Image source: wikiart.org

A Garden Seen Through Another Painter’s Eyes

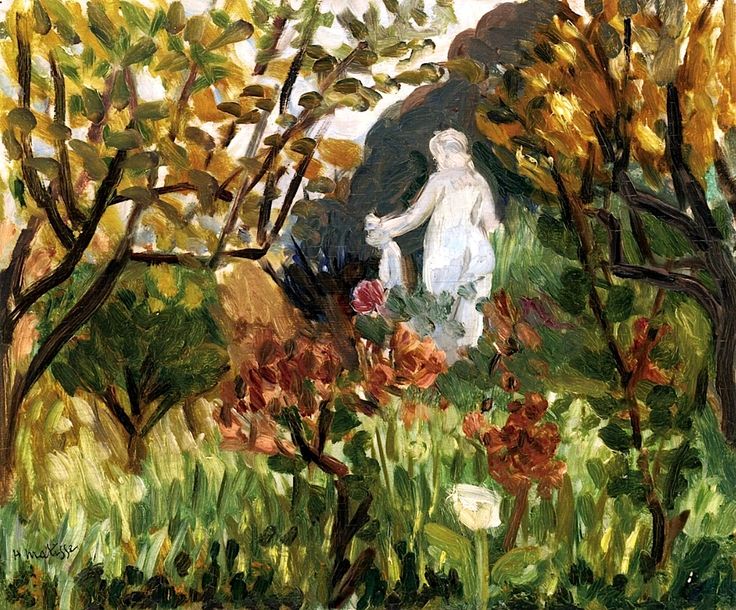

Henri Matisse’s “Renoir’s Garden” (1917) is a compact, exuberant landscape that feels at once observational and homage. In a shallow, leafy space built from quick strokes of yellow-green, olive, and rust, a single pale figure stands near the center like a small column of light. The title points us toward the picture’s double subject: a garden Matisse saw while visiting Pierre-Auguste Renoir in the south of France, and the older painter himself, evoked indirectly through palette, touch, and the sensuous fullness of foliage. The canvas reads as a conversation in paint—Matisse answering Renoir with his own syntax of contour and color, compressing a dense world into a few decisive relationships.

Setting and Motif: A Garden as Refuge and Studio

The year 1917 matters. France was deep in the First World War, and Matisse, like many artists, sought steadier climates for body and mind. He traveled repeatedly to the Mediterranean coast and visited the ailing Renoir at Les Collettes in Cagnes-sur-Mer. There, gardens were not merely scenery; they were lived spaces, outdoor studios, and repositories of light. “Renoir’s Garden” carries that sense of refuge. The foliage forms a leafy amphitheater around a pale classical figure—likely a garden statue—so that nature becomes a room, and the statue becomes both subject and measure of the painter’s touch. The motif allows Matisse to braid together his admiration for Renoir’s sensual color with his own wartime discipline.

A Composition Framed by Trees and Driven by Triangles

Matisse organizes the picture with two strong edge trees that act like curtains, their dark limbs veering inward to frame the view. Between them, shrubs and blossoms form diagonal bands that rise toward the central figure. The statue and the dark, shrub-covered mound behind it make a soft pyramid, a classic compositional device that steadies the riot of small strokes in the foreground. Look longer and you sense a figure-ground rhythm: trees push forward as solid calligraphy; light skips between leaves; the central whites pull you inward. It is a composition that delivers movement and pause in the same breath.

Color as Climate: Warm Greens, Sunlit Yellows, and Autumn Rusts

The palette sings a southern register without turning gaudy. Fresh sap and olive greens construct the field and shrubs; yellows tip the leaf edges into sun; ochres and umbers deepen trunks and undergrowth; a scattering of brick reds marks flowers and warm soil; and the statue is kept in high, cool values that read as stone bleached by light. Matisse rations blue to the shadows of the central mound, letting that coolness push the warm foliage forward. Because the colors are tuned rather than saturated, they function as climate—an enveloping air of late summer or early autumn—rather than as isolated signals.

Brushwork You Can Feel

The painting is a festival of touch. Short, comma-like strokes feather the leaves; longer, ribboning passes sweep up the trees; loaded daubs of red and white stand proud for blossoms and sunstruck petals; and the statue’s body is blocked with a few thick, milky planes. Matisse varies pressure so bristles occasionally scratch through wet paint, letting underlayers breathe. This variety keeps the small canvas lively and recalls Renoir’s own broken touch—yet Matisse’s strokes are more calligraphic and structural, their directions orchestrated to guide the eye rather than merely to mimic shimmer.

Black Contour as a Modern Answer to Impressionist Light

Around 1916–1917, black reenters Matisse’s palette as a constructive color. Here, in “Renoir’s Garden,” it appears as emphatic darks outlining trunks and branches. Those assertive lines are Matisse’s reply to Impressionism’s refusal of contour. He accepts Renoir’s appetite for color and light but adds a scaffolding of dark strokes to keep the composition from dissolving into pure atmosphere. The hybrid language—Renoir’s shimmer plus Matisse’s calligraphic structure—feels perfectly suited to a garden that is both wild and tended.

The Statue as Axis, Memory, and Mirror

That pale figure near the center may be a sculpture in Renoir’s garden; it also functions as a memory of Renoir’s lifelong devotion to the human figure. By keeping the statue cool and stony—high grays and milky whites—Matisse sets it apart from the warm, nervous field of vegetation. The figure is not modeled in detail; it’s stated in planes, with a small gesture of arm and hand that seems to greet the blossoms. The statue mirrors Matisse’s purpose: to place human presence within nature without overpowering it, to acknowledge tradition without copying it.

Light as an Even, Democratic Envelope

Illumination in the picture is broad and evenly distributed, more like a climate than a spotlight. Whites wink out across the foliage—on leaves, petals, and the statue—creating a rhythm of glints that carry the eye. Shadows are cool and transparent rather than brown and heavy, especially in the central mound and under the trees’ canopies. This even light supports Matisse’s lifelong aim for balance and serenity: the eye moves without interruption, and no corner of the picture hardens into theatrics.

Space by Overlap, Value, and Color Temperature

Matisse builds space without linear perspective. Foreground grasses overlap mid-ground flowers; the warmest greens ride in front while cooler, bluish greens recess; the dark mound behind the statue steps the eye backward; the bright gaps at the top—small wedges of sky—unlock the depth. This is Renoir’s depth transposed into Matisse’s voice: layers of vegetation that invite the viewer to look through rather than into a rigid box. The effect is more like walking in a garden than viewing a stage.

The Eye’s Route Through the Picture

The composition proposes a rewarding itinerary. Most eyes catch the statue first, dazzled by its pale value against the dark mound. From there they slide down the arm to the cluster of ruddy blossoms at the figure’s feet, weave through the vertical grasses, bounce along the red-orange clumps at left and right, and finally climb the dark trunks framing the scene. As the eye approaches the top, it meets the bright sky peeking through leaves and loops back down to the statue again. Every stage in this route is punctuated by contrasts—cool against warm, light against dark, crisp calligraphy against soft daubs—so the circuit never grows dull.

Renoir’s Influence Made Visible

The painting’s title gives permission to look for Renoir in the work, and he is everywhere. The luscious foliage, the sensual compression of depth, the sense that the air itself is gently stroked—these are Renoir traits. Yet the difference is clarifying. Renoir’s figures often melt into atmosphere, while Matisse’s statue keeps its silhouette; Renoir lingers in rosy flesh and satin fabric, while Matisse delights in the music of greens; Renoir distributes glints like pearls, Matisse deploys white and black as structural notes to stabilize improvisation. “Renoir’s Garden” is not pastiche; it is filial conversation.

Wartime Discipline: Clarity Over Spectacle

In 1917, Matisse’s palette had tightened from the blazing Fauvism of a decade earlier. He was pursuing clarity through reduction—fewer elements, stronger relations. This canvas shares that ethic. There is no elaborate sky, no distant architecture, no narrative staffage. The painting proposes that a garden—leaves, trunks, grass, a single pale figure—is sufficient to carry mood and meaning when relations are true. That wartime discipline produces a poise that the viewer can feel, a steadiness of tempo that settles the nervous system.

Material Facts: A Surface That Refuses Gloss

Up close, the painting’s body tells its own story. The paint is neither glassy nor calcified; it rides the canvas with small ridges at leaf edges and flattening swathes in the mound’s shade. Direction changes are legible where Matisse reinscribes a branch with a surer stroke or pushes a blossom a notch redder to pop against green. The surface refuses the glossy finishing that would dissolve process into effect. You see how the garden was found and fixed, not merely pictured.

The Garden as a Studio of Looking

For Matisse, gardens were laboratories where he could test the grammar of painting against the abundance of nature. In “Renoir’s Garden,” that laboratory produces several lessons. First, variety can be achieved through direction rather than through a riot of hue. Second, whites need not be reserved for highlights alone; they can act as living notes within foliage and as structural anchors in the statue. Third, black, properly used, keeps nature’s chaos legible without making it brittle. The result is a garden that feels inevitably itself and also like a composed score.

A Dialogue with Sculpture and the Antique

By making a statue the central figure, Matisse quietly invokes older dialogues—between painting and sculpture, between the living model and the antique. The statue is the garden’s still point, a memory of the classical body in a living environment. It belongs to a recurring Matisse motif: placing a pale figure within a warm, patterned world—iron balconies, tiled floors, floral textiles—so that art and life are staged together. Here the marble form becomes a measure of time: nature cycles; stone endures; painting mediates.

Emotional Temperature: Calm, Generous, and Generative

Despite the abundance of strokes, the painting feels calm. That calm arises from the even light, the complementary anchoring of dark trunks, and the centered, upright statue whose gesture suggests greeting rather than drama. The emotional temperature is generous. This is a garden that opens rather than encloses, a place where color grows rather than argues. In the year it was made, such generosity mattered.

Comparisons with Matisse’s 1917 Landscapes

Viewed alongside other 1917 works—“Chalais Meudon,” “Le Carrefour de Malabry,” or the harbor scenes from Marseille—“Renoir’s Garden” stands out for its density of vegetative marks and its central pale figure. The broader landscapes often rely on big sky zones and long receding paths; here the sky is merely glimpsed between leaves and depth is compact. That compression makes the picture feel bodily, almost tactile, as if the viewer were kneeling in the grass rather than looking out across a field. It also aligns the painting with Matisse’s concurrent studio interiors: a compact world made complete by a few well-balanced forms.

Why “Renoir’s Garden” Still Feels Fresh

The canvas endures because it solves a perennial problem with grace: how to paint the abundance of nature without losing clarity, and how to honor another artist’s spirit without losing one’s own. Matisse does both. He lets Renoir’s affection for garden light guide his palette, while his own calligraphy and discipline keep the scene legible and modern. From across a room the image reads at once—trees, statue, flowers, grasses, sun. At arm’s length the weave of strokes becomes a pleasure in itself, a record of decisions that never harden into manner.

A Closing Reflection on Influence and Invention

“Renoir’s Garden” stages a respectful handoff between generations. Renoir’s sensual Impressionism—air as brushwork, color as flesh—passes through Matisse’s compositional mind and emerges renewed: structurally clear, lyrically painted, and emotionally steady. The small pale statue at the center can be read as a figure of influence, a guardian of tradition within a living, changing world. Matisse neither embalms nor imitates; he cultivates. In that act of cultivation the painting offers what its subject promises: renewal.