Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

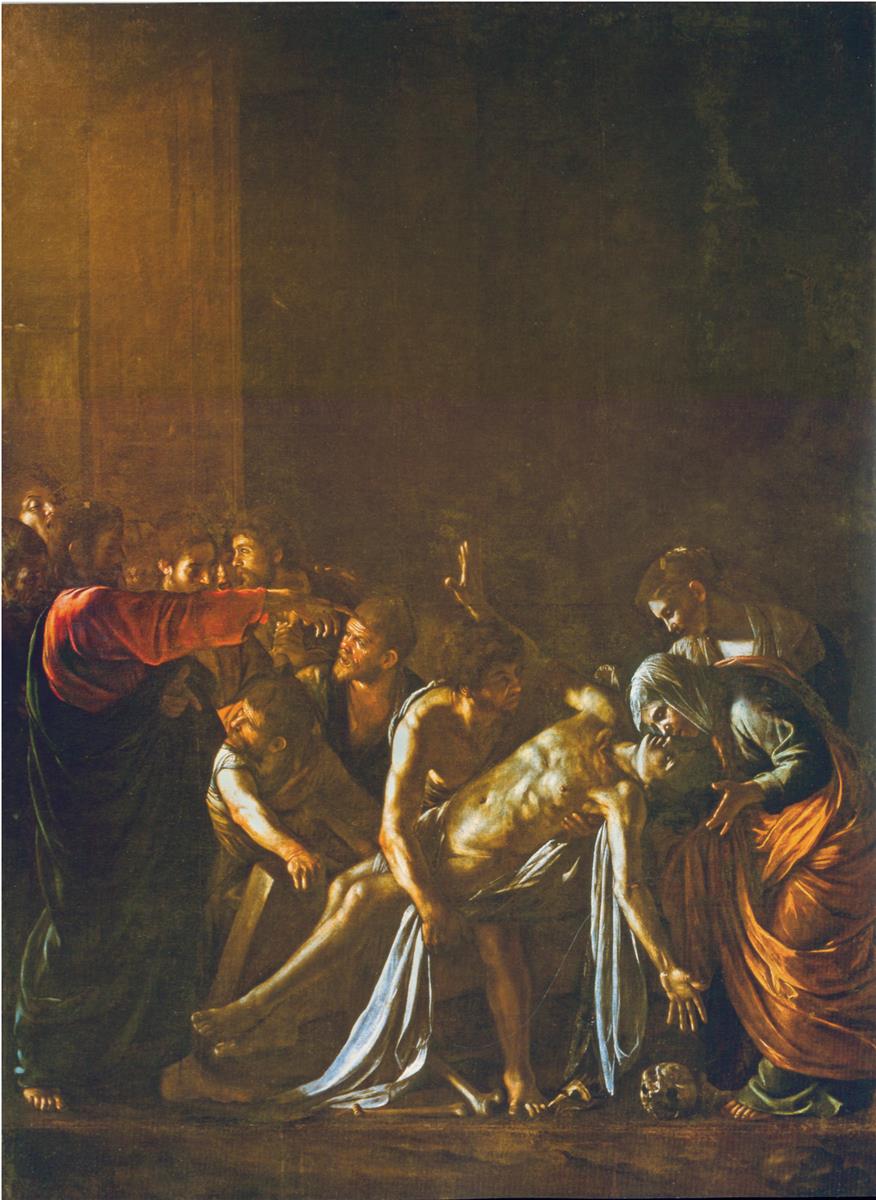

Caravaggio’s “Resurrection of Lazarus” (1609) condenses one of the Gospel’s most dramatic miracles into a charged moment of command, doubt, and awakening. Painted in Messina during the artist’s late Sicilian period, the canvas transforms a familiar story into a visceral encounter with flesh and light. The miracle does not unfold as a distant spectacle. It happens at arm’s length, in a dark room crowded with laborers’ bodies, where Christ’s outstretched hand sends a beam of illumination across a corpse that is already beginning to rise. Caravaggio refuses to treat the scene as an allegory. He treats it as an event. In doing so he makes the Resurrection not an abstract promise but an experience of light cutting into darkness and of breath returning to weight.

Historical Context and Commission

Caravaggio arrived in Sicily after turbulent years that included the Roman homicide that exiled him, commissions and clashes in Naples and Malta, imprisonment, escape, and a desperate desire for pardon. Messina welcomed him with two great altarpieces: the “Adoration of the Shepherds” and the “Resurrection of Lazarus.” The patronage of the local faithful and clergy gave the artist a new stage for his uncompromising naturalism. Sicily’s Capuchin and Jesuit circles favored images that taught clearly and moved the heart. Caravaggio’s art, with its insistence on ordinary faces and tactile truth, matched those aims perfectly. In that climate the raising of Lazarus—an image of hope for the poor and the grieving—became not merely a narrative but a pastoral instrument, intended to be understood by dockworkers and merchants as readily as by nobles.

The Moment Chosen

The painting fixes the instant between command and compliance. Christ has spoken; Lazarus has begun to respond; the onlookers vacillate between recoil and astonishment. Caravaggio forgoes the afterglow of triumph and captures the raw hinge of transformation. Everything in the composition registers the tension of that hinge. Christ is not a distant halo but a man who steps forward, arm extended as if issuing an order on a battlefield. Lazarus is not yet fully upright; his torso arches as though the body is remembering how to live. The gap between the two hands—Christ’s commanding, Lazarus’s opening—is the painting’s theological space, a current of force made visible.

Composition and the Architecture of Bodies

The rectangle is bisected diagonally from the glowing wall at upper left to the cluster of figures at lower right. Caravaggio gathers nearly all the action into a dense knot of bodies that crowd the foreground. The enormous empty field above them, barely described by architectural planes, makes the miracle feel small and human in a vast, mute world. The left third of the canvas holds Christ and his disciples, compressed into a wedge that points directly at Lazarus. The right two-thirds hold the corpse and mourners. The procession of limbs curves like a wave: a lifting forearm, a turning wrist, a kneeling helper’s shoulder, the arc of Lazarus’s ribcage, the downward sweep of Martha’s drapery. This wave carries the eye toward the center where the old drama—death resisted—takes physical form.

Tenebrism and the Physics of Revelation

Caravaggio’s light is not atmospheric. It is directional and judicial, a beam that reveals and divides. The main source falls from the upper left, crossing Christ’s sleeve, striking the faces of the nearest disciples, and igniting the pale terrain of Lazarus’s chest and arms. Darkness absorbs the extraneous. The background architecture becomes a faint grid; distant faces recede into brown shadow; the edge of the room dissolves. In that way the light renders the miracle as empirical fact. You do not see the idea of resurrection. You see exposure where darkness had ruled, and you register its truth in the way skin takes on color, in the catchlight at the rim of an eye, in the slack hand that begins to curl.

Christ’s Gesture and the Language of Command

Christ is almost entirely defined by gesture. His red sleeve and dark mantle form a powerful block of color, but it is the arm—extended, palm forward, fingers aligned—that speaks. Caravaggio’s Christ is not ecstatic; he is authoritative. The hand reads like a legal verdict. It is also mimetic: viewers can imitate it with their own bodies, sensing in their muscles the firmness required to project conviction. Around Christ, the disciples gather with faces lit in partial profile, their expressions a mixture of wonder and attention. They are witnesses and transmitters, men who will carry this gesture into the world.

Lazarus as a Study in Reanimation

Lazarus lies nearly horizontal across the foreground, his head supported by a woman who leans to kiss his brow, his torso arced as the breath returns. Caravaggio paints the body with merciless accuracy: the pallor of the belly, the slackness of the extremities, the weight of the arm that still falls toward the skull and stones at the lower edge. Yet the figure is not inert. One hand opens toward Christ, fingers splayed as if feeling the air; a knee bends; the tautness along the ribcage implies muscular awakening. The miracle registers not as a melodramatic leap to life but as a sequence of physiological cues. The painter, trained by observation and by his own interest in anatomy, understands that convincing resurrection must first convince the eye.

Mary, Martha, and the Grammar of Grief

The women in the right foreground—traditionally read as Mary and Martha—anchor the human response. Martha gestures with a splayed hand, her body thrown forward, her drapery alive with folds that catch the light. Mary, closer to Lazarus, cradles her brother’s head with a tenderness that suffuses the scene with familial truth. Caravaggio does not romanticize their faces. He gives them the solid features of working-class women and thereby makes grief legible without affectation. The sisters become the hinge between death and life, between the command of Christ and the body’s obedience.

Witnesses, Doubters, and the Crowd

Behind the central figures a small assembly of men lean and crane to see what is happening. Their heads repeat the compositional arc, each profile slightly overlapping the next like a frieze of curiosity and uncertainty. One man raises a hand in defensive shock; another bends to help lift; others peer past shoulders with eyes narrowed. Caravaggio uses them as instruments of emphasis. They form a chorus that does not sing but concentrates, a human amplification of the miracle’s significance. Because they look not at us but at Lazarus, they direct our attention, acting as guides within the drama.

Symbols on the Floor and the Memento of Death

At Lazarus’s feet lie stones, dirt, and a skull barely touched by light. Caravaggio seldom resorts to explicit symbolism, yet here the skull functions as a quiet memento mori. It belongs to the cave of burial and to the human condition at large. Its placement at the bottom edge, almost tripped over, keeps the painting from triumphant simplicity. Even as life returns, death is acknowledged as the ground on which the miracle stands. The still slack hand nearly grazes it, as if the resurrected man must pass his fingers over the fact of mortality on his way back to breath.

Space, Stage, and the Sense of Proximity

The depth is shallow. The figures push forward until their feet nearly share our floor. The arch of Lazarus’s body touches the picture plane; you feel you could slide a hand beneath his shoulder to help lift. That sense of proximity is not incidental. In a church setting it would invite worshippers to identify with the mourners, to take part in the raising by leaning forward, by praying, by accepting the command implicit in Christ’s gesture. The architecture at the left is blur and plane, not destination, which means that the miracle’s space is our space, the place where viewers stand.

Naturalism and the Ethics of Visibility

Caravaggio’s naturalism often scandalized contemporaries who preferred idealized saints. In Messina he doubles down on the ethic that the sacred must be believable to the eye of the poor. Skin looks like skin; the dead look dead; the helpers have the thick hands of laborers; the fabrics hang with weight. This ethic is not mere style. It is a theological claim: if the divine acts in the world, the world will bear witness in its ordinary materials. Faith becomes a way of seeing accurately. The painting teaches that lesson by demanding attention to specificities—the fold in a drape, the tension of a tendon, the shadow under a heel.

The Late Style and the Shadow of Exile

By 1609 Caravaggio’s life was marked by flight and danger. In his late works the light grows more austere, the settings emptier, the figures more tightly compressed. The “Resurrection of Lazarus” shares these traits. The darkness is not menace for its own sake; it is the pressure of a world closing in, a world from which revelation must be carved. The painter’s personal desperation may have sharpened his empathy for scenes in which hope arrives late and abruptly. His Lazarus rises not in a garden but in a bare room. The miracle is not ornamented; it is necessary.

Comparisons with Earlier Resurrection Imagery

Earlier Italian treatments of Lazarus often include expansive landscapes or architectural vistas that situate the miracle within civic order and natural beauty. Caravaggio discards these comforts. He chooses the claustrophobic intensity of a chamber where bodies crowd one another and air feels scarce. In doing so he moves the subject from spectacle to experience. The absence of grand scenery makes the divine intervention feel closer to lived crisis. The painting thus contributes to a broader Baroque shift in which sacred episodes are brought into the viewer’s immediate space to provoke participation rather than distant admiration.

Light as Word and Breath

The Gospel tells that Christ called Lazarus by name. Caravaggio translates that call into light. The beam that touches Lazarus reads as a physical analogue of the creative Word: a force that both addresses and transforms. At the same time, the light delineates the path of breath as it returns—glancing off the ribs, sliding across the throat, warming the cheeks. The painter unites doctrine and physiology by using illumination to stand for both meaning and air. The effect is not allegorical but incarnational. What the mind believes, the body feels.

Gesture as the Engine of Narrative

Every story element is carried by hands. Christ’s hand commands; Lazarus’s hand opens; Martha’s hand pleads; a helper’s hands grip the shroud; a witness’s hand rises to block the shock. Because Caravaggio avoids theatrical facial expressions, the hands carry the drama. They articulate relationships—authority to obedience, grief to consolation, fear to recognition. The choreography of fingers and palms creates a grammar the eye can read instantly, even from across a nave.

The Place of the Painting in Sicilian Devotion

Installed in a church, the canvas would have served preaching and confession. The faithful could point to Martha’s gesture or to the slack hand near the skull and find in them images for their own prayers. The raising of Lazarus, celebrated as proof of Christ’s dominion over death, becomes in Caravaggio’s treatment an encouragement to those feeling entombed by poverty, illness, or sin. The painting thus functions as a tool of consolation and exhortation: if light can grip even this heavy body, it can find yours.

Technique, Surface, and the Evidence of the Brush

The metallic highlights, the wet gleam along Lazarus’s abdomen, the leathery tones of the workers’ arms reveal Caravaggio’s mastery of oil’s capacities. He moves between thinly scumbled passages that leave the canvas’s grain breathing and denser, glazed zones that lend flesh its interior warmth. The brush is mostly restrained, subordinated to the illusion, yet here and there a brisk stroke along a knuckle or a fold flashes like a signature. The surface feels worked with speed and certainty, as if the painter trusted that the truth of light on matter would carry the emotion more reliably than elaborate finish.

Reception and Afterlife

The Messina altarpieces influenced painters in Sicily and southern Italy who pursued tenebrism and concentrated devotional realism. The “Resurrection of Lazarus” in particular offered a model for turning biblical rupture into human-scale drama. Later Baroque artists amplified its lessons, sometimes clothing them in greater theatricality, sometimes preserving its starkness. For modern viewers the picture remains startlingly contemporary in its refusal to sentimentalize either death or miracle. It insists that before a claim can comfort it must convince. It convinces by showing what resurrection would look like in a room like ours.

A Contemporary Reading of Hope

The painting speaks powerfully to a world acquainted with loss. Caravaggio does not erase the signs of death; he forces us to look at them—the skull, the colorless hand, the effort of the men who lift. Hope in this image is not denial. It is a command answered. The miracle dignifies those who labor and those who mourn by involving them. The resurrected man does not spring up alone. He is helped by friends, steadied by sisters, called by a voice. In that sense the picture offers a social vision as well as a spiritual one: life is restored in community, under a word that summons and a light that makes room.

Conclusion

“Resurrection of Lazarus” stands among Caravaggio’s deepest meditations on power and mercy. Composition, light, and the sheer weight of bodily truth converge to make the miracle feel both extraordinary and credible. The emptiness above the figures underscores human smallness; the beam across Lazarus’s chest announces significance; the hands write a story of command, assistance, and awakening. In Messina’s dark chapel the canvas would have met sailors and widows and children with an image that does not patronize their experience of grief. It tells them that the voice that calls life back does so in rooms like theirs, onto floors like theirs, through hands like theirs. Few paintings render theology so physical or give hope such muscular form.