Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

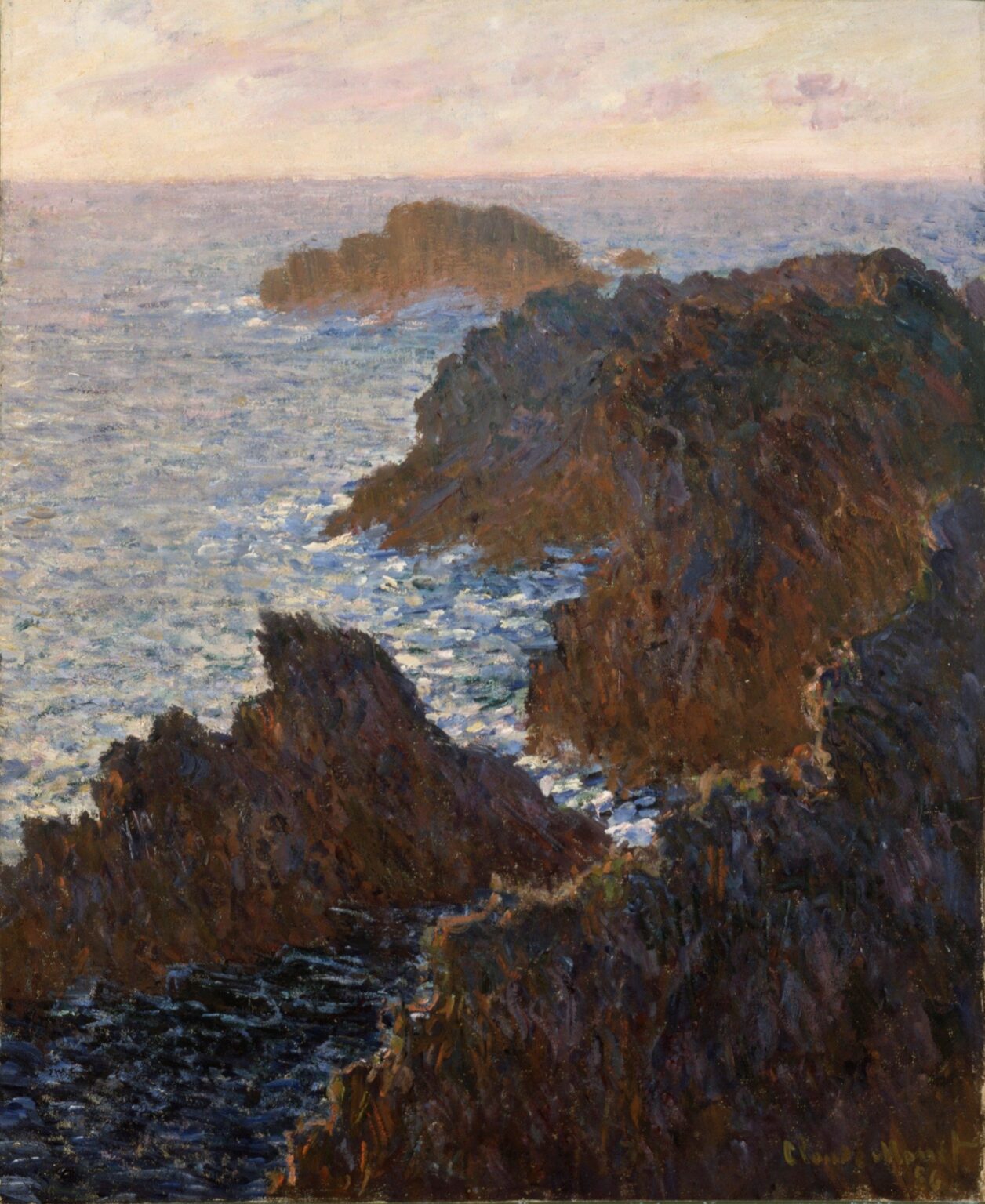

Claude Monet’s Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois (1886) stands as a vivid testament to his adventurous plein-air explorations on Brittany’s rugged Atlantic coast. Eschewing the cultivated gardens of Giverny, Monet ventured to Belle-Île-en-Mer in the summers of 1886 and 1887, seeking to capture the untamed interplay of rock, sea, and sky. In this dramatic canvas, wind-lassed waves crash against jutting headlands, while sunlight fractures across crystalline water. Through a masterful fusion of color, texture, and composition, Monet transforms geological grandeur into a living symphony of light and movement. This analysis dissects how Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois embodies Monet’s mature Impressionist vision, his technical innovations, and its enduring influence on modern landscape painting.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1886, Monet was already celebrated for his revolutionary studies of light on urban and rural subjects—from Argenteuil’s riverbanks to Rouen Cathedral’s façades. Yet his sojourn to Belle-Île represented a bold departure. Alongside contemporaries like Paul Gauguin and Armand Guillaumin, Monet embraced the island’s wild topography, where sheer cliffs and Atlantic storms tested his plein-air resolve. Port-Domois, with its narrow inlets and crystalline coves, offered a dynamic stage for Monet’s investigations into the shifting effects of sunlight and shadow on rock and water. Painting directly on location, often perched on precarious ledges, he confronted elemental forces head-on—yielding canvases that pulse with immediacy and elemental drama.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Monet structures Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois around a diagonal thrust that carries the viewer’s gaze from the lower left foreground up toward the distant horizon at the upper center. The rocky promontories dominate the right two-thirds of the canvas, their faceted surfaces rendered through interlocking strokes of ochre, pink, violet, and deep blue. Water carves sinuous channels between these masses, its surface animated by sunlit sparkles. In the background, the sea stretches to a low, undulating horizon, where pale pink and lavender clouds hover. This compositional arrangement—bold rock formations contrasted with an expansive seascape—establishes both monumentality and depth, underscoring the environment’s vast scale.

Plein-Air Technique and Monet’s Materials

Monet’s direct-to-canvas approach on Belle-Île required portability and speed. He employed a sturdy but lightweight easel and pre-primed canvases, working with a restrained palette enriched by newly available synthetic pigments—cadmium reds and yellows, cobalt blues, and viridian green. These brilliant hues allowed him to capture the Atlantic light’s intensity without muddying. He applied paint in thick impasto for rock textures and thinner glazes for water and sky, often returning multiple times to refine effects as clouds shifted or tide patterns changed. This layered practice lent the painting both textural depth and spectral luminosity.

Light and Color: Optical Vibrancy

At the heart of Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois lies Monet’s treatment of light as a sculptor of form. Sunlit facets of the cliffs blaze with warm cadmium yellow and rose madder, while shadowed crevices recede into mixes of ultramarine, violet, and burnt sienna. The water, reflecting this chromatic interplay, glimmers in a matrix of emerald, cerulean, and flecks of titanium white. Monet deliberately juxtaposes complementary strokes—warm ochre against cool blue, pink accents amid green ripples—relying on the viewer’s eye to blend them into radiant optical effects. This dynamic color harmony captures both the solidity of rock and the fluidity of sea within a unified field of light.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Monet’s brushwork here is unapologetically varied, each gesture tailored to the motif at hand. Rock faces emerge from layered, jagged strokes—short, prismatic dabs that mimic the cliff’s granular textures. Water is indicated by horizontal, rhythmic sweeps that convey current and reflection, while thinner, more translucent brushmarks in the sky capture drifting high-altitude clouds. Instances of wet-on-wet application allow pigments to mix directly on the canvas, producing subtle gradations and color intersections. The tactile surface—impasto ridges on rock, smooth overlays on the sea—engages viewers not only visually but almost physically, evoking the roughness of granite and the cool spray of surf.

Atmospheric Perspective and Depth

Despite the painting’s richly textured foreground, Monet achieves convincing spatial recession through atmospheric perspective. The nearest rocks are delineated crisply with high-contrast strokes, whereas the midground cliffs soften into cooler, more muted tones. The distant horizon and sky merge in pale washes of pink and blue, their forms barely distinguishable. This graduated fading replicates natural vision: near objects appear clear and saturated, while distant ones blur and cool. Monet thus anchors his bold brushwork within a coherent three-dimensional space, guiding the viewer from the tactile immediacy of the rocks to the horizon’s serene distance.

Geological and Ecological Detail

Monet’s depiction of Belle-Île’s geology is both scientifically astute and poetically expressive. The cliff formations—likely Devonian or Precambrian schist and sandstone—are suggested through layered strokes of rust red, violet, and umber, reflecting mineral compositions and weathering patterns. Sparse patches of vegetation—lichen, sea grasses, coastal heath—are evoked by brief green and yellow flicks, hinting at the island’s hardy flora. Where the water meets stone, Monet captures wave tips in sharp white, while the deeper channels retain a verdant translucence. These ecological nuances lend the work not just visual interest but environmental authenticity.

Emotional Resonance and Sublime Majesty

Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois transcends mere topographical study to evoke an emotional response akin to the Romantic sublime. The sheer scale of rock meeting sea, the suggestion of wind-hurtled clouds, and the interplay of light and shadow combine to inspire awe. Monet’s energetic brushwork amplifies this effect, as if the canvas itself quivers with elemental forces. This sense of wonder and humility before nature’s power aligns Monet with both earlier Romantic painters and with Impressionism’s modern psyche—celebrating the sensory immediacy of experience while acknowledging nature’s grandeur.

Monet’s Belle-Île Sojourn and Artistic Evolution

The Belle-Île period marks a critical juncture in Monet’s career: a time when he expanded his subject repertoire to include truly wild landscapes, pushing his plein-air methods to their limits. Works like Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois reveal a painter increasingly comfortable with abstraction—breaking forms into fields of color and light rather than adhering to strict realism. These experiments presage Monet’s later Giverny water lily series, where form dissolves almost entirely into chromatic rhythms. Belle-Île thus served as both physical and conceptual training ground, fostering Monet’s transition from observational naturalism toward pioneering modern abstraction.

Technical Studies and Conservation Insights

Scientific analysis of Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois underscores Monet’s layered process. Infrared reflectography reveals initial charcoal outlines mapping the most prominent rocky forms. Pigment sampling identifies cadmium-based reds and yellows alongside traditional earth pigments, confirming Monet’s embrace of new materials. Cross-section studies show a warm ochre ground beneath successive layers of colored brushstrokes, imparting an inner glow. Conservation efforts have focused on stabilizing heavy impasto areas vulnerable to flaking and removing discolored varnish, thereby reviving the original chromatic intensity and clarifying Monet’s subtle color transitions.

Reception and Exhibition History

Monet’s Belle-Île paintings were first exhibited in Paris in spring 1887, eliciting admiration for their daring subject matter and vivacity of color. Critics hailed their fresh vision of coastal scenery, though some traditionalists lamented the perceived “unfinished” brushwork. Over subsequent decades, as Impressionism gained canonical recognition, Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois emerged as a touchstone of Monet’s adventurous spirit. It passed through prominent private collections before entering a major museum, where it continues to be celebrated in retrospectives and scholarly surveys as a highlight of late 19th-century landscape painting.

Influence and Legacy

Monet’s Belle-Île canvases influenced both his peers and later generations. Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh drew inspiration from Monet’s vibrant coastal palettes and expressive brushwork. In the 20th century, artists exploring abstraction—Wassily Kandinsky, Mark Rothko—acknowledged Monet’s role in freeing paint from descriptive constraint. Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois remains a vital reference for plein-air painters worldwide, illustrating how direct engagement with primeval landscapes can yield works of enduring power and innovation.

Conclusion

In Rocks at Belle-Île, Port-Domois, Claude Monet melds geological grandeur, oceanic energy, and painterly daring into a unified vision of natural splendor. His mastery of color, texture, and composition transforms rugged cliffs and churning seas into a luminous spectacle of light and movement. As both document and poetic evocation, the painting exemplifies Impressionism’s radical departure from studio conventions and heralds the advent of modern approaches to landscape. Over a century later, Monet’s Belle-Île masterpiece continues to captivate, inviting viewers to share in the exhilaration of standing upon the rocks and feeling Atlantic winds kindle the soul.