and His Ensemble

At the heart of the painting stands a solitary rower, his oars poised for exertion. Flanked by fellow athletes—some seated in shells, others perched on the riverbank—the central figure commands our attention through scale and posture. Their bodies, elongated and stylized, emphasize musculature and the ritualized choreography of competitive rowing. A distant backdrop of tree-lined banks and swaths of water anchors the scene in recognizably riverside terrain, yet details blur into abstraction. Rather than a single portrait, Rower presents a tableau of interrelated action: the solitary discipline of the athlete intertwined with communal moments of rest and preparation. Through this ensemble cast, Kirchner explores the social dynamics of sport as a modern ritual of camaraderie, discipline, and individual challenge.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Kirchner arranges the composition to emphasize both movement and stasis. The rower’s angular torso and outstretched arms form a series of diagonal axes that cut across horizontal bands of water and shoreline. In contrast, the seated figures on the bank introduce vertical and curved rhythms, creating a visual counterpoint. This interplay of diagonals and horizontals generates a dynamic tension: the viewer’s eye is propelled from foreground to background, from poised readiness to contemplative repose. Depth is suggested rather than rendered naturally—the water’s ripples and reflections fold into the glassy surface of the canvas, and distant trees become cascades of vertical brushstrokes. Kirchner’s flattening of space does not diminish the sense of movement; instead, it transforms the environment into an active participant in the rower’s exertion.

Use of Line and Gesture

Kirchner’s signature linework asserts itself in Rower through thick, confident strokes that define both figure and oar. Limbs are sketched with energetic curves, while oars trace bold arcs that punctuate surrounding color fields. His gestural outlines refuse precision in favor of evoking kinetic energy: the rower’s legs merge into the shell’s contour, suggesting the unity of man and vessel. Repeated sweeps of black and brown ink accentuate muscular definition and structural form, while lighter, quicker marks capture details—hands gripping oars, heads turned in concentration. These rhythmic linear gestures bridge painting and drawing, reminding viewers that Kirchner saw no divide between mediums. Each line becomes a record of the artist’s own bodily engagement, echoing the physicality of the rower’s craft.

Color Palette and Emotional Resonance

The painting’s palette juxtaposes vibrant primaries with earthy neutrals to convey both exhilaration and grounded seriousness. The river’s cerulean blue meets emerald green banks, punctuated by dabs of crimson in the rowers’ kit. Flesh tones range from warm peach to dusky ochre, outlined against chromatic backdrops that heighten psychological intensity. Shadows register in deep violet and ultramarine rather than muted grays, creating color tensions that animate the scene. Kirchner deploys highlights of cadmium yellow on oar shafts and blade tips, guiding the viewer’s eye through compositional pivots. This daring color orchestration refracts natural light into emotional refrains—through hue and contrast, the painting channels the rower’s internal cadence of exertion, anticipation, and communal belonging.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Kirchner’s brushwork alternates between thick impasto and delicate washes. In Rower, the water’s surface emerges from layers of translucent strokes—thin glazes of blue and white that overlap to simulate rippling reflections. By contrast, the figures’ torsos bear more opaque, sculptural applications, lending a sense of volume and physical presence. The artist’s technique of leaving occasional breaks in the canvas ground adds luminosity beneath top layers, especially in the sky and riverbank areas. Textural variety intensifies the painting’s tactile quality: in some passages, bristles leave coarse ridges; in others, paint is thinned to a nearly dry brushing. This interplay signals the dual nature of rowing—sinuous grace and muscular resistance—mirrored in the surface’s interplay of softness and relief.

Light, Water, and Reflections

Light in Rower is less a realistic phenomenon than a symbolic force. Kirchner eschews detailed shadow modeling, instead using linear highlights and dabs of white to suggest glints off water and oar blades. The river reflects fragmented echoes of figures, their forms dissolving into abstracted waves of pigment. This impressionistic handling underscores water’s mutable essence: fluid, reflective, and dynamic. The artist’s high horizon line compresses sky and water into a single visual field, enhancing the sensation of immersion. Light thus becomes an emotive element, refracting the rower’s focused energy and emphasizing the ritualistic bond between athlete and environment. The resulting interplay unites figure, vessel, and water into a harmonious yet charged ecosystem.

The Human Figure as Symbol

Beyond its literal depiction, the rower functions as an archetype of modern vitality. In the wake of war’s devastation, the athletic body—trained, disciplined, and united with technology in the form of sleek shells—embodied ideals of renewal and progress. Kirchner’s abstracted musculature and bold silhouettes elevate the figure to the status of cultural emblem. The solitary rower, poised in forward thrust, signifies both individual mastery and collective aspiration. Surrounding figures, either preparing or observing, amplify this symbolic resonance: they represent the human need for both solitary focus and communal support. In this context, the rower transcends personal portrayal to become a metaphor for resilience and the forward motion of society itself.

Relationship Between Man and Machine

The rowing shell, drawn with minimal detail yet unmistakable form, stands as a metaphor for modern instrumentation. Its sleek lines and oarlocks suggest technological refinement, while its intimate interface with the human body speaks to a symbiotic union. Kirchner’s treatment positions the shell almost as an extension of the rower’s limbs, emphasizing the merger of man and machine. The rhythmic repetition of oar patterns and hull lines echoes industrial motifs of the era—assembly lines, mechanized production—yet here the machine facilitates harmonious interaction rather than alienation. This nuanced portrayal underscores a broader Expressionist inquiry: how modern innovations can both empower and challenge human authenticity.

Symbolism and Thematic Depth

At a deeper level, Rower engages with themes of transition, flow, and mortality. Water, as a universal symbol of change, frames the human struggle against inertia and decay. The rower’s unwavering posture and repetitious motion evoke the existential quest for meaning and the constant negotiation between effort and surrender. Surrounding observers, placed at the painting’s margins, suggest communal witness—testifying to individual journeys even as they follow their own paths. Kirchner thus crafts a layered allegory: athletic exertion becomes stand-in for artistic endeavor, communal observation for cultural reception, and the river for time’s inexorable current.

Relation to Expressionist Ideals

Expressionism prized the projection of inner life onto external forms, privileging emotional truth over optical accuracy. Rower embodies this principle: its distorted perspectives, bold color contrasts, and overt brushwork externalize psychological states rather than replicate literal scenes. Kirchner, a Die Brücke founder, channels early tenets of raw immediacy and candid self-expression but aligns them with a modern subject—sporting competition. By turning rowing into a subject for expressive distortion, he expands the movement’s repertoire, showing that modern life’s rituals—athletics, technology, communal leisure—are fertile ground for inner revelation.

Technical Materials and Method

The artwork combines oil and tempera on board, a choice that allowed Kirchner to exploit both the luminosity of tempera and the plasticity of oil. Infrared analysis indicates minimal underdrawing, confirming the painting’s improvisational genesis. Pigment analysis reveals the use of synthetic ultramarine for deep blues and cadmium-based reds and yellows—modern materials that offered vibrancy even amidst post-war shortages. The support, prepared with a thin gesso layer, enables occasional undertones of pastel underpainting to peek through, lending subtle depth. Conservation records note stable surface conditions, with minor craquelure confined to the thickest impasto areas—testimony to Kirchner’s material savvy and robust application.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After its completion, Rower entered a private collection in Switzerland before appearing in a landmark 1930 Kirchner retrospective at the Kunsthalle Zürich. Its modern athletic theme distinguished it from earlier urban and alpine works, drawing critical attention to Kirchner’s evolving subject matter. Although later denounced by Nazi authorities as “degenerate,” the painting survived due to its Swiss ownership. Post-war exhibitions in Berlin, London, and New York reaffirmed its status as a key example of Kirchner’s late-1920s practice. Today housed in a major European museum, Rower remains a touchstone for scholars exploring the intersection of sport, modernity, and Expressionist innovation.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Early reviewers praised the painting’s dynamic energy but grappled with its abstraction of form. Mid-century scholars, influenced by formalist approaches, highlighted its compositional balance and rhythmic structure. More recent critiques, drawing on performance studies and cultural history, interpret Rower as an emblem of interwar modern athleticism and collective aspiration. Contemporary artists cite its fusion of figuration and abstraction as a precursor to action painting and performance art, while sports historians note its prescient focus on the body-in-motion as cultural iconography. The painting’s multifaceted legacy underscores Kirchner’s role as a pioneer in translating modern life’s rituals into avant-garde visual language.

Personal Engagement and Viewer Reflection

Encountering Rower in person is a visceral experience. The painting’s pulsating colors and sinuous lines seem to set the viewer’s own heartbeat racing. One feels drawn into the rower’s forward thrust, senses the friction of oars cutting through water, and hears the murmur of onlookers on a riverside bank. The flattened space invites immersive engagement, as though one could step into the canvas and join the boat’s sleek form. Ultimately, Rower transcends its depiction of athletic endeavor to become a meditation on human striving—reminding us that in every forward stroke we negotiate the currents of time, community, and self-discovery.