Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Nice-Period Portrait Studio

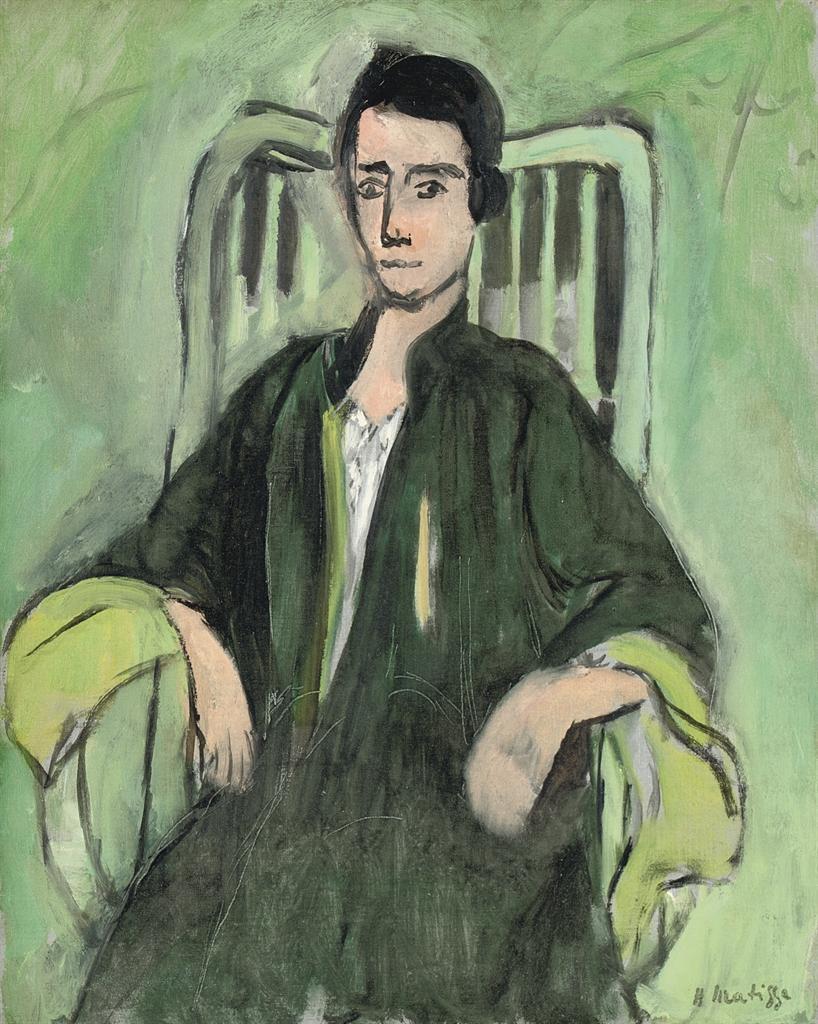

Henri Matisse painted “Renée, Green Harmony” in 1923, during the heart of his Nice period, when he transformed sun-washed rooms on the Côte d’Azur into theaters for color, pattern, and the human figure. After the blazing experiments of Fauvism and the structural rigor of the 1910s, his goal in Nice was a gentler intensity: forms simplified into legible planes, light treated as a continuous veil, and color allowed to carry the emotion of the scene. This portrait fits that program yet retains a bracing directness. The sitter, Renée, anchors the composition from an armchair whose pale rails echo the verticals of a screen; around her Matisse spreads a single dominant climate of green, letting tonal variations of that hue stage the conversation between face, garment, chair, and air.

Composition As A Calm Frontality With Elastic Edges

The structure is frank and frontal. The sitter faces us squarely, shoulders level, hands resting on the chair’s upholstered arms. Matisse crops tight so the figure fills the field; the chair’s uprights frame the head like a light, informal cartouche. Long verticals in the garment pull the eye downward to quiet the breadth of the torso, while the diagonals of the forearms lead outward to the edges and rebound inward again. The composition feels symmetrical without becoming stiff: the head leans a breath to the sitter’s left, one hand opens a little more than the other, and those tiny asymmetries keep lifeblood in the pose. Cropping enhances presence. The viewer senses they are nearly within arm’s length, close enough to register the give of fabric and the weight of the sitter in the chair.

The Green Harmony: A Single Climate With Many Temperatures

Everything here is keyed to green: mint and celadon in the background, olive and bottle green in the robe, yellow-green glints at cuffs and chair arms, and a cool sea-green in the painted rails behind the head. By operating within one chromatic family, Matisse achieves the “harmony” named by the title, but he avoids monotony by modulating temperature and value. Warm greens push forward in the sleeves; cooler, bluer greens withdraw in the backdrop; small, milky greens soften edges where arm meets chair. The flesh emerges not by contrast with black shadows but by the neighborly pressure of these greens; cheeks and hands carry peach and shell-pink notes that glow because the surrounding climate is so consistent.

Drawing Inside The Paint: Contours That Breathe

Matisse’s drawing is carried by the brush, not by a laborious line. The contour of the jaw thickens and thins as it meets the neck; the brow is a confident arc; the nose is a single wedge; the mouth compresses into a small, decided shape. He lets underlying sketch marks and corrections remain as ghost lines, especially in the lower half of the robe, so the surface records thought in motion. Along the cuff and chair arm, he drags a nearly dry brush so that the mark both outlines and textures the form. These living edges keep the portrait from ossifying into a polite likeness; they pull our attention to the act of looking and deciding.

Light As A Continuous Veil Rather Than Spotlight

Illumination arrives as the Nice period’s signature: a soft maritime wash that clarifies form without theatrical highs and lows. Highlights pool gently along cheekbone and the bridge of the nose, but they never flare. Shadows lean blue-green rather than black; under the chin a cool veil separates head from torso without cutting a hard contour. Because light is consistent, color bears the emotional weight. The background’s pale, breathing green reads as air; the darker robe feels dense and proximate; the small whites at collar and cuff give the eye places to rest.

The Chair As Silent Architecture

The high-backed chair performs crucial structural work. Its pale rails echo the vertical thrust of the figure while providing a luminous halo that prevents the dark hair and robe from sinking into the green field. The rounded top slats mirror the arc of the head and shoulders, a repetition that steadies the design. At the lower edges, the broad, cushioned arms receive the sitter’s hands and turn them outward, creating a stable base that balances the portrait’s frontal authority with a relaxed stance.

Garment As A Device For Scale, Rhythm, And Depth

Renée’s robe is more than attire; it is a field for orchestration. A deep central green falls like a curtain, split by a soft vertical slit of lighter value that hints at the white blouse beneath. This slender axis quiets the breadth of the torso and adds a gentle recession into the body. Cuffs roll back in yellowed greens that catch and reflect light, tying the garment to the chair’s pale tones and increasing the range of the green chord. Long, slow strokes describe the fabric’s weight; faint incised lines and rubbed passages suggest folds without fuss. The robe gives Matisse a broad plane on which to demonstrate how modulation within one color can model volume and express calm.

The Face: Masklike Clarity, Human Warmth

Matisse simplifies Renée’s features into firm, readable signs—arched brows, dark almond eyes, a straight nose, and a compact mouth. This masklike clarity does not reduce the sitter to an emblem; it concentrates presence. The face holds the field because it is the warmest and most varied zone in the picture: cool gray shadows near the temple, warmer peaches at cheek and chin, a pinker note in the lips, and small, decisive blacks at eyes and brows. The head’s slight tilt constitutes the portrait’s subtlest drama, a clue that the stillness is lived, not staged.

Space Built By Planes And Overlap

Depth is shallow yet certain. The sitter overlaps the chair, which in turn overlaps the green wall. Value steps down as the picture recedes—dark robe, lighter chair, palest background—so we sense space without any linear perspective scaffolding. Broad brushes knit background strokes into the figure’s contour, keeping the space continuous. The result is an intimacy without claustrophobia: the sitter is close, the room is present, and the air between them is breathable.

Rhythm And Repetition: The Eye’s Loop

Visual rhythms knit the composition. Vertical repetitions in the chairback and robe seams establish a heartbeat. Rounded forms recur at head, shoulders, and cuff rolls. Color motifs cycle: the yellow-green of the cuffs returns in faint background swirls; the deep green of the robe reappears as darker hair; the pale mint of the chair rails re-emerges in the wall’s highlights. The eye travels a loop—face, left hand, cuff, hem, right C-shaped sleeve, up the vertical seam, back to the face—and each pass reveals a new syncopation: a faint scratched line in the robe, a ghost mark on the chair, a cool seam under the jaw.

Material Presence And Tactile Distinctions

The surface is richly varied. In the background, paint is thin and scumbled, letting the weave breathe and creating a granular air. In the robe, strokes are broader and more opaque; bristle ridges catch light, imitating the heft of cloth. Along the cuffs Matisse lays buttery, higher-key greens that stand slightly proud of the surface. In the face, transitions are thinly blended to preserve luminosity. These shifts in handling differentiate air, fabric, wood, and flesh without resorting to literal texture, keeping the painting modern and felt.

Psychology Of Stillness And Authority

Although nothing overtly “happens,” the portrait carries psychological charge. The sitter’s squared shoulders, even gaze, and centered placement communicate self-possession; the soft, rolling cuffs and relaxed hands temper that authority with calm. The green climate adds a restorative mood historically associated with renewal and balance. Matisse does not insert anecdote; instead, he allows color, posture, and proximity to project character—assured, measured, and grounded.

Kinship And Contrast Within The Nice Sequence

Compared to Matisse’s patterned interiors and odalisques of the same years, “Renée, Green Harmony” is ascetic: no carpets, no window vistas, no profusion of motifs. The restraint is instructive. By limiting accessories and committing to one color family, Matisse demonstrates that the Nice grammar—clear planes, even light, drawing inside paint—does not require decorative abundance to sing. The portrait sits alongside his “harmonies” in blue or red as a demonstration of tonal orchestration applied to a living presence.

Lessons In Design: Why The Picture Feels Balanced

The portrait’s balance arises from calibrated oppositions. A dominant vertical posture is softened by rounded chair slats and sleeve rolls. A deep, near-monochrome robe is leavened by pale rails and cuffs. The small, warm focal area of the face is set within a wide, cool field of green. Scale is handled with care: large planes carry across the room, while minor incidents—the white collar’s notch, a scratch line in the robe—reward close viewing. These choices make the image legible at distance and inexhaustible up close.

The Viewer’s Path And The Experience Of Time

At first glance, we take in the sitter held in a world of green. On the second pass, the eye begins to notice micro-events: a pale bloom of mint that kisses the hairline; a rubbed passage that lets underpaint warm the robe; a doubled line at the right sleeve where the artist revised the contour; a cool blue-green seam that separates ear from background. With each circuit the painting yields more, turning from static portrait to a record of seeing and judging in real time. The experience of looking becomes an experience of calm duration.

Why The Work Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, the canvas holds its freshness because its modernity lies not in novelty of subject but in clarity of method. Pattern is minimal yet structural. Color is disciplined yet expressive. Drawing breathes within paint; light is democratic rather than theatrical. Designers learn from its limited palette and value control; painters study its living contour and economy; viewers appreciate a humane tempo that invites long looking. “Renée, Green Harmony” models how intensity can be won through restraint.

Conclusion: A Portrait Built From Air, Line, And A Single Color Family

“Renée, Green Harmony” distills Matisse’s Nice ideals into a lucid chord. A calm sitter, a chair that doubles as architecture, and a room tuned almost entirely to green yield an image of presence rather than pose. The portrait’s power rests on confident drawing, sensitive modulation, and an even light that lets color carry feeling. Everything necessary is here; nothing extra intrudes. The result is a portrait that breathes—quietly, persistently, and with unmistakable authority.